In the 22 years I’ve been writing seriously, I’ve never registered a copyright with the US Copyright Office. In the beginning, I thought it was wonderful that once I wrote something, it was protected. Somewhere in that first year of writing, though, I learned that I didn’t stand much of a chance in winning a copyright case in court without registering a copyright with the US Copyright Office.

In my first year of serious writing, I made what averaged out to a couple hundred dollars a month writing independent (i.e., creator owned) comic books, short stories, and the occasional article. The $20 fee to register copyright for each substantial work — when I was producing, in some months, close to a dozen substantial works — was more than I could afford. So I took my chances and never registered a copyright.

I never really thought about it until a friend asked me how I’d view a world without copyright as a writer. My first thought was a knee-jerk reaction: “That would be terrible — we need copyright protection!” But when I thought about how I’ve never had to enforce a copyright in all my years writing, I came to this conclusion: copyright really benefits those who use it to coerce writers, artists, musicians, consumers, and others.

In the News

In much the same way that if somebody tells me to look for purple things throughout my day I will notice purple more than usual, I started noticing articles about copyright abuse: musicians producing original work being accused of stealing sounds; writers receiving cease and desist letters for writing parodies; independent filmmakers willing to offer what they were doing for free via bit torrents seeing their means of distribution shut down because some people used the same services to share movies. Just a few weeks ago, my wife loaded a video on YouTube that was flagged because she used a Creative Commons Haydn piano sonata. And just yesterday, I came home and read this on BoingBoing.net.

Add to that how it seems a handful of years can’t pass by when one doesn’t read about Disney — a company that largely exists from creating derivative works — claiming others are creating derivative works of their derivative works. If it weren’t so stifling, it would almost be humorous.

Fortunately, innovation often outpaces coercion, and there are now other ways for musicians and filmmakers to get their work out there. But at the time of Napster and the beginning of bit torrents, there were people offering their art and having their means of distribution shut down by corporations, organizations, and the government — all in the name of copyright protection.

The Writer’s Turn

Just as musicians and filmmakers have had to deal with the suppression of their rights to create and distribute their work by non-traditional means in recent years, writers are now getting their turn. Books weren’t the easiest thing to copy in the past; it was easier to just buy or borrow a book than to copy War and Peace one page at a time on a Xerox machine. Because of this (and many other reasons), publishing has always been a slow industry with gatekeepers deciding who got in…and who stayed out.

With the rise of e-books, novels are now like albums — something that can be copied, shared, and read on computers, tablets, and smart phones. Even with early demand, publishers were slow to catch on. At a 2009 South by Southwest panel called “New Think for Old Publishers,” publishers walked away looking like a lonely middle aged guy desperately trying to convince a bunch of 20-year-olds that he’s still hip. It wasn’t until Amazon pushed for e-books that people really paid attention.

The Big River (Apparently Full of Piranha)

Amazon quickly made the e-book a viable thing through the innovation of the Kindle and the means by which they were able to distribute e-books. While other e-readers existed, it’s safe to say it took Amazon to make the e-book an everyday thing. And with that quick success (Amazon making the market and then claiming 90%), came the cries that Amazon wasn’t playing fair. They were a monopoly with aggressive tactics — that was the claim by some companies angry that they didn’t think of it all first!

It’s hard to feel bad for Barnes and Noble — a company that aggressively targeted small booksellers in an effort to drive them out of business — crying foul when they are on the receiving end of similar tactics they once used. It’s kind of like seeing a playground bully bested in battle by a crafty, tough nerd.

I’ve heard people say “Amazon is a monopoly! They own the market share of e-books!” Why shouldn’t Amazon have the biggest share when they were the ones who thought, “Let’s make publishing easy and give indie publishers a 35% royalty on anything between $.99 – $1.99, and a 70% royalty on anything more than $1.99.”?

A seventy percent royalty is unheard of! Why wouldn’t writers consider self-publishing e-books when traditional royalties on hardbacks are considerably less than Amazon’s low end of 35%. When I self published comic books back in the 90s and got 40% for each book sold through the direct market, I thought it was the greatest deal in the world! And now I can do that with novels that cost next to nothing to produce.

The “Evils” of Amazon’s “Monopoly”

Amazon no longer has a 90% share of the e-book market; in large part because their aggressive tactics and “stranglehold” on the industry opened the door for other booksellers, publishers, and e-reader/tablet manufacturers. The Nook, in part, owes its life to the Kindle — and Barnes and Noble followed Amazon’s lead with an online store and e-book sales. Barnes and Noble and other companies are all benefiting from Amazon’s innovation.

But there are still those who think otherwise. My favorite Internet battle in recent weeks has been J.A. Konrath and Barry Eisler’s challenge to Author’s Guild president, Scott Turow. (More about that here and here.) The quick version: Scott Turow came out in support of the agency pricing model in publishing, and in the process, attacked the way Amazon does business. Instead of siding with the interests of the writers he’s supposed to support, he sided with the pricing model used by major publishers that puts a smaller percent of royalties in writers’ pockets.

If you’re not familiar with Konrath and Eisler, they are midlist writers who broke away from traditional publishing and did it on their own, using e-books as their main product. Konrath was unsuccessful at convincing his then publisher to re-release his out-of-print books. He was told it wasn’t worth it. He fought for the rights, released them as e-books, and they’ve pulled in decent 6-figure totals. Eisler, seeing Konrath’s success, walked away from a 2-book, $500,000 publishing deal to do it himself. (He says it was more than worth it.)

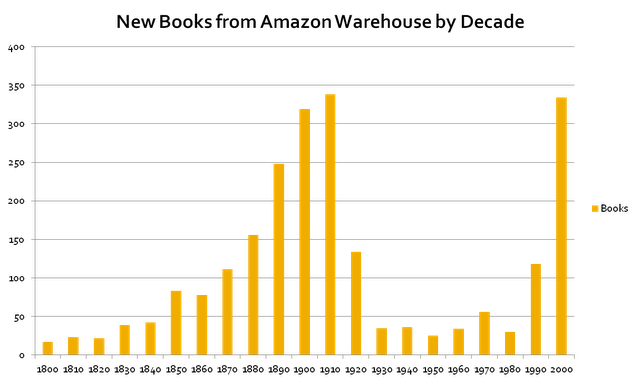

When the same friend who challenged me to imagine a world without copyright sent me the graph featured by Stephan here last Saturday, I was not at all surprised to see Amazon moving more books in the public domain — and then since the rise of print-on-demand technology and e-books. The dip in the numbers of books released during times of industry coercion through copyright claims says it all.

The Traditional Way

I’m lucky enough to be friends with a handful of writers much more successful than me. A few of those writers — and a couple writers I follow online — have made no secret that they would love to see fewer writers being published. Fewer writers being published means more for them. In some ways, I find it hard to totally fault them; they are writers who came up in a time of gatekeepers. Once invited to that side of the wall, they want to cling to what they have — even if they are the same writers who once complained about gatekeepers holding them back.

Should one believe I’m bitter because I’m not on that side of the wall, I am not opposed to going the traditional publishing route. While genre fiction has seen e-book successes like Amanda Hocking and John Locke, upmarket and literary fiction doesn’t have a similar kind of e-book success story. Despite getting rejections letters that amount to, “Loved this–you’re a talented writer, but…it’s too quirky and I don’t know how I’d market this,” I still try to find success the traditional way with some stories. But I’m also a fan of e-books. I’m an even bigger fan of having so many options!

Where I Stand

I offer some of my writing for free, and some for $.99 – $2.99 in the hope that people will buy it instead of copying and distributing it themselves. But if people want to copy and share my writing (everything I offer is DRM-free), I’m fine with that. While I want nothing more than to write full time, I am not owed a career as a writer.

There seems to be a belief that if one works hard at a creative pursuit that it’s somehow more noble than the person making a widget or other product. (And having to fight patent law like some writers fight copyright law.) I love what I do, but it’s no more special or requiring extra protection than a guy who loves making bars of soap.

To those who say we need at least some kind of IP law to protect me, since the night a friend challenged me to imagine a world without copyright, I’ve realized that if I’m doing my job right, you know who I am. If you don’t know who I am (and most people don’t), I need to work harder to generate excitement about what I do so people come to me for my writing — not go to others. But even if others released my writing, I find it hard to lay claim to your interpretation of the stories I write as you see them in your heads.

In addition to being paid to write, I’ve been paid for photographs accompanying travel articles I’ve written. I have a hard time believing that I should be extended copyright for those photos, when all I’ve done is capture what’s already there. If I do my job as a writer — like a photograph — I’m simply capturing what’s already there around me. And I find it quite arrogant — even bordering on hostile — to lay claim to my surroundings.

* * *

About Christopher Gronlund

Christopher Gronlund is a writer living in Texas. His first novel, Hell Comes with Wood Paneled Doors, can easily be seen as a derivative of National Lampoon’s Vacation, Stephen King’s Christine, and TV’s Wonder Years. He blogs at thejugglingwriter.com.

Christina Mulligan, Visiting Fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School, discusses Her new paper, co-authored with Tim Lee, entitled, Scaling the Patent System. Mulligan begins by describing the policy behind patents: to give temporary exclusive rights to inventors so they can benefit monetarily for their inventions. She then explains the thesis of the paper, which argues that the patent system is failing because it is too large to scale. Mulligan claims that some industries are ignoring patents when they develop new products because it is nearly impossible to discover whether a new product will infringe on an existing patent. She then highlights industries where patents are effective, like the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. According to Mulligan, these industries rarely infringe on patents because existing patents are “indexable,” meaning they are easy to look up. The discussion concludes with Mulligan offering solutions for the current problem, which includes restricting the subject matter of patents to indexable matters.

For the sake of the simplicity of this blog post, I am going to assume all of my readers have at least a basic familiarity with both the ideas of free software advocates like Richard Stallman and Eben Moglen (though I try to link extensively to references within the post). For most of my libertarian readers, understanding the free software movement is very likely going to require a bit of reading unless you are a GNU/Linux geek. The

For the sake of the simplicity of this blog post, I am going to assume all of my readers have at least a basic familiarity with both the ideas of free software advocates like Richard Stallman and Eben Moglen (though I try to link extensively to references within the post). For most of my libertarian readers, understanding the free software movement is very likely going to require a bit of reading unless you are a GNU/Linux geek. The