Related:

“Reducing the Cost of IP Law,” Mises Daily (Jan. 20, 2010) and Tabarrok’s Launching the Innovation Renaissance: Statism, not renaissance

Archived comments here, here, here, here, and reproduced below.

Reducing the Cost of IP Law

[This paper is the conclusion of a two-part series. The first article was “Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way.”]

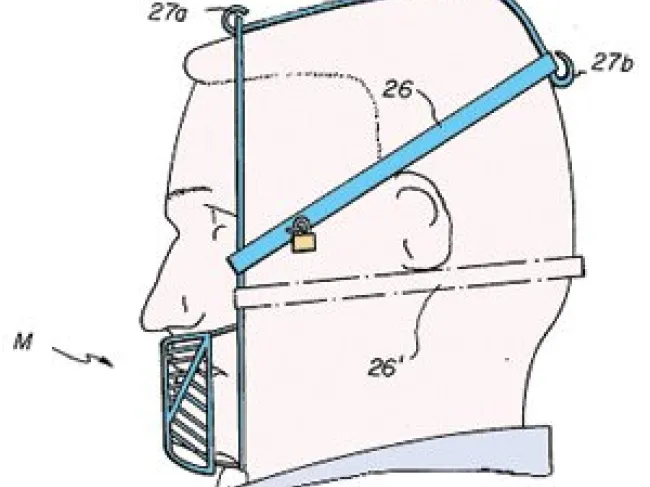

Anti-Eating Mouth Cage US Patent Issued in 1982

As I noted in Part 1, there is a growing clamor for reform of patent (and copyright) law, due to the increasingly obvious injustices resulting from these intellectual property (IP) laws.1 However, the various recent proposals for reform merely tinker with details and leave the essential features of the patent system intact. Patent scope, terms, and penalties would still be essentially the same.

How should the IP system be reformed? For those with a principled, libertarian view of property rights, it is obvious that patent and copyright laws are unjust and should be completely abolished.2 Total abolition is, however, exceedingly unlikely at present. Further, most people favor IP for less principled, utilitarian reasons. They take a wealth-maximization approach to policy making. They favor patent and copyright law because they believe that it generates net wealth — that the value of the innovation stimulated by IP law is significantly greater than the costs of these laws.3

What is striking is that this myth is widely believed even though the IP proponents can adduce no evidence in favor of this hypothesis. There are literally no studies clearly showing any net gains from IP.4 If anything, it appears that the patent system, for example, imposes a gigantic net cost on the economy (approximately $31 billion a year, in my estimate).5 In any case, even those who support IP on cost-benefit grounds have to acknowledge the costs of the system, and they should not oppose changes to IP law that significantly reduce these costs, so long as the change does not drastically reduce the innovation gains that IP purportedly stimulates. In other words, according to the reasoning of IP advocates, if weakening patent strength reduces costs more than it reduces gains, this results in a net gain.

In this paper I attempt to identify the most important changes that should be made to IP law to reduce its most egregious and significant costs, while not gutting its alleged innovation-stimulating effects. Keep in mind, however, that even the advocates of IP cannot show what its costs or alleged gains are; they provide no quantitative evidence but only intuition and qualitative reasoning. Thus, they cannot object if my suggestions also rely on common sense and extensive experience with the working of the existing IP system.

Moreover, given that virtually all empirical studies in this regard conclude that IP is either neutral or a net cost, the burden of proof should be on the IP advocate to show that a proposed change that clearly and significantly reduces costs should not be made. I will focus primarily on patent law, and also conclude more briefly with some proposed improvements to copyright and federal trademark law.

Costs and Benefits of IP Law

As noted above, the utilitarian or wealth-maximization arguments in favor of patent rights claim that a patent system is desirable because it does more good than harm — that it generates more wealth than it costs. The “wealth” purportedly generated is a result of the patent monopoly6 providing an incentive to innovate, and to disseminate knowledge that would otherwise be kept secret.

The idea is that, instead of keeping an invention as a trade secret, the inventor, in exchange for the limited monopoly on the invention, makes the information about it public in a published patent that others can learn from, even if they can’t yet use the patented device or process. And the promise of monopoly profits, or the reduction of free-rider effects, can incentivize innovation at the margins.7

But benefits are not enough. The standard argument for patents is that the system leads to a net benefit — that the benefits exceed the costs. While IP proponents may dispute the claim that a patent system produces no overall, unambiguous benefits to offset its costs (discussed further below), it cannot be denied that there are significant costs.

Note also that both costs and purported benefits are related to the “strength” of patent rights: the length of the patent term, the extent and type of penalties imposed on infringers, and the scope of patent rights. Stronger patents, according to the standard argument, will produce greater incentives to generate even more innovation-related wealth, but at increased cost. Conversely, weaker patents would impose fewer costs but would provide smaller incentives to disclose and innovate.

Patent proponents must, if only grudgingly, concede that diminishing returns are achieved at a certain point — that the “net” wealth produced by the patent system decreases as the marginal increase in costs exceeds the marginal increase in alleged benefits. Patent advocates, for example, do not advocate quintuple damages instead of treble damages, or capital punishment for willful infringement, or making the patent term 1,000 years, or increasing patent scope to include algorithms and abstract scientific discoveries. They implicitly believe that strengthening the patent system in this way would cost more than would be gained.

And yet patent advocates also resist reductions in patent strength, even though it is possible that the costs could fall more dramatically than the alleged benefits. Or, as one economist puts it, that we are “on the wrong side of the Laffer curve for innovation.”8

The costs of the patent system are widespread. Ridiculous patents are issued or filed and companies are enjoined from selling their products. Judgments are issued and settlements reached for billions of dollars.9

Untold hundreds of millions of dollars are spent annually on patent programs, largely for defensive purposes — to dissuade competitors from bringing a patent infringement lawsuit for fear of being hit with a similar counterclaim. Often, dominant competitors sue each other, and then back down, settling with a huge cross-license to each other’s patent portfolios. This gives them freedom to operate, but the threat to the smaller players remains.

Once again, as in the case of minimum-wage, social-security, and prounion laws, federal legislation works in favor of big business,10 and small companies or independent inventors are left out in the cold at the mercy of million-dollar patent suits filed by the business oligarchs. Or after one company prevails in a patent suit against a competitor, the wounded victim succumbs and is absorbed by the victor.11 Would that these millions of dollars could have been spent on salaries, R&D, equipment, or other capital investments instead, or simply been returned to shareholders in the form of dividends.

The possibility of being shut down by a competitor is a perennial threat to businesses, especially small companies, who cannot afford to spend millions of dollars defending a patent suit. High-tech startups are even more vulnerable: they often have very low cash or profits, making them even less able to defend a patent lawsuit; and because they use newer technology, they are also more likely to infringe patents. It is virtually impossible to be aware of all the patents that are out there, or that are about to emerge, or that have just been filed (and that are secret for 18 months after filing).

And even if one could identify all of the pertinent patents, there can be literally thousands of patent claims (the several defined inventions set forth in each patent that define the “metes and bounds” of protection granted by the patent) that could be a potential problem, and no definitive interpretation of any of them. Most claims have not been parsed by a court, and many are intentionally obscure or vague, having been drafted by highly skilled, crafty patent attorneys taking maximum advantage of ever-shifting, complex and arcane rules,12 and having been approved by understaffed government patent examiners unable to find all the relevant prior art.

And so companies do what they can but, in the end, they often just forge ahead, risking a patent suit (after all, a patent infringement lawsuit is not the only risk that entrepreneurs face), hoping not to be noticed, or hoping to be successful enough to accumulate the war chest needed to fight a patent suit or to have acquired enough of a patent arsenal to fight back or ward off such an attack in the first place. In some cases, no doubt, the nascent business is never formed; the would-be entrepreneur, sensing a dangerous patent thicket, steers clear of a given technology or business — thus leaving it to the techno-oligarchs (unseen costs are still costs, as Bastiat observed).13 Or a given company sticks to its current lines of business, afraid to venture into a heavily patented area. And so on. So much for innovation or entrepreneurial risk.

So the costs of the patent system are obvious and huge, if not easily quantifiable. Patent proponents themselves have no idea what the exact costs, or purported benefits, of the patent system are; they have no idea what the net benefit of the patent system is, or whether there even is a net benefit. We can identify some of the costs, but not all of them. It is, in any event, certain that there are tremendous costs to individuals, businesses, and the economy in general.14 As noted by Dell Inc., et al., in their amicus curiae brief to the Supreme Court in the Quanta Computer v. LG Electronics case,

[Patent] rights are intended to encourage innovation but come at a significant cost to other market participants and are “restrictive of a free economy” (United States v. Masonite Corp.… (1942)). Indeed, this Court recently recognized that when patent rights are not appropriately defined, “patents might stifle, rather than promote, the progress of useful arts.” KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc.… (2007). [emphasis added]

And as pointed out by Allison et al.,

Inventors come up with a new idea, hire a lawyer, write a patent application, spend years in the arcane and labyrinthine procedures of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO), get a patent, and then … nothing. Ninety-nine percent of patent owners never even bother to file suit to enforce their rights. They spend $4.33 billion per year to obtain patents, but no one seems to know exactly what happens to most of them. Call it “The Case of the Disappearing Patents.”15

One study suggests that American companies spend $11.4 billion a year on software patent litigation;16 another conservatively estimates that “the economic losses resulting from the grant of substandard patents can reach $21 billion per year by deterring valid research with an additional deadweight loss from litigation and administrative costs of $4.5 billion annually.”17 I have estimated the net cost of the American patent system to be at least $31 billion annually.18

Other costs include

- “In Terrorem Effects” (deterring potential competitors or follow-on innovators from entering a field by the existence of patents owned by their competitors)

- “Holdup Licensing” (patent owners might try to game the system by seeking to license even clearly bad patents for royalty payments small enough that licensees decide it is not worth going to court, likely costing in the hundreds of millions of dollars)

- “Facilitating Collusion” (licensees might agree to pay royalties on patents they know are invalid as part of a scheme to cartelize an industry)19

- Causing consumers to absorb monopoly prices over “inventions” that were already effectively common knowledge

- Directing resources away from productive research and instead toward strategic accumulation of patents already filed over innovations already deployed

- Diverting resources to “defensive patenting” or securing offensive “blocking patents”

- Directing research away from areas of existing patents that should not have been granted

- Directing resources toward acquiring and enforcing substandard patents and collecting royalties rather than other, more-productive fields of economic activity.20

Some argue that the patent system actually reduces net innovation — that the costs of the patent system are not only greater than its benefits, but that the patent system imposes costs and also reduces innovation.21 In other words, it is not only that the patent system imposes billions of dollars in costs, and that it is uncertain whether the extra innovation stimulated is worth more than this cost; it also seems likely that the patent system actually stifles and impedes innovation, adding injury to injury.

And this is just a smattering of the possible harms and costs of the patent system. If patent rights can be adjusted to significantly reduce these costs, without obviously reducing the benefits by a greater amount, then even utilitarian patent proponents should favor this change — unless they can demonstrate otherwise with sound reasoning or empirical data.

“Who can deny that, given the existing system, patent attorneys perform a valuable service? If we someday develop a cure for cancer, there will be no cancer doctors; this does not mean cancer specialists are not needed now, so long as there is cancer.”

Most natural-rights patent advocates, such as Ayn Rand, also oppose patent rights of infinite duration or scope. They do not believe patents should last forever, or that capital punishment should be imposed for infringement, for example. Instead, they favor some finite duration and scope for patent rights — 17 or so years of enforceability, and so on. Now, if these limits are arbitrary, the “principled” patent proponent has little basis to oppose moving patent boundaries in one direction or the other — a 12- or 28-year patent term is just as good (and as arbitrary) as a 17-year term.22 What inevitably happens is that the deontological or principled proponent of patent rights resorts to utilitarian standards to argue for drawing the line here as oppose to there. They, too, therefore, have no principled opposition to changes that significantly reduce the patent system’s costs.

As for patent skeptics and opponents, they, too, will endorse changes to the patent system that unambiguously reduce its costs. My proposals should find favor in the eyes of those who would like to abolish patents altogether. Someone who wants the patent term reduced from seventeen to zero years will be in favor of reducing the term to twelve years, for example. The proposals herein are thus analogous to arguing for a lower tax rate, no matter what type of tax is in place — as opposed to proposing tinkering with the tax system to make it more “fair” or efficient.23

So, it is uncontroversial that patents should not be “too easy” to get, nor should they be “too strong.” Even the Supreme Court, over a century ago, acknowledged that if patent monopolies are granted “for every trifling device, every shadow of a shade of an idea, which would naturally and spontaneously occur to any skilled mechanic or operator in the ordinary progress of manufactures,” then

such an indiscriminate creation of exclusive privileges tends rather to obstruct than to stimulate invention. It creates a class of speculative schemers who make it their business to watch the advancing wave of improvement, and gather its foam in the form of patented monopolies, which enable them to lay a heavy tax upon the industry of the country, without contributing anything to the real advancement of the arts. It embarrasses the honest pursuit of business with fears and apprehensions of concealed liens and unknown liabilities lawsuits and vexatious accountings for profits made in good faith.24

In other words, it’s a good thing if patent applicants face a high hurdle; if it’s difficult to obtain a patent, fewer patents on “trifling devices” will be granted.

The Silent Bar

Some patent attorneys balk at such critiques of the patent system. They take it personally, as if their career choice is under attack. But they should not. Who can deny that, given the existing system, patent attorneys perform a valuable service?25 By analogy, in a just society there would be no taxation, and thus no need for tax attorneys. But given the existence of taxation, tax attorneys provide a valuable service to there clients. If we someday develop a cure for cancer, there will be no cancer doctors; this does not mean cancer specialists are not needed now, so long as there is cancer. Nor are tax attorneys and oncologists expected to favor taxes or cancer.

Why, then, should patent attorneys be required to favor the current patent system as a policy matter, just because they are navigating the existing rules on behalf of their clients?26 The problem is not what patent attorneys do; it’s what they favor. Similarly, the problem with a protax tax attorney is not that he defends people from the IRS; it’s that he advocates a tax system. And everyone would object to a cancer doctor working to cause more people to have cancer.

And are my cynical views about patents really that isolated among the patent bar? Sure, most patent lawyers give lip service to the idea that patents are “necessary” to “promote innovation.” Yet almost none, in my experience, give any serious thought to this. Most, if they have any opinion at all, simply repeat the bromides they hear in law school and that courts and law professors repeat ad nauseum as if they are obvious, undisputed truths. Virtually all of them have been pickled in the wealth-maximization, law-and-economics ideas rife in law school. So they have a vague notion that the patent system is good because it encourages innovation. And innovation is a good thing, right? It adds value to the economy and improves our lives. Ceteris paribus, of course.

And there’s the rub — the ceteris paribus “gotcha.” Rarely do any patent advocates bother to ask whether the patent system’s costs are greater than its alleged benefits.27

Talk to a typical patent practitioner: he will almost unfailingly state his support for the patent system and “the inventor.” Innovation is good, he’ll say; so of course it should be protected, encouraged, and stimulated. But drill a bit deeper, ask him if he has any reasons for this other than what he has heard others say, and he’ll usually cave in, or change the subject. You quickly realize most of them just do not care. (It’s sort of like asking a public-school teacher why she favors public education. She claims to be in favor of it, but is not interested in coming up with a non-self-serving justification for it.)

For this reason, perhaps, almost none of them are even aware that no one seems to have ever established that the purported benefits of patents are greater than their costs. They do not know that whenever any attempt is made to estimate the costs of the patent system and to compare them to its benefits, the study is either inconclusive or concludes that the patent system is a net loss to the economy.28 They will reflexively repeat the standard propatent mantra if asked, but they really don’t care, or know, whether these purported justifications make any sense.

In a way, it is refreshing that patent attorneys do not care whether the patent system is really justifiable. Tax attorneys defend victims of a rapacious state without necessarily defending taxes — or even having an opinion about it. If you hire a tax attorney, you want an effective one, not one who has the right policy views.

Likewise with patent attorneys. They are a conservative lot — most are engineers in a former life — and don’t want to rock the boat. They don’t need to come out with a sophisticated stance on patent policy in order to represent clients. They don’t need to point out that the emperor has no clothes, or even figure this out in the first place. And clients really don’t care about this any more than they care whether their advocates read comics in private or what church they attend. It’s just not relevant.

Nevertheless, my experience would indicate that the propatent stance of the patent bar is not as uniform as surface appearances might indicate. To be sure, there are the expected, official, propatent comments by the “respectable,” establishment IP advocacy groups — the ABA, the AIPLA, Intellectual Property Owners Association, the various “IPLAs” — PIPLA, HIPLA, NYIPLA — and so on.

But if you press your average practitioner when the senior partner’s not listening, it’s not hard to get him to admit he’s just doing what he has to do to pay the mortgage. He doesn’t care about the system’s “legitimacy,” and doesn’t pretend to know much about it either, other than genuflecting when the IP priests tell him to. In fact, many display a refreshingly self-honest cynicism in this regard. It’s the kind of thing that many in the profession know but can’t say too loudly in polite company.

Take, for example, the results of this informal web poll I conducted a while back. The poll was circulated among both patent attorneys and libertarians (and others, such as Digg readers), in which 84 percent of respondents (at this writing) answered “Yes” to the question “Would you give up your right to sue others for patent infringement in exchange for immunity from all patent lawsuits?”

And consider the offhand comment in which a patent attorney admits, “Patents are intended to lure potential inventors into the business of innovation. The truth is, however, that very little is known about how patents really drive innovation.” Consider also a poignantly honest admission that was made by a patent attorney in an email to me in response to a letter in the trade magazine, IP Today.29 I had critiqued patent litigator Joseph Hosteny‘s defense of patent trolls — in particular his comment that “the patent system is necessary for there to be invention and innovation.” I had written,

There is … no conclusive evidence showing that the purported benefits of the patent system — extra innovation induced by the potential to profit from a patent; earlier-than-otherwise public disclosure of innovation — exceeds the significant and undeniable costs of the patent system.… Is the patent system “worth it”? Who knows? Apparently no one does. It seems to follow that we patent attorneys ought not pretend that we do.

In response I received an interesting email from a respected patent attorney, a senior partner in the IP department of a major national law firm who shall remain anonymous:

Stephan, Your letter responding to Joe Hosteny’s comments on Patent Trolls nicely states what I came to realize several years ago, namely, it is unclear that the U.S. Patent System, as currently implemented, necessarily benefits society as a whole. Certainly, it has benefited [Hosteny] and his [partners] and several of their prominent clients, and has put Marshall, Texas on the map; but you really have to wonder if the “tax” placed on industry by the System … is really worth it.30

It is my belief that there is at least tacit recognition by a nontrivial segment of the patent bar that they are participating in a scheme where wealth is transferred from “infringers” to “patentees,” with the patent practitioners extracting a healthy handling fee. They have no idea whether this system is “good for” the economy or society as a whole, nor do they care, despite giving lip service to the propatent yada yada.

This does not imply that companies can afford not to fight within the rules of the current system. They have to acquire patents if only for defensive reasons: to ward off patent infringement suits from competitors.

But the question at hand is what kind of changes ought to be made to improve the situation. Anything that can reduce the risks and costs faced by entrepreneurs and businesses ought to be given serious consideration. Most of all, market actors need freedom to operate — freedom to engage in business without fear of competitors using the power of the state to hobble them or shut them down.

Typical Proposals for Reform

Before laying out my own proposed changes, it is illuminating to note the reform proposals typically advanced. For example, James Bessen and Michael J. Meurer, in their book Patent Failure: How Judges, Bureaucrats, and Lawyers Put Innovators at Risk (Princeton, 2008), propose the following:

- “Make patent claims transparent.”

- “Make claims clear and unambiguous by enforcing strong limits against vague or overly abstract claims.”

- “Make patent search feasible by reducing the flood of patents.”

- “Besides improving notice, we also favor reforms to mitigate the harm caused by poor notice. These include an exemption from penalties when the infringing technology was independently invented and changes in patent remedies that might discourage opportunistic lawsuits.”

The group Public Knowledge proposes the following reforms to improve patent law and the patent-litigation process:

- Raising the standard from determination of obviousness from the person having “ordinary skill” in the art to a person having “recognized skill” in the art.

- Peer review of patent applications.

- Permitting third parties to submit prior art, and rewarding them with fee reimbursement if successful.

- Permitting post-grant review of patents by the USPTO prior to litigation.…

- Removing the presumption of validity that issued patents enjoy.

- Apportioning damages to be proportional to the value of the patent.

- Allowing circuit courts other than the Federal Circuit to hear patent appeals.

- Limiting litigation venues to those jurisdictions with a meaningful connection to one of the litigants.

Other proposals for reform abound.31

While some of these ideas would no doubt improve matters, most of them are at best minor, mere tinkering with the system. Making patent claims more “transparent” is a technical, elusive goal that still will not reduce the term or scope of patents, or the penalties imposed for infringement, for example. Of these suggestions, providing an independent inventor defense is best.

Proposed Improvements to Patent Law

Below are suggested reforms to the existing patent system that would, in my view, significantly reduce the costs and harm imposed by the patent system while not appreciably, or as significantly, reducing the innovation incentives and other purported benefits of the patent system. The changes proposed below are changes I believe would benefit high-tech companies as well as other companies that do not develop a great deal of patentable technology. I list these changes in generally descending order of importance.

Reduce the Patent Term

Companies face an immense patent thicket. In part this is due to the approximately 17-year patent term. It is not uncommon to come across patents issued 10 or 15 years earlier that pose a threat to one’s business. Many of these patents should not have been issued. Appeals for “improving patent quality” are likely to be futile or of minimal effect, as are the calls for improving government “efficiency” by presidential candidates every four years.

“This does not imply that companies can afford not to fight within the rules of the current system. They have to acquire patents if only for defensive reasons. But the question at hand is what kind of changes ought to be made to improve the situation.”

The patent term should be reduced to 5 or 7 years (from approximately 17–18 years now). (Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos actually proposes a 3–5 year term for business method and software patents.)32 Such a reduction would eliminate a huge portion of the patent threat that entrepreneurs and companies face, drastically reducing the costs borne by companies. There would be fewer lawsuits and fewer threats, lower insurance premiums, and reduced patent license fees and royalties. (Note: it is true that products such as pharmaceuticals and medical devices may be delayed for years by the FDA approval process. However, at least some of the time lost can be added to the patent term, so that such products would still have a patent coverage period once the product receives regulatory approval.)

Yet there would still be an incentive to file patent applications to obtain a 5–7 year monopoly on one’s idea. Would the incentive be reduced somewhat? Probably. But there is no reason to think the incentive would be drastically reduced, or that we would lose more marginal innovation and disclosure than would be saved.

Another twist would be to have a sliding scale, with longer terms granted for different types of subject matter (e.g., business methods, software, and pharmaceuticals). Such an approach would, obviously, be more complex and probably hopelessly unworkable. (See also the discussion of a petty patent system, below.)

Remove Patent Injunctions/Provide Compulsory Royalties

Paying royalties is one thing. This is similar to a tax. It impedes and puts a drag on efficiency. Worse still is the prospect of an injunction, which can simply shut a company down. Quite often this is what a competitor will seek. They do not want damages or money: they want to dominate the market and eliminate competition. Or the threat of injunction is used to basically wring money from an alleged infringer (e.g., the $600 million RIM (BlackBerry) had to pay, even though the patents were under appeal at the PTO, due to the threat of an injunction).

If the purpose of the patent system is to provide some incentive to innovators, then receiving a monetary payment should be sufficient. Patent injunctions should be abolished entirely. The only remedy should be an award of damages (for past infringement) or a compulsory license (ongoing royalties based on future “infringement”).

This would prevent patentees from shutting down competitors. At most, they could impose a small “tax.” Litigation costs, insurance premiums, and the ability of patentees to extract unreasonable royalties from alleged infringers would be radically curtailed. On the other hand, because patentees would still be able to seek reasonable royalties, there would still remain a substantial incentive to file for patents.

The compulsory licensing approach is not new. Some countries impose compulsory licensing on patentees who do not adequately “work” the patent.33 The United States already provides for compulsory licensing in certain cases, as the US government threatened to do in the Cipro anthrax drug case.34 Also, in the wake of the recent eBay case, some courts are awarding some form of ongoing royalty of compulsory license instead of an injunction. 35

Royalty Cap/Safe Harbor

A variation of this approach would be to set a cap on the total amount of royalties that any one company would have to pay for compulsory patent royalties (at least, for a given product) — for example, 5 percent. Thus, if one is sued by 3 different patentees, at most he has to pay 5 percent royalties on sales. If too many patent vultures hound an innocent businessman, he could simply throw his hands up, deposit his 5 percent royalty with some escrow agent and let them fight it out.

Update: Limit patent owners to suing only one victim

From Dave Jones, Executive Director of the High Tech Inventors Alliance: (( Industry Opposition to Patent Challenges. ))

So, tell you what, Brian, I’ll trade you one and done on the IPR side for one and done on the litigation side. Patent owners can only bring one case, preferably just against one defendant and then they’re done forever. And they can’t sue anybody. And then we can have one and done on the IPR side. I’d be happy to make that deal.

Reduce the Scope of Patentable Subject Matter

Currently, patents can be obtained for a wide array of inventions: pharmaceuticals, and any type of “useful” apparatus or method, including software and business methods. This is due to the broad wording of Section 101 of the US Patent Act,![]() which has been construed to mean that the “statutory subject matter” includes “anything under the sun that is made by man.”

which has been construed to mean that the “statutory subject matter” includes “anything under the sun that is made by man.”

Copyright already covers software. It should be excluded from the scope of patentable subject matter. Ditto “business methods.” (Business and software patents are relatively new anyway, so that excluding them from the scope of patentable subject matter is only rolling the clock back a decade or two.) In fact, the example most often given to show that patents are needed is pharmaceuticals. So, let’s eliminate patents for everything except pharmaceutical compounds — and reduce the term to 3–5 years. For a spoonful of sugar to help the medicine go down, the FDA should be abolished, and federal and state taxes and regulations eased.36

Provide for Prior-Use and Independent-Inventor Defenses

Under copyright law, someone who independently creates an original work similar to another author’s original work is not liable for copyright infringement, since the independent creation is not a reproduction of the other author’s work. Thus, as a defense a copyright defendant can try to show he never had access to the other’s work.

Patents, however, are different. As long as someone is an actual inventor of an invention (he did not learn about it from someone else), and the invention was not publicly known, he can obtain a patent for it. Someone who previously invented the same thing and is using the idea in secret can actually be liable for infringing the patent granted to the second inventor. Also, if a later person independently invents the same idea that was previously patented by another, this is also no defense. Prior use, or independent invention, is not a general defense. There is currently only a very limited “prior user” right (or “first inventor defense”), available to those who commercially used a “business method” before someone else patented it. 37

A defense should be provided for those who are prior users of, or who independently invent, an invention patented by someone else. This would greatly reduce the cost of the patent system since one difficulty faced by companies is that they do not know what patents they might infringe. If someone learns of an invention from another’s patent, at least they are aware of the risk and can possibly approach the patentee for a license.

But quite often a company independently comes up with various designs and processes while developing a product, which designs and processes had been previously patented by someone else. If the goal of patent law is to reward invention, it should be sufficient to permit patentees to sue people who actually learned of the idea from the patent — just as copyright infringement exists when someone reproduced another’s work but not when it is independently created.

One patent-reform bill originally proposed to broaden the existing prior-user defense by eliminating the business-method patent limitation so that users of all types of inventions would have been able to use the defense, but this was removed from later versions of the bill. A broad prior-user defense should be established, as well as an independent-inventor defense that even a later inventor could use. 38

Instantly Publish All Patent Applications

Until 1999, patent applications remained secret until they issued. Thus arose the problem of “submarine patents“: patents could remain pending in secret for decades — after industry had independently invented and widely adopted the technology — and then “emerge” like a submarine and extract heavy royalties from many companies. The 1995 amendments to patent law changed the patent term from 17 years from date issuance, to 20 years from the date of filing, to reduce this problem. And starting in 1999, US patent applications are now made public 18 months after filing, unless the applicant requests nonpublication and promises not to file the patent internationally.

Part of the “patent bargain” is that the state grants a limited monopoly to inventors in exchange for public disclosure of the invention. This is why patents are published. The publication of (most) patent applications at 18 months was an improvement, but should be changed to mandatory, instant publishing of all patent applications (with perhaps a minor delay for any national-security or foreign-filing-license clearance). This would help potential patent defendants by giving them more opportunity to be aware of potential patent threats a year and a half earlier. Patent applicants have to reveal their secrets at 18 months anyway, and are the ones requesting a state monopoly to use to sue people, so they have no grounds to complain about having to give a bit more fair notice to their potential victims.

Eliminate or Restrict Enhanced Damages

Under current law, if the patentee can prove the infringer “willfully” infringed, up to treble damages can be obtained. This is punitive. The patentee ought to be able to recover only actual damages, not three times that amount.39

Working/Reduction to Practice Requirement

Under current law, there is no requirement that an invention be actually reduced to practice before a patent is granted on it, or that it be “worked” after grant to maintain the patent in force. When a patent application is filed, this is considered to be a “constructive reduction to practice.” It would make it more difficult to obtain frivolous patents if the inventor had to make an actual, working model of the invention — and if the patented invention had to be actually worked or used by the patentee to stay in force.1

Provide for Advisory Opinion Panels

Under our current patent system, if a company becomes aware of patent that might be a problem, or is accused of infringing the patent, the company has only limited choices. It can ignore it, risking possible treble damages for willful infringement; it can try to negotiate a possibly expensive license, even though the patent’s claims may be ambiguous or its validity doubtful; or it can pay $30,000 or more for a patent opinion that may not do much good anyway.

A cheaper, more streamlined option ought to be introduced to permit a more authoritative opinion to be obtained that helps nail down the scope of the patent’s claims and whether or not the patent is valid. The UK introduced such a service a couple of years ago. Variations of this approach could be employed; as noted above, Public Knowledge proposes “peer review of patent applications,” “permitting third parties to submit prior art, and rewarding them with fee reimbursement if successful,” and “permitting post-grant review of patents by the USPTO prior to litigation.”

Losing Patentee Pays

In the US system, a victorious defendant in a patent-infringement lawsuit usually still pays for his legal defense, which may run in the millions of dollars. The system should be changed so that a patentee who loses an infringement suit must pay the defendant’s legal and other costs. The IPO recently proposed a loser-pays approach, but in my view, the defendant should never have to pay the fees of the patentee, since the defendant did not instigate the suit.

Expand Right to Seek Declaratory Judgments

Under current law, someone threatened with a patent lawsuit can bring a declaratory judgment (DJ) action to have a court decide the issue. The MedImmune decision made it easier for licensees to use a DJ action to challenge the validity of patents they had previously licensed. The Declaratory Judgment Act should be expanded to make it easier for potential infringers to bring an action against a patentee if there is any doubt by the potential infringer.

For example, if A is worried about violating B’s patent, A could request B to provide a written exoneration statement that it does not intend to sue A or request a license for a given product. If B does this, B is estopped from ever suing A for patent infringement with respect to that product. If B refuses to provide the statement within 30 days, then A has a right to seek a DJ. Better yet — A provides B a description of its product and demands an exoneration statement; if B does not provide one, it releases its right to sue A. This would give B 30 days to decide whether to admit to A that it intends to sue. If B makes this admission, this triggers A’s right to seek a DJ.

Exclude IP from Trade Negotiations

The United States routinely uses its international heft to coerce other states into adopting more draconian IP laws. This increases costs internationally for American and other companies.40

Other Changes

There are a host of changes that have been proposed. These include changing from a first-to-file to a first-to-invent system; reducing the scope of patent claims; 41 increasing PTO funding to “improve” the examination process; refining the criteria for injunctions to be granted; permitting postgrant challenge of patents or submission of prior art by third parties; implementing a “peer-to-patent” review system; and establishing a federal office to review PTO actions.42 Some have suggested adopting a utility model or “petty patent” system, in which patent applications are examined only minimally and receive narrower protection; this type of IP right is already available in some countries. 43 Many of these proposals are aimed at “improving patent quality” or other dubious goals. These changes are, by and large, of either doubtful or trivial value.

Nevertheless, some fairly minor or technical, but largely positive, changes could also be made, which I list only briefly here:

- Increase the threshold for obtaining a patent 44

- Increase patent filing fees to make it more difficult to obtain a patent

- Make it easier to challenge a patent’s validity at all stages

- Require patent applicants to specify exactly what part of their claimed invention is new and what part is “old” (e.g., by the use of European-style “characterized in that “claims)

- Require patent applicants to do a search and provide an analysis showing why their claimed invention is new and nonobvious (patent attorneys really hate this one)

- Limit the number of claims

- Limit the number of continuation applications

- Remove the presumption of validity that issued patents enjoy

- Apportion damages to be proportional to the value of the patent

Copyright and Trademark

Of course, patent law is not the only area of IP law that could stand improvement. Examples of copyright45 and trademark46 abuse also abound. I will not discuss these matters in depth here, other than to briefly suggest a few proposals for reform.

Copyright

- Radically reduce the term, from life plus 70 years to, say, 10 years

- Remove software from copyright coverage (it’s functional, not expressive)

- Require active registration and periodic re-registration (for a modest fee) and copyright notice to maintain copyright (today it is automatic, and it is often impossible to determine, much less locate, the owner), or otherwise make it easier to use “orphaned works“47

- Provide an easy way to dedicate works to the public domain — to abandon the copyright the state grants authors48

- Eliminate manifestly unjust provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), such as its criminalization of technology that can be used to circumvent digital protection systems

- Expand the “fair use“ defense and clarify it to remove ambiguity49

- Provide that incidental use (e.g., buildings or sculptures appearing in the background of films) is fair use

- Reduce statutory damages50

Trademark

- Raise the bar for proving “consumer confusion”

- Abolish “antidilution” protection

- In fact, abolish the entire federal trademark law, as it is unconstitutional (the Constitution authorizes Congress to enact copyright and patent laws, but not trademark law)

* * * * *

This paper is the conclusion of a two-part series. The first article was “Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way.”

- 1Kinsella, Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way, Mises Daily (Oct. 1, 2009).

- 2See Kinsella, The Case Against IP: A Concise Guide, Mises Daily (Sept. 4, 2009).

- 3Kinsella, There’s No Such Thing As a Free Patent, Mises Daily (Mar. 7, 2005).

- 4Kinsella, Yet Another Study Finds Patents Do Not Encourage Innovation, Mises Blog (July 2, 2009).

- 5Kinsella, What Are the Costs of the Patent System?Mises Blog (Sep. 27, 2007).

- 6See Kinsella, Are Patents “Monopolies”?Mises Blog (July 13, 2009).

- 7See Kinsella, There’s No Such Thing as a Free Patent; Corinne Langinier & GianCarlo Moschini, “The Economics of Patents: An Overview,” Working Paper 02-WP 293, Center for Agricultural and Rural Development, Iowa State University (2002) (discussing benefits and costs of patents, including “patents can promote new discoveries” and “patents can help the dissemination of knowledge”).

- 8See Kinsella, “Libertarian Favors $80 Billion Annual Tax-Funded ‘Medical Innovation Prize Fund’” Mises Blog (Aug. 12, 2008). [What’s Worse: $80 Billion or $30 Million?; $30 Billion Taxfunded Innovation Contracts: The “Progressive-Libertarian” Solution]

- 9See “Appendix: Examples of Outrageous Patents and Judgments,” in Kinsella, Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way.

- 10For a recent example, UPS is currently lobbying Congress to enact legislation that would redefine its rival, FedEx, as a trucking company rather than the airline it started out as in an attempt to make it easier for the Teamsters union to unionize FedEx drivers and raise their wage rates—and of course FedEx’s cost structure. See Del Quentin Wilber & Jeffrey H. Birnbaum, Taking the Hill By Air and Ground: Shift in Congress Favors Labor, UPS Over FedEx, Washington Post (September 14, 2007). See also Murray N. Rothbard, Origins of the Welfare State in America, Mises.org (1996) (”Big businesses, who were already voluntarily providing costly old-age pensions to their employees, could use the federal government to force their small-business competitors into paying for similar, costly, programs…. [T]he legislation deliberately penalizes the lower cost, ‘unprogressive,’ employer, and cripples him by artificially raising his costs compared to the larger employer.… It is no wonder, then, that the bigger businesses almost all backed the Social Security scheme to the hilt, while it was attacked by such associations of small business as the National Metal Trades Association, the Illinois Manufacturing Association, and the National Association of Manufacturers. By 1939, only 17 percent of American businesses favored repeal of the Social Security Act, while not one big business firm supported repeal.… Big business, indeed, collaborated enthusiastically with social security.”); Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., “The Economics Of Discrimination,” in Speaking of Liberty (2003), at 99 (”One way the ADA [Americans with Disabilities Act] is enforced is through the use of government and private ‘testers.’ These actors, who will want to find all the “discrimination” they can, terrify small businesses. The smaller the business, the more ADA hurts. That’s partly why big business supported it. How nice to have the government clobber your up-and-coming competition.”); Rothbard, For A New Liberty (2002), pp. 316 et seq.; Rothbard, The Betrayal of the American Right, 185-86 (2007) (”This is the general view on the Right; in the remarkable phrase of Ayn Rand, Big Business is ‘America’s most persecuted minority.’ Persecuted minority, indeed! To be sure, there were charges aplenty against Big Business and its intimate connections with Big Government in the old McCormick Chicago Tribune and especially in the writings of Albert Jay Nock; but it took the Williams-Kolko analysis, and particularly the detailed investigation by Kolko, to portray the true anatomy and physiology of the America scene. As Kolko pointed out, all the various measures of federal regulation and welfare statism, beginning in the Progressive period, that Left and Right alike have always believed to be a mass movement against Big Business, are not only backed to the hilt by Big Business at the present time, but were originated by it for the very purpose of shifting from a free market to a cartelized economy. Under the guise of regulations “against monopoly” and “for the public welfare,” Big Business has succeeded in granting itself cartels and privileges through the use of government.”); Albert Jay Nock, quoted in Rothbard, The Betrayal of the American Right, 22 (2007) (”The simple truth is that our businessmen do not want a government that will let business alone. They want a government they can use. Offer them one made on Spencer’s model, and they would see the country blow up before they would accept it.”). See also Timothy P. Carney, The Big Ripoff: How Big Business and Big Government Steal Your Money (2006).

- 11See, e.g., Transocean v. GlobalSantaFe (S.D. Tex. Dec. 27, 2006) (permanent injunction granted in favor of plaintiff leads to acquisition of defendant by plaintiff).

- 12As the US Supreme Court has noted, “[t]he specification and claims of a patent… constitute one of the most difficult legal instruments to draw with accuracy ….” Topliff v. Topliff (1892). While this would appear to be a compliment to the skills of patent practitioners, it is really a testament to the inherent subjectivity and ambiguity in patent law (and a bit of a commentary on the technical illiteracy of most attorneys — they’re a bit overimpressed with engineer-attorneys: after all, they can actually do basic algebra!).

- 13See Frederic Bastiat, “That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen“ (1850); also Jeff Tucker, Seen and Unseen Costs of Patents, Mises Blog (Jan. 29, 2009).

- 14The US Constitution, Art. I, § 8, is based on such reasoning, in granting Congress the power “To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” As for costs, see note 29, above, and the references collected in the section “Studies on the Costs of the Patent System” in Kinsella, Revisiting Some Problems With Patents, Mises Blog (Aug. 2, 2007); Ronald Bailey, The Tragedy of the Anticommons: Do patents actually impede innovation?, Reason (Oct. 2, 2007); An Open Letter From Jeff Bezos On The Subject Of Patents (March 2000); “The Parade of Horribles” section of “Peer to Patent”: Collective Intelligence and Intellectual Property Reform. See also Robert P. Merges & Richard R. Nelson, “On the Complex Economics of Patent Scope,” 90 Colum. L. Rev. 839 (1990); Edmund W. Kitch, “The Nature and Function of the Patent System,” 20 J.L. & Econ. 265 (1977); Mark Lemley, “The Economics of Improvement in Intellectual Property Law,” 75 Tex. L. Rev. 989, 1044–1051 (1997); Barnett, Cultivating the Genetic Commons.

- 15John R. Allison, Mark A. Lemley, Kimberly A. Moore, R. Derek Trunkey, Valuable Patents. See also Mark A. Lemley, Rational Ignorance at the Patent Office, 95 Northwestern U. L. Rev. (2001).

- 16“End Software Patents” Launches With Website and Report, The 271 Patent Blog (Feb. 28, 2008).

- 17George S. Ford et al., Quantifying the Cost of Substandard Patents: Some Preliminary Evidence, Phoenix Center Policy Paper Number 30 (Sept. 2007) (”These estimates may be viewed as conservative because they do not take into account other economic costs from our existing patent system, such as the consumer welfare losses from granting monopoly rents to patent holders that have not, in the end, invented a novel product, or the full social value of the innovations lost.”); see also The cost of substandard patents, Technological Innovation and Intellectual Property blog (Feb. 21, 2008) and How Much Harm Do Bad Patents Do To The Economy?, Techdirt (Feb. 25, 2008).

- 18Kinsella, What are the Costs of the Patent System?.

- 19Mark A. Lemley, Rational Ignorance at the Patent Office, 95 Northwestern U. L. Rev. (2001).

- 20See The Cost of Substandard Patents.

- 21See Kinsella, Patents and Innovation, Mises Blog (Mar. 7, 2008), Revisiting Some Problems with Patents, and What Are the Costs of the Patent System?

- 22To be clear: the US patent term, prior to amendments to the Patent Act in 1995, was 17 years from the date the patent issued. After 1995, patents are enforceable after they are issued, until 20 years from the date the application was filed. Since patents typically take two or three years to issue, the effective term of patents is still about 17 years. See also C. Michael White, “Why a Seventeen Year Patent,” 38 J. Pat. Off. Soc’y 839 (1956) (describing historical basis for seventeen-year term and proposing shortened terms).

- 23On this see Llewellyn H. Rockwell, Jr., The Tax Reform Racket, observing that “The only tax plan anyone should trust is the most simple possible: the one that proposes to lower existing taxes.” See also Rockwell, Diversions; Rothbard, The Consumption Tax: A Critique, Power and Market, and The Myth of Neutral Taxation; Laurence Vance, The Fair Tax Fraud and Flat Tax Folly.

- 24Atlantic Works v. Brady, 107 US 192, 200 (1882).

- 25See Kinsella, Patent Lawyers Who Don’t Toe the Line Should Be Punished!Mises Blog (Sep. 29, 2009); idem, An Anti-Patent Patent Attorney? Oh my Gawd!StephanKinsella.com (July 12, 2009.

- 26See Mike Masnick, Is It So Crazy For A Patent Attorney To Think Patents Harm Innovation?, Techdirt (Oct. 1, 2009) (discussed here).

- 27See Kinsella, There’s No Such Thing as a Free Patent.

- 28See Kinsella, Yet Another Study Finds Patents Do Not Encourage Innovation; idem, Revisiting Some Problems With Patents; Barnett, Cultivating the Genetic Commons, p. 1008 (”There is little determinative empirical evidence to settle theoretical speculation over the optimal scope and duration of patent protection.”) (citing D.J. Wright, “Optimal patent breadth and length with costly imitation,” 17 Intl. J. Industrial Org. 419, 426 (1999)); Merges & Nelson, “On the Complex Economics of Patent Scope,” pp. 868-70 (stating that most economic models of patent scope and duration focus on the relation between breadth, duration, and incentives to innovate, without giving serious consideration to the social costs of greater duration and breadth in the form of retarded subsequent improvement)); Tom W. Bell, Prediction Markets for Promoting the Progress of Science and the Useful Arts, 14 G. Mason L. Rev. (2006):

“But [patents and copyrights] for the most part stimulate only superficial research in, and development of, the sciences and useful arts; copyrights and patents largely fail to inspire fundamental progress.… Patents and copyrights promote the progress of the sciences and useful arts only imperfectly. In particular, those statutory inventions do relatively little to promote fundamental research and development ….”And see Thomas F. Cotter, “Introduction to IP Symposium,” 14 Fla. J. Int’l L. 147, 149 (2002) (”Empirical studies fail to provide a firm answer to the question of how much of an incentive [to invent] is necessary or, more generally, how the benefits of patent protection compare to the costs.”); Mark A. Lemley, Rational Ignorance at the Patent Office, 95 Northwestern U. L. Rev. (2001), at p. 20 & n. 74:“The patent system intentionally restricts competition in certain technologies to encourage innovation. Doing so imposes a social cost, though the judgment of the patent system is that this cost is outweighed by the benefit to innovation.… There is a great deal of literature attempting to assess whether that judgment is accurate or not, usually without success. George Priest complained years ago that there was virtually no useful economic evidence addressing the impact of intellectual property.… Fritz Machlup told Congress that economists had essentially no useful conclusions to draw on the nature of the patent system.”See further Julie Turner, Note, “The Nonmanufacturing Patent Owner: Toward a Theory of Efficient Infringement,” 86 Cal. L. Rev. 179, 186-89 (1998) (Turner is dubious about the efficacy of the patent system as a means of inducing invention, and would argue against having a patent system if this were its only justification); F.A. Hayek, The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (U. Chicago Press, 1989), p. 36:“The difference between [copyrights and patents] and other kinds of property rights is this: while ownership of material goods guides the use of scarce means to their most important uses, in the case of immaterial goods such as literary productions and technological inventions the ability to produce them is also limited, yet once they have come into existence, they can be indefinitely multiplied and can be made scarce only by law in order to create an inducement to produce such ideas. Yet it is not obvious that such forced scarcity is the most effective way to stimulate the human creative process. I doubt whether there exists a single great work of literature which we would not possess had the author been unable to obtain an exclusive copyright for it; it seems to me that the case for copyright must rest almost entirely on the circumstance that such exceedingly useful works as encyclopedias, dictionaries, textbooks, and other works of reference could not be produced if, once they existed, they could freely be reproduced.… Similarly, recurrent re-examinations of the problem have not demonstrated that the obtainability of patents of invention actually enhances the flow of new technical knowledge rather than leading to wasteful concentration of research on problems whose solution in the near future can be foreseen and where, in consequence of the law, anyone who hits upon a solution a moment before the next gains the right to its exclusive use for a prolonged period. [citing Fritz Machlup, The Production and Distribution of Knowledge (1962)]”See also Kinsella, Patents and Innovation (noting economic historian Eric Schiff’s conclusion that when the Netherlands and Switzerland temporarily abolished their patent systems, they experienced increased innovation; Petra Moser’s finding that countries without patent systems innovate just as much, if not more, than those with patent systems). - 29Elaboration in Kinsella, Miracle — An Honest Patent Attorney!Mises Blog (Sep. 7, 2006). It could be argued not only that the costs of the patent system are greater than its innovation-advancing benefits — but that it actually impedes innovation, so that a cost is being incurred to actually stifle innovation. See, e.g., Ronald Bailey, The Tragedy of the Anticommons: Do patents actually impede innovation?, Reason (Oct. 2, 2007); Barnett, Cultivating the Genetic Commons:

“Broadly defined patents appear likely to exacerbate considerably the accessibility costs that attend any system of property rights. Extending any form of patent protection to biotechnological innovations obviously increases development costs for subsequent researchers and, depending on patent scope and duration, may reduce or eliminate some researchers’ incentives to improve upon existing innovations. This danger grows as patent size increases. If broad patents sufficiently inflate subsequent improvers’ accessibility costs, patent protection would fail a net social benefit test, since it would reduce the total stream of innovative output that exists in a world without any patent protection at all.” - 30Our anonymous correspondent continues:

“Of course, anyone can point to a few start-up companies that, arguably, owe their successes to their patent portfolios; but over the last 35 years, I have observed what would appear to be an ever increasing number of meritless patents, issued by an understaffed and talent-challenged PTO examining group, being used to extract tribute from whole industries. I have had this discussion with a number of clients, including Asian clients, who have been forced to accept our Patent System and the “taxes” it imposes on them as the cost of doing business in the USA. I wish I had the “answer”. I don’t. But going to real opposition proceedings, special patent courts with trained patent judges, “loser pays attorney fees” trials, retired engineers/scientists or other experienced engineers/scientists being used to examine applications in their fields of expertise by telecommuting from their homes or local offices throughout the Country, litigating patent attorneys providing regular lectures to the PTO examiners on problems encountered in patent infringement cases due to ineffective or careless examination of patent applications, and the appointment of actually qualified patent judges to the CAFC, may be steps in the right direction.”See Kinsella, Miracle — An Honest Patent Attorney! - 31See e.g., the Council on Foreign Relations study, “Reforming the U.S. Patent System: Getting the Incentives Right,” at p. 33; the Innovation Alliance’s suggestions for patent reform; Patent Reform Act of 2009, Patently-O (March 3, 2009); Patent Reform 2009: Reactionary Causes, Patent Baristas (March 3, 2009); also note 2 to Kinsella, Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way.

- 32An Open Letter From Jeff Bezos On The Subject Of Patents (March 2000). See also C. Michael White, “Why a Seventeen Year Patent,” 38 J. Pat. Off. Soc’y 839 (1956) (describing historical basis for seventeen-year term and proposing shortened terms); Barnett, Cultivating the Genetic Commons (”There is little determinative empirical evidence to settle theoretical speculation over the optimal scope and duration of patent protection.”) (citing D.J. Wright, “Optimal patent breadth and length with costly imitation,” 17 Intl. J. Industrial Org. 419, 426 (1999); Merges & Nelson, “On the Complex Economics of Patent Scope,” pp. 868–870 (stating that most economic models of patent scope and duration focus on the relation between breadth, duration, and incentives to innovate, without giving serious consideration to the social costs of greater duration and breadth in the form of retarded subsequent improvement)).

- 33See, e.g., Mexico-Selected Compulsory Licensing, Government Use, and Notable Patent Exception Provisions — Mexico Industrial Property Law. In accordance with article 5.A.2 and 4 of the Paris Convention, the French Patent Law (Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle) provides five different reasons for compulsory licensing, including “Non working of invention during four years from filing” (see L. 613-11 to 14). See also similar provisions in Sections 13, 24 and 81 of the German Patent Law. English translations of many foreign laws may be found in WIPO’s Collection of Laws for Electronic Access.

- 34See Ciprofloxacin: the Dispute over Compulsory Licenses; Tom Jacobs, Bayer, U.S. Deal on Anthrax Drug, Motley Fool (Oct. 25, 2001). See also Kinsella, Brazil and Compulsory Licenses, Mises Blog (June 8, 2007); Kinsella, Condemning Patents, Mises Blog (Feb. 27, 2005).

- 35See cases cited in note 15 to “Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way.” See also Peter S. Menell, “Intellectual Property and the Property Rights Movement,” Regulation (Fall 2007) (arguing that patent rights are unlike property rights and should not automatically receive the same protections as real property rights do, such as injunctions, exclusivity, and inviolability); Julie Turner, Note, “The Nonmanufacturing Patent Owner: Toward a Theory of Efficient Infringement,” 86 Cal. L. Rev. 179, 186–89 (1998), arguing that“the patent system should not benefit those who would use a patent solely as a barrier to entry, without intent to pursue commercialization of the underlying technology — entities which I will call “nonmanufacturing patent owners.” While disclosure may have value, mere disclosure fails to justify the granting of a monopoly absent the patent owner’s intent to commercialize the disclosed invention. As a result, the patent enforcement system should adopt a scheme whereby nonmanufacturing patent owners receive monetary relief equivalent to the “disclosure value” of their patents.”For more discussion of this issue, see Merges & Nelson, “On the Complex Economics of Patent Scope,” at notes 6–7 and accompanying text (”All in all, the substantial amount of evidence now available suggests that compulsory patent licensing, judiciously confined to cases in which patent-based monopoly power has been abused … would have little or no adverse impact on the rate of technological progress ….”) (quoting F.M. Scherer, Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance 456–57 (2d ed. 1980)). [For more on compulsory licensing, see Hickey, Kevin J.; Ward, Erin H., “The Role of Patents and Regulatory Exclusivities in Drug Pricing” (01/30/2024).]

- 36See Kinsella, Snarky IP Comment, StephanKinsella.com (Sep. 5, 2009) (”Hey, I know — let’s trust the same government that imposes FDA costs, taxes, and regulatory roadblocks to set up a patent office to hand out patents to give you partial ownership of others’ property to incentivize you just enough to overcome the costs they imposed on you on the first place with the FDA and taxes and regulations. Beautiful! And if that’s not ‘enough’ incentive, establish a government panel of ‘experts’ to give you ‘enough’ of a reward paid by taxpayers. Beautiful! I like it!”).

- 3735 USC § 273.

- 38See Kinsella, Common Misconceptions about Plagiarism and Patents: A Call for an Independent Inventor Defense, Mises Blog (Nov. 21, 2009). The CFR study “Reforming the U.S. Patent System: Getting the Incentives Right“ recommends a prior-user right be adopted; Bessen & Meurer, in Patent Failure, recommend an independent inventor defense.

- 39The CFR study “Reforming the U.S. Patent System: Getting the Incentives Right“ recommends making it more difficult to find willful infringement.

- 40See Kinsella, IP Imperialism (Russia, Intellectual Property, and the WTO), Mises Blog (Sept. 22, 2006); idem, China, India like US Patent Reform, Mises Blog (Dec. 10, 2007).

- 41See Merges & Nelson, “On the Complex Economics of Patent Scope“ (arguing that excessively broad patents can impede progress and hinder or block subsequent innovation, especially in science-based industries). See also Julie E. Cohen & Mark A. Lemley, Patent Scope and Innovation in the Software Industry, Cal. L. Rev. (2001); Barnett, Cultivating the Genetic Commons (quoted in note 29 above).

- 42See Peer-to-Patent Review system, Patent Baristas (Oct. 1, 2007); PatentFizz.com (allows public comments on patents). See also the proposals of Public Knowledge proposes “Peer review of patent applications,” “Permitting third parties to submit prior art, and rewarding them with fee reimbursement if successful,” and “Permitting post-grant review of patents by the USPTO prior to litigation.”

- 43See, e.g., Steve Seidenberg, Novel Ideas: PTO proposes a new suite of patent products to streamline applications, InsideCounsel (Jan. 2007); D.C. Toedt, “Reengineering the Patent Examination Process: Two Suggestions,” 81 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 462 (1999): (suggesting the creation of a convertible “low end” patent (CLEP) and conducing patent examinations as administrative trials); and Dave A. Wyatt, A Radical View On The Future Of Substantive Patent Examination, Henry Goh Intellectual Property Updates (Q1, 2006).

- 44Economists Michele Boldrin & David K. Levine suggest amending the patent law to reverse the burden of the proof on patent seekers by granting patents only to those capable of proving that

- • their invention has social value

• a patent is not likely to block even more valuable innovations

• the innovation would not be cost-effective absent a patent.

See Cory Doctorow, “Economists call for patent and copyright abolition,” Boing Boing (March 11, 2009); see also Boldrin & Levine’s Against Intellectual Monopoly (2008).

- • their invention has social value

- 45See, e.g., RIAA Wants $1.5 Million Per CD Copied, Slashdot (Jan. 30, 2008); Ford Slaps Brand Enthusiasts, Returns Love With Legal Punch, AdRants (Jan. 14, 2008) (Ford Motor Company claims that they hold the rights to any image of a Ford vehicle, even if it’s a picture you took of your own car); Jacqueline L. Salmon, NFL Pulls Plug On Big-Screen Church Parties For Super Bowl, Washington Post (Feb. 1, 2008) (NFL prohibits churches from having Super Bowl gatherings on TV sets or screens larger than 55 inches); Internet pirates could be banned from web, Telegraph (Feb. 12, 2008) (British proposal to punish individuals who illegally download music by banning them from the Internet); John Tehranian, Infringement Nation: Copyright Reform and the Law/Norm Gap, Utah L. Rev. (forthcoming; SSRN); Cory Doctorow, Infringement Nation: we are all mega-crooks, Boing Boing (Nov. 17, 2007); Court Says You Can Copyright A Cease-And-Desist Letter, Techdirt (Jan. 25, 2008); Kinsella, Battling the Copyright Monster, Mises Blog (June 19, 2006); idem, Copyright Kills Amazing Music Project, Mises Blog (Jan. 2, 2008); idem, “Fair Use” and Copyright, Mises Blog (Aug. 17, 2007); idem, Copyrights and Dancing, Mises Blog (Feb. 20, 2007); idem, The “tolerated use” of copyrighted works, Mises Blog (Oct. 27, 2006); idem, Copyright and Birthday Cakes, Mises Blog (June 16, 2005); idem, Heroic Google Fighting Copyright Morass, Mises Blog (June 2, 2005); idem, Copyright Gone Mad, Mises Blog (Apr. 14, 2005); idem, Copyright and Freedom of Speech, Mises Blog (Nov. 8, 2004). See also Joost Smiers & Marieke van Schijndel, Imagine a World Without Copyright, International Herald Tribune (Sat. Oct. 8, 2005); Jessica Litman, Revising Copyright Law for the Information Age, 75 Oreg. L. Rev. 19 (1996); Kinsella, Copyrights in Fashion Designs?, Mises Blog (Sep. 27, 2006); Kinsella, Britain’s Copyright Laws, Based on a 300-Year-Old Statute, Desperately Need Reshaping for the Digital Age, Mises Blog (Nov. 2, 2006). For a humorous parody of copyright abuses by the RIAA, see CD Liner Notes of the Distant Present, Something Awful (Jan. 3, 2008).

- 46See, e.g., Lou Carlozo, Teen’s charity name draws the McIre of McDonald’s, Wallet Pop (Jan. 17, 2010) (McDonadl’s claims Lauren McClusky’s use of “McFest” for the name of a series of charity concerts she puts on infringes its “McFamily” brand); Chip Wood, A Bully-Boy Beer Brewer, Straight Talk (Oct. 16, 2007); 9th Circuit Appeals Court Says Its Ok To Criticize Trademarks After All, Against Monopoly (Sept. 26, 2007); Kinsella, Trademarks and Free Speech, Mises Blog (Aug. 8, 2007); idem, Beemer must be next… (BMW, Trademarks, and the letter “M”), Mises Blog (Mar. 20, 2007); idem, Hypocritical Apple (Trademark), Mises Blog (Jan. 11, 2007); ECJ: “Parmesian” Infringes PDO for “Parmigiano Reggiano,”I/P Updates (Feb. 27, 2008); Mike Masnick, Engadget Mobile Threatened For Using T-Mobile’s Trademarked Magenta, Techdirt (Mar. 31, 2008).

- 47See Kinsella, Improving Copyright Law: Baby Steps, Mises Blog (Feb. 24, 2005); Timothy Lee, Orphan Works Legislation Would Be A Small But Important Step Toward Copyright Reform, Techdirt (Apr. 29, 2008).

- 48See Kinsella, “Copyright Is Very Sticky!“ Mises Blog (Jan. 14, 2009).

- 49See Kinsella, World’s Fair Use Day, Mises Blog (Jan. 6, 2010); idem, “Fair Use” and Copyright; idem, The “Tolerated Use” of Copyrighted Works; idem, Copyright and Birthday Cakes; idem, Heroic Google Fighting Copyright Morass.

- 50An example of an egregious award resulting from the current statutory damages scheme was the recent $220k verdict against Jammie Thomas for sharing 24 songs. The jury awarded $9,250 in statutory damages per song for 24 songs; it could have been up to $150,000 per song, or $3.6M. See Eric Bangeman, RIAA Trial Verdict Is In: Jury Finds Thomas Liable for Infringement, ars technica (Oct. 04, 2007).

Archived comments here, here, here, here, and reproduced below.

Comments (154)

*****

{ 252 comments }

January 29, 2010 at 4:03 am

January 29, 2010 at 4:03 am-

Okay, so I can print 1 trillion U.S. dollars copies since they are not scarce because two people can have copies at the same time.

Yes…but you can’t print a trillion ounce-of-gold copies – which is precisely why gold is a better money than fiat paper!

January 29, 2010 at 5:15 pm

January 29, 2010 at 5:15 pm-

And do you think it is somehow wrong for a property owner to gain benefit from his property over and over again by keep renting it?

How is that any different than gaining the same benefit once by selling it? You’re confused.

January 29, 2010 at 5:21 pm

January 29, 2010 at 5:21 pm-

You can get linux for free but you want Windows

Most people get Windows for free, and pay for Linux…but who in their right mind would want Windows?

January 29, 2010 at 6:43 pm

January 29, 2010 at 6:43 pm-

IP doesn’t create a positive obligation on other people; it just puts limits on what they can do with their property, like other property rights do.

But other property rights don’t — see Stephan’s post a little above yours!

January 29, 2010 at 7:52 pm

January 29, 2010 at 7:52 pm-

Peter Surda-

your whole premises rest on an arbitrary definition of “homesteading”. Just like many other IP proponents, you draw an arbitrary line on the causality scale. Maybe it would help if you tried to explain where exactly you draw the line, then you’d realise it’s arbitrary.

Not at all. The first Harry Potter novel is a creation. All duplications, authorized or unauthorized, depend on the first one. Yes, there is causality, but it is relatively easy to identify.

This is just a first step in the argument. In the second one, you need to establish how far the homesteading reaches and what takes priority if there is a conflict. That is the whole point of my objection. Causality does not answer that.

Self-ownership has its own set of proofs in natural rights. One inhabits one’s body first so they own their body and their labor, etc. Otherwise there is some kind of state of slavery – either another person (including parents) or the state would “own” the person so this is rejected. From there you simply branch out to homesteading.

It does not answer whether children’s ownership of themselves or parent’s ownership of themselves takes precedence (logically, the parent’s should, because it is predates the child).

No, rejected by self-ownership. One inhabits one’s body first, even in the womb. Then there are the slavery arguments. Some concessions are made to parents making decisions, etc. but these end on emancipation, adulthood, etc. Plus there are exceptions like fraud, abuse, neglect, other tortious and criminal conduct, etc.

It does not answer whether only “good” influences should be considered, there is no reason why Soviet Union should not co-own Atlas Shrugged. Besides, back to my original objection, there is no way to distinguish between immaterial goods and externalities. But according to theory, you can own the former but not the latter.

The Soviet Union’s claim would be rejected by both self-ownership (otherwise it’s slavery) and homesteading.

Your externality arguments are somewhat nebulous. I adressed the examples you gave. IP owners decide how they are going to profit by weighing what externalities they can forsee. But this isn’t too different from the process with physical goods and there isn’t too much controversy over that.

What is “proper party”? That’s just another arbitrary assumption. Governments also claim that some transactions are invalid without them being involved, but that does not make it true.

In a transaction there is a consensual buyer and a consensual seller. If someone is unilaterally taking property it isn’t a market transaction. And there is no legitimate price signaling occurring.

Exclusion in material goods is not “enforced”, it “is”. It is the natural feature of those things. It exists regardless of laws or people.

Not exactly with land. Physical exclusion in real estate is only truly present when we are talking about very small pieces of land when the owner is present. Plus land ownership and homesteading has to be widely recognized and acknowledged so a market in the asset can occur, if not by the state then by some other body or association.

It is.

Not any more than buying land is. Others are free to homestead or buy land to compete. No one is forcing any exchanges, like what occurs in the “duplication is equivalent to creation” IP model.

This is only valid from your point of view. From my point of view, it’s the opposite: competitors homestead new grounds, and a monopoly prevents them from using it. From my perspective, those new grounds are externalities of the original.

Not just from my view. Doing away with IP creates a public, collectivist claim on individual labor and creates mispricing like socialism does.

Exactly! IP owner, just like anyone else causing externalities, should consider the effects before making his move, instead of complaining how little he gained by using an infeasible business model.

Just because you want to unilaterally take something without paying for it doesn’t make sale of that something “infeasible”.

There are already property rights in the physical, those are sufficient to address the most common and harmful effects of undesired activities.

Right, there are currently IP rights that take care of externalities there as well. If you can argue from the status quo, so may I. Homesteading vests equivalent rights, status quo here I come.

This is merely another stage of the problem (i.e. you are trying to cure the symptom rather than the cause). The illicit photographer trespassed on physical property. When a woman with a miniskirt goes to a street, she needs to make herself informed about the rules regarding photographing that the street owner does (some might permit photos, some might not). There is no need for IP from this perspective.

Not at all, the camera placer might have been an invited guest. I was just illustrating how people are already aware of most of the externalities. People know they have less control over their image when they appear in public as opposed to when they are in their dwelling, etc.

But what does this mean? I fail to see how this can mean owning anything apart from that which is in one’s own head. The line where you draw the distinction between immaterial goods and externalities is arbitrary. That’s what you need to recognise. IP is the claim of ownership of other people’s minds. It does not bother you here, but it bothers you with children and Ayn Rand. You need to explain this dichotomy.