Update: see

- Dean Baker: Patents Cost Almost $1 Trillion A Year (July 12, 2022)

- Patent Trolls Cost The Economy Half A Trillion Dollars since 1990

- Cost to Google to Pre-Screen YouTube Videos to Prevent Copyright: $37 Billion Per Year

- Software Industry Needs 6 Million Patent Attorneys and $2.7 trillion per year to avoid infringing software patents

From Mises Blog (Archived Comments below) 09/29/2010

Costs of the Patent System Revisited September 29, 2010 by Stephan Kinsella

In my 2007 post What Are the Costs of the Patent System? (discussed in “Reducing the Cost of IP Law“) I tried to estimate the cost of the patent system (see also my reply to David Friedman in the thread to “Volokh’s David Post: The High Cost of Copyright”; Yet Another Study Finds Patents Do Not Encourage Innovation; and There’s No Such Thing as a Free Patent).

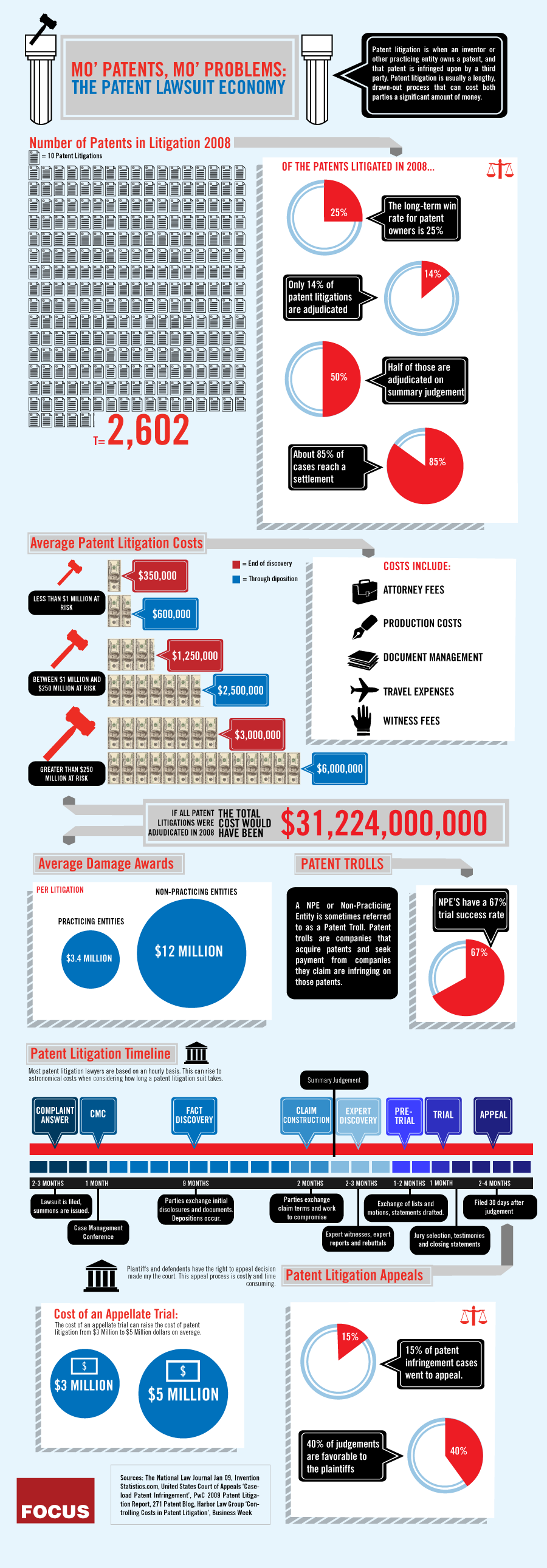

I concluded there is at least a $31 billion a year net loss to the US economy from the patent system. Take a look a this fascinating graphic from Anatomy of a Patent Litigation. It estimates about $31 billion a year as the cost of patent litigation in the US. These cost estimates are not astounding. What is astounding is that anyone thinks this mercantilist statist monstrosity is libertarian or free market.

Update: Note, my previous estimate was based on a conservative assumption that patent litigation costs $20B a year. The more recent statistics as indicated in the chart is $11B higher. That means my original estimate of $31B net loss should be more in the $42B net loss per year range.

Update: From a conversation with Grok (March 5, 2025):

Note that Grok told me “Litigation costs—$3.3 billion annually in the U.S. by some estimates (RPX Corp, 2020)” (apparently referring to patent litigation costs from litigation by non-practicing entities, or NPEs, i.e. patent trolls, which is only a subset of all patent litigation costs, which is itself only a subset of all costs of the patent system). However, when asked, it could not pinpoint it exactly and I have not found the reference yet. I did find: 2015 Report: NPE Litigation, Patent Marketplace, and NPE Cost. From p. 3 (see also pp. 5 & 72):

While our 2015 reporting indicates some evolution in the patent landscape itself (though somewhat limited to the lower end of the market and to certain sectors), our data also reflect significant progress in RPX’s pursuit of transparency in this chronically opaque marketplace. This year’s cost estimates are our most precise yet—the result of an expanded data set and increasingly sophisticated analysis. As always, we have revised historical estimates based on these gains. In the case of overall cost to industry, this revision has resulted in a downward adjustment to industry cost estimates that we have published in the past. Where we had estimated that NPE litigation costs industry in the range of $10 billion or more in direct expenses annually, we now estimate that number to be $7 – 9 billion.

***

-

Critical Voices: A small subset of legal scholars and practitioners has historically questioned the patent system’s efficacy. For example, some economists and libertarian-leaning thinkers (not necessarily patent attorneys) argue that patents stifle innovation by creating monopolies, a view occasionally echoed in legal blogs like Patently-O. Yet, these critiques rarely come from practicing patent attorneys, who are more likely to push for reform than abolition.

-

Industry Trends: The rise of “patent trolls” and high-profile cases (e.g., Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank, 2014) have frustrated some practitioners, particularly in tech, where patents can be invalidated easily. A 2021 Legal Examiner article noted a decline in patent lawyers relative to demand, hinting at dissatisfaction with aspects like software patent instability, but not systemic rejection.

-

Numbers Estimate: If we assume 45,000 patent practitioners in 2023, even a generous estimate of outspoken critics might place opposition at 1-5% (450–2,250 individuals). Of these, those advocating outright abolition—rather than reform—would be a smaller fraction, perhaps 0.5–1% (225–450 individuals). This is speculative, as no survey confirms it, but it aligns with the profession’s incentives.

-

In Favor: Likely 80–95% (36,000–42,750) of U.S. patent attorneys support the patent system’s existence, though many may seek tweaks.

-

Opposed: Perhaps 1–5% (450–2,250) express significant opposition, with a subset—0.5–1% (225–450)—potentially favoring abolition.

-

That inventors need monopoly profits to justify the risk and cost of innovation.

-

That without patents, inventions would remain secret or underutilized, slowing progress.

-

That the system’s costs (e.g., litigation, monopolistic pricing) don’t outweigh its benefits.

-

Historical Correlation: The U.S. patent system’s growth (from 36 patents in 1790 to over 300,000 annually by the 21st century) coincides with industrial and technological booms. Scholars like B. Zorina Khan (The Democratization of Invention, 2005) argue that patents democratized innovation by protecting individual inventors, not just corporations, spurring 19th-century advances.

-

Pharmaceuticals: Studies like one from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER, 2004) suggest patents significantly boost R&D in drug development, where high upfront costs (often $1 billion+ per drug) and long timelines need protection to ensure returns. Without patents, generic copying could collapse investment.

-

Patent Counts as Metrics: Firms with more patents often lead innovation sectors (e.g., tech giants like IBM or Qualcomm). A 2016 USPTO report tied patent-intensive industries to 38.2% of U.S. GDP, implying a link to economic activity, if not direct causation.

-

Cross-Country Comparisons: Nations with stronger patent systems (e.g., U.S., Japan) tend to have higher innovation rates (per OECD data) than those without, though correlation isn’t causation.

-

Machlup’s Legacy: Post-1958 studies haven’t fully resolved his doubts. A 2004 paper by Boldrin and Levine (The Case Against Patents) argues that patents often hinder innovation by creating monopolies that block follow-on inventions. They cite historical examples like steam engines, where patent disputes delayed improvements.

-

Software and Tech: The Alice decision (2014) and subsequent patent invalidations suggest many software patents were vague or redundant, clogging courts rather than spurring breakthroughs. Critics like the Electronic Frontier Foundation argue that open-source models (e.g., Linux) innovate faster without patents.

-

Economic Costs: Litigation costs—$3.3 billion annually in the U.S. by some estimates (RPX Corp, 2020)—and “patent trolling” (non-practicing entities extorting fees) drain resources. A 2011 study by Bessen and Meurer (Patent Failure) estimated that outside pharmaceuticals, patent costs exceed benefits for firms.

-

Historical Alternatives: Pre-patent societies (e.g., Renaissance Italy) or patent-free periods (e.g., Switzerland until 1888) still saw innovation via trade secrets or first-mover advantages, per Petra Moser’s research (AER, 2005). This suggests patents aren’t the only driver.

-

Pro-Patent: In specific fields (e.g., pharma, biotech), patents likely stimulate innovation by securing investment. Aggregate data (GDP, patent counts) suggests a positive role, and patent attorneys I referenced earlier “tend to align” with this view because their clients—innovators—rely on it.

-

Anti-Patent: In other domains (e.g., software), patents may stifle incremental progress, and their absence doesn’t halt innovation entirely. Machlup’s call for humility persists—no one can prove the system’s net benefit across all sectors.

-

Focus: The $3.3 billion likely covers direct costs (legal fees, settlements, judgments) tied to NPE litigation in the U.S. for 2020. RPX distinguishes NPE costs from operating company disputes, as NPEs drive disproportionate expense due to their assertion-heavy strategies.

-

Data Sources: RPX collects data from court filings, client inputs, and proprietary tracking of over 55,000 companies sued since 2010 (per their site). For 2020, this might include fallout from TC Heartland (2017) venue shifts or Alice (2014) eligibility rulings, which reshaped litigation patterns.

-

Context: Their 2018 Litigation Report noted 3,106 defendants added to patent suits, with NPEs and operating companies splitting roughly half each. By 2020, NPE activity had dipped then rebounded (per 2024 RPX blogs), suggesting $3.3 billion reflects a stabilized but still hefty cost amid evolving case law.

-

RPX Website: Check rpxcorp.com/insights or their blog archives for 2020 posts. Search “NPE Cost Report 2020” or “litigation costs 2020” on their site.

-

Contact RPX: Their 2017 post lists reports@rpxcorp.com for inquiries about cost studies—emailing might yield the 2020 report or confirmation.

-

Third-Party Sources: Look for 2020 articles from Law.com, Reuters, or IP blogs (e.g., Patently-O) citing RPX’s $3.3 billion figure, as they often relay such stats.

-

2015 Report: NPE Litigation, Patent Marketplace, and NPE Cost

Released May 15, 2016, this report (available via RPX’s blog archives) provides a broad overview of NPE litigation costs based on their annual cost study. It doesn’t give a single headline figure like $3.3 billion but offers insights into cost trends. For instance, it notes that “cost of NPE litigation in 2015 dipped from 2014—especially for certain types of cases,” and cites settlement data showing pre-AIA (America Invents Act) settlements averaged $2.1 million per case, dropping to $1.5 million post-Alice (2014). While not an aggregate annual estimate, it suggests a framework where RPX tracks millions-to-billions in total costs across thousands of cases. The full report, with specific dollar amounts, was exclusive to participants, but this public summary confirms their methodology. -

2017 Blog Post: Patent Litigation Cost Analytics

On June 14, 2017, RPX posted “Patent Litigation Cost: Is the Market Adjusting?” This discusses their ongoing NPE Cost Study, stating they’ve “studied the billions of dollars companies collectively spend every year on NPE litigation.” No exact 2017 figure is public here, but it reinforces that RPX’s estimates routinely hit billions annually. The post highlights interactive cost analytics on RPX Insight, suggesting a 2020 update could’ve produced the $3.3 billion figure I mentioned, likely derived from similar litigation and settlement data. -

Later Trends (e.g., 2023/2024 Posts)

RPX’s Q1 2023 review (April 10, 2023) and Q3 2024 review (October 07, 2024) focus on litigation volume (e.g., 333 NPE defendants in Q1 2023) rather than costs, but they imply continuity with prior cost studies. The lack of a 2020-specific public blog post suggests the $3.3 billion might’ve been a subscriber-only stat or cited indirectly elsewhere.

-

A 2013 RPX post (“Large-scale NPE Economics,” July 17, 2013) doesn’t give a total but models a $200 million license as equivalent to resolving 370 median litigations at $600,000 each—implying a potential $222 million cost for just one portfolio. Scaling this to thousands of NPE cases annually supports a billion-dollar range.

-

Third-party sources, like a 2016 Forbes article citing RPX, note their tracking of litigation costs, but no 2020-specific public RPX blog I can access today nails down $3.3 billion exactly.

***

September 29, 2010 at 5:25 pm

September 29, 2010 at 5:25 pm-

Bahahahaha! I just finished reading the comments on the other post. Too funny

“What is astounding is that anyone thinks this mercantilist statist monstrosity is libertarian or free market.”

Is that the reason for the flood of comments when IP is the issue? It seems obvious that the invisible realm where ideas come from cannot be designated as exclusive which means that ideas are destined to be put into the service of humankind in the quickest way possible.

Well, I guess you’ve basically conceded the utilitarian side. If the cost of the patent system is only $31 billion, that’s probably a lot less than the total consumer surplus resulting from goods that were created specifically to patent and put into use. Or is there a line in your calculation where you netted this out?

Thanks for the evidence.

September 29, 2010 at 5:10 pm

September 29, 2010 at 5:10 pm-

Re: Silas Barta,

Well, I guess you’ve basically conceded the utilitarian side. If the cost of the patent system is only $31 billion, that’s probably a lot less than the total consumer surplus resulting from goods that were created specifically to patent and put into use.

More likely the total amount consumers have to spend MORE (instead of less) to obtain those very products.

September 29, 2010 at 6:00 pm

September 29, 2010 at 6:00 pm-

Consumer surplus is the benefit to the consumer *net* of having to pay those costs.

September 30, 2010 at 10:29 am

September 30, 2010 at 10:29 am-

Re: Silas Barta,

Consumer surplus is the benefit to the consumer *net* of having to pay those costs.

That makes no sense. What’s “consumer surplus”?

September 30, 2010 at 12:11 pm

September 30, 2010 at 12:11 pm-

Would you like an Econ 101 textbook reference, or …?

September 30, 2010 at 4:14 pm

September 30, 2010 at 4:14 pm-

Re: Silas Barta,

Would you like an Econ 101 textbook reference, or …?

YOUR definition of “Consumer Surplus” will suffice.

October 1, 2010 at 3:35 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:35 pm-

Okay. The one in the Econ 101 textbook.

September 29, 2010 at 5:37 pm

September 29, 2010 at 5:37 pm-

It’s like you only read this post and didn’t partake in a debate on the last post. Intriguing.

I’m not hoping to get into a utilitarian debate here but “costs” are subjective, Silas. The post above highlighted the objective dollar cost of litigation. It’s a blog entry and I didn’t see any attempt to quantify subjective opportunity costs or other associated costs of IP. You’ve countered an argument that was not even made by assuming away subjective costs. Like I said, not wanting to get into a utilitarian debate here, but dude “those in glass houses…”

The links appear well chosen and are likely to prove useful for anyone wanting to understand the itopic in greater detail. Care to join a few of us in that camp?

September 29, 2010 at 6:04 pm

September 29, 2010 at 6:04 pm-

North, I don’t see how you find my comment irrelevant or unhelpful. An IP opponent is going to have to show costs of the patent system as being MUCH higher than $31 billion to have a shot at showing it’s a net loss. (And not that IP proponents defend the specific, inefficient system that exists, which would be like expecting property proponents to defend a despotic regime that claims to enforce “property rights”.)

You see, it’s not enough to have citations. They have to be *relevant* citations, and you need to know *why* they’re being cited. If it turns out that they’re irrelevant to the issue at hand, then it doesn’t help you much to follow them, now, does it?

(And incidentally, I already did a comparison of the costs of the patent system to the costs of the property system to show the fruitlessness of the whole exercise. See my comment from the previous discussion.)

September 29, 2010 at 7:21 pm

September 29, 2010 at 7:21 pm-

Come on Silas, you honestly are going to claim a cost of patents being $31 billion a year is proof of a net benefit? If it is so obvious that $31 billion proves a benefit then it should be easy for you to show a study or produce one that proves the utilitarian case. Yet, no study can be found that supports that claim and in fact most say the exact opposite. So if you are going to make a utilitarian argument then the burden of proof is on you. If you can’t prove your case then you shouldn’t support the position.

September 30, 2010 at 12:26 am

September 30, 2010 at 12:26 am-

If govt regulations doubled the price of my food, sure I’d be willing to pay twice the cost to eat, and sure somebody would be making a lot of money from it, but only an idiot would say that “conceded the utilitarian” benefit of those regulations. Yet somehow a govt micro-regulation that controls how people use inventions, called patent, elicits that exact response.

September 30, 2010 at 9:20 am

September 30, 2010 at 9:20 am-

@David_C:

Higher food prices would mean lower consumer surplus. I am not relying solely on the fact that people pay more to buy things that are patented; the relevant comparison is to how much they *would* pay, minus what they have to pay.

Given a patent-dependent invention, the consumer surplus is higher, even with the “patent premium”, because without it being patented, you wouldn’t be able to buy it at any price — not much consumer surplus there.

So these aren’t the same cases at all, and you are being imprecise in equating them. Please treat this issue with more care.

September 30, 2010 at 9:24 am

September 30, 2010 at 9:24 am-

I guess every invention before the advent of the patent system in the 18th century would never have existed then.

Oh, wait…

September 30, 2010 at 10:12 am

September 30, 2010 at 10:12 am-

So, J._Murray, like every other IP opponent you can’t do any better than attack strawmen. Of *course* some inventions would exist whether or not there’s IP. No one disputes this. The fact that some inventions only exist because of IP does NOT imply that there have never been IP-independent inventions.

And look at that, you’ve forced me into a quadruple+ negative construction!

September 30, 2010 at 1:08 pm

September 30, 2010 at 1:08 pm-

Dear Mr. Barta,

(1) How many inventions have only been invented because of IP; (2) how can you be sure epistemologically; (3) is the amount more or less than the amount of inventions that have, because of IP, never been invented; and (4) assuming you believe the number of inventions that result solely from IP is creator than the number of inventions that were never invented because of IP, how can you be epistemologically sure that you have the proportions right?

Before answering, please see my thought experiment above regarding smell-o-vision televisions.

Best regards,

Alex Peak  September 30, 2010 at 2:29 pm

September 30, 2010 at 2:29 pm-

Dear Alexander_S._Peak,

(1) How many goods have only been produced because of physical property rights; (2) how can you be sure epistemologically; (3) is the amount more or less than the amount of goods that have, because of physical property, never been consumed; and (4) assuming you believe the number of goods that result solely from physical property is greater than the number of goods that were never produced/consumed because of physical property rights, how can you be epistemologically sure that you have the proportions right?

Before posting, make sure your arguments don’t work equally well against your own position.

Best regards,

Silas_Barta  September 30, 2010 at 2:57 pm

September 30, 2010 at 2:57 pm-

Typical Silas. First you justify IP on utilitarian grounds. Then when an argument comes along showing some of the costs, you declare that the benefits are much higher and obviously outweigh those costs. When someone asks you to justify your statement, you use your tiresome trick of avoiding the argument by changing trying to show that it does not hold for “physical property rights”.

One teensy problem there, Silas. Alexander never made the argument for property on utilitarian grounds. YOU did. Therefore the burden of proof is on YOU. If you can’t show that the benefits accrued outweigh the costs, then your utilitarian argument is based on faith, not logic. Maybe it is becoming clear to you why the utilitarian angle is a dead end?

October 1, 2010 at 5:53 pm

October 1, 2010 at 5:53 pm-

Dear Mr. Barta,

In response to my asking how many inventions have only been invented because of IP, you respond by asking, “How many goods have only been produced because of physical property rights[?]”

In answer to your question, I would say that virtually all goods that are produced have been produced because of rights to naturally-scarce physical property, and I would say that this is reasonable to believe because human survival requires that humans consume, and human consumption is exclusive. You and I cannot eat the same apple, so we must decide either (1) to let me eat all of it, (2) to let you eat all of it, or (3) to split it. Even when we split it, however, we have to decide who gets what half; it’s impossible for us to both consume the same exact atoms (unless we do some disgusting stuff not worth going into here). Since human survival depends upon exclusive control to justly-acquired alienable goods, it stands to reason that humans would see little reason to produce were it not for the very property rights that allow them to use their produce in order to sustain life. This isn’t to say that no production ever occurs for charitable reasons; undoubtedly, some percentage of goods have been produced beyond the amount produced solely because of physical property rights, although I suspect that a far larger proportion of goods that have been produced or human consumption have been produced because of physical property rights.

It seems the exact opposite is the case with regards to intellectual “property.” I’d suspect that only a tiny percentage of the inventions ever invented were invented because of patents. Thus, I don’t see how my arguments work equally well against my own position. While physical property rights are naturally necessary for human survival, intellectual “property” is not.

My point in previously asking my four-part question is that, even if you’re correct that many good inventions are only invented because of IP, you have no way of being sure that, from a utilitarian stance, whether IP is a bigger asset or a bigger liability. Your counter-point is not very strong because it is far easier to imagine a world with no property rights than to imagine how a world would play out with physical property rights yet without intellectual “property rights.” Without any physical property rights, existence would be dog-eat-dog, or perhaps tribe-eat-tribe, and life would be poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Sincerely yours,

Alex Peak  October 2, 2010 at 5:38 am

October 2, 2010 at 5:38 am-

Dear Silas,

How many goods have only been produced because of physical property rights

I see your preconceived biases continue to plague you (alternatively, you could be just plainly dishonest, but I’ll give you the benefit of doubt). I thought you agreed that IP does not increase the scope or coverage of property rights, merely redistributes them? That would of course mean that the difference between a system of physical property rights and a system with a mix of physical property and IP is in the distribution, rather than in something “missing”. Well then, what is the system that represents the third one you are comparing to, the one without physical property rights? What rules are used for distributing the coverage? Or, let me guess: you “forgot” that there is nothing “missing”, and neglected to update your arguments based on that.

September 30, 2010 at 1:02 pm

September 30, 2010 at 1:02 pm-

Mr. Barta writes, “because without it being patented, you wouldn’t be able to buy it at any price.”

I reject this view, as I explain above. See above.

Sincerely yours,

Alex Peak September 30, 2010 at 1:08 pm

September 30, 2010 at 1:08 pm-

You reject it without reasoning, thinking that I don’t understand why the first mover has an inherent advantage. In reality, I understand that perfectly, and simply note that it’s far from sufficient to justify the investment in many good ideas, such as cancer cures and Viagra. But we’re just missing the “unseen” … right?

Use a different photo, please.

September 30, 2010 at 5:14 pm

September 30, 2010 at 5:14 pm-

How do you know it’s far from sufficient? How do you know that there aren’t other methods to reach the same objective that don’t rely on aggression?

Gee, if there were no real property rights there would be no real property rights disputes either.

September 29, 2010 at 8:26 pm

September 29, 2010 at 8:26 pm-

That’s the thing, there is nothing real about IP or patents. They aren’t fungible, the inventor’s utility isn’t being reduced. No one is stealing the product itself. No materials are being lost. The only “loss” is the assumption that all future individuals which wish to use the product *MUST* patron him or simply do without. They are unable to produce the product for themselves or purchase the product from some other provider.

Granting a patent or copyright to one individual violates the tangible property rights of everyone else who isn’t a patent holder by dictating what they can and can’t do with their own property. IP doesn’t protect property, it violates it.

September 30, 2010 at 9:23 am

September 30, 2010 at 9:23 am-

And broadcasting radio waves at a given frequency doesn’t stop you from broadcasting at that frequency either, so I guess there’s no loss there, too. Granding an EM spectrum right dictates what *I* can do with *my* transmitter on *my* property, and what EM waves going through *my* property I can desctructively interfere with.

What freaking socialism.

September 30, 2010 at 9:26 am

September 30, 2010 at 9:26 am-

I’ve never dealt with someone so dense that they’ve forgotten the concept of homesteading on four separate occasions. Further, the EM spectrum IS tangible ownership because it DOES fit the mold of property. Another individual attempting to use it DOES impede the ability of the original claimant to utilize the spectrum. Thus it is a violation of ownership. Inventions cannot be taken away because another individual producing the same product, either for self or sale, does NOT impede on the ability of the original inventor’s ability to make the same product. It only changes what the individual can trade for the invention. Property rights =/= profit rights. Profit rights do not exist.

Socialism is using government force to TAKE something from someone else to distribute it to others. Tell me how making something that someone else invented, of my own accord, with my own materials, without any force involved, is socialism. It fails since neither government nor force are involved. Thus, it is not socialism.

September 30, 2010 at 10:17 am

September 30, 2010 at 10:17 am-

@J._Murray:

First, drop the insults.

Another individual attempting to use it DOES impede the ability of the original claimant to utilize the spectrum.

That’s my very point! Everything depends on *which* use you consider relevant. Just as you can dismiss IP claims by saying, “hey, *you* can still use the idea”, I can likewise dismiss EM spectrum claims by saying, “hey, you can still make waves at that frequency” — it’s just as irrelevant.

Oh, what’s that? You say you *want* to be able to transmit *information* through the aether, and can’t do that when others are using “your” frequency? Well, what entitles you to the right to transmit information, which requires a claim on the tangible property of others?

Seriously, read my actual case before making these arguments. You can start here.

Property rights =/= profit rights. Profit rights do not exist.

Well then it’s a good thing that IP rights are not a right to profit, don’t you think?

September 30, 2010 at 4:25 pm

September 30, 2010 at 4:25 pm-

EM frequencies are a candidate for property rights because they are scarce and therefore use of them is physically exclusive. Ideas, once transmitted, may reside in scarce medium (RAM, disk, brain, etc) but themselves are not scarce; their use is not physically exclusive by definition. Granting property in ideas does not resolve a conflict over the use of an idea since an idea was not physically exclusive to begin with (such as an idea to use a computer to store ideas). Worse, it introduces a new conflict over the use of the scarce physical medium in which instances of that idea reside (RAM, disk, brain, etc).

September 30, 2010 at 1:35 pm

September 30, 2010 at 1:35 pm-

Silas, I refuted this argument like a year ago, several times actually, yet you repeat as a mantra. Your argument requires that the right to radio broadcasts is based on the pattern of the wave. But you can make the argument for rights to radio broadcasts without referring to pattern, for example through the right of not having your physical property (receiver) tempered with. Sure, it would probably result in a different distribution of ownership, but still would still cover the same scope. Therefore, you cannot make an argument that ownership of patterns is necessary in order to prevent people from broadcasting in a certain way.

September 30, 2010 at 2:26 pm

September 30, 2010 at 2:26 pm-

@Peter_Surda:

But you can make the argument for rights to radio broadcasts without referring to pattern, for example through the right of not having your physical property

Sure, and as *I’ve* said, if that’s your argument, then you must believe you have the right to deliberately impede EM waves passing over your land, and the right to stop light waves from bouncing off of e.g. billboards, trees, etc., and onto your property. Which is stupid.

If you don’t accept those arguments, then you can’t defend EM spectrum rights on the basis of “receive property rights”. Understand?

September 30, 2010 at 3:32 pm

September 30, 2010 at 3:32 pm-

Why is it stupid? Are you claiming that you do not have the right to block others emitting EM radiation onto your property? Really? Laser? Gamma rays? Well then I don’t need to argue with you. I’ll just “homestead” gamma radation “patterns”, assert them throughout your apartment and pooof! The issue is gone. And then I’ll take your computer too because it contains “patterns” that I “created”.

Plus, since when does Silas’ opinion that something is stupid fix logical fallacies?

Besides, I did not say that “I believe” in this or that. My arguments are that of a proper falsificationist, I point out errors in my opponents theories without making any assumptions myself.

If you don’t accept those arguments,

Which arguments? Those of you claiming something is stupid? Or did you mean that even though I actually said that indeed it would mean that you have a right to block EM radiation from passing the physical property, that does not count, because … something? You now switched from ignorance to denial?

October 1, 2010 at 2:54 pm

October 1, 2010 at 2:54 pm-

Silas Barta,

Did you not digest any of the arguments I made on this subject the last time we discussed it?

I’ll try and go over it again step by step just in case any of it sinks in this time.The EM problem results from the concept of property being technically incompatible with reality.

Every (and I mean EVERY) action is technically a property rights violation. This is because everything that exists is causally related to every other thing that exists. It is IMPOSSIBLE to perform an action that does NOT interfere with every single chunk of matter in the universe.

The beating of your heart vibrates the entire earth, altering its gravitational field ever so slightly, making tiny alterations to the orbits of the planets and the orbit of the solar system around the galaxy, also slighly altering our galaxy’s spacial relationship to every other galaxy in the universe.So, since all actions are property rights violations, how do we overcome this problem?

We make the assumption that very small violations do not exist. This greatly simplifies the situation and allows society to solve the problem of how to most efficiently utilise its resources.

This is how we are able to talk to each other. The very act of communicating demonstrates that we are ok with the unavoidable physical violation of our bodies (caused by talking) because this violation is so very small.

But there is an unavoidable arbitrariness to this solution. How do we define “very small”? Sure talking is ok, but yelling is often not ok. I consider someone yelling in my face to be a violation of my property rights. So what volume is acceptable? Whatever decision we reach is arbitrary. The problem is very clear in the case of sound waves.

And we also have the problem of two people talking at the same time. The sound often distrupts one another and listeners may not be able to decipher what you’re saying. The norm that has developed in society is that you do not speak while other people are speaking. If you need to interrupt, you often wave your hand or touch them on the shoulder or start speaking in a louder voice with an immediate apology for interrupting.Are there any other areas where the arbitrary definition of “very small” also becomes immediately obvious? Why yes there is. EM broadcasting.

I’m quite ok with you broadcasting radio waves over my property. The violations of my property rights is so incredibly small that I consider them not to exist. I might object if I was running super-sensitive science experiments in my back shed that radio waves would disrupt. But as it happens, I’m not. It seems everyone in society agrees that your radiowave broadcasts are making such negligible impact to their property that they should be allowed to continue. By what if you started gamma radiating everyone’s property in society? I’m sure they’d object. And bright green light? I think people would consider that too big a change too. An arbitrary line, somewhere below red light, has been drawn.Also, similar to sound waves, we have the problem of broadcasts interfering with one another. Let’s look at what is actually happening.

EM waves are different to sound waves or water waves because they do not require a medium. They are energy (with a mass component). They are tangible entities. If I’m broadcasting radiowaves, they belong to me. They are my physical property. I am sending them out into society where they alter other people’s property. But this is ok because the alterations are so small they are considered non-existent. They are on the ‘safe’ side of the arbitrary line.

Now another person sends out radiowaves at the exact same frequency. These new radiowaves, which would normally be considered ‘harmless’, are now causing harm. These new radiowaves are causing a majorly unwanted change in my property. Whether you want to look at it as them altering my radiowaves, or them altering my receiver (which now can’t clearly read my broadcasts) is not really important. What is important is that the first person to broadcast at an acceptable frequency is causing no harm. Each subsequent person is causing harm.The arbitrary definition of a “very small alteration of an individual’s property” depends on the use of that property. I think this is the point that you have failed to take into account.

The first person to broadcast at any given frequency is causing such small changes to the property of others that no property violation is considered to exist. The next person to broadcast at that frequency is causing a large change to another person’s property and this IS considered a property violation. Once one person is broadcasting at a given frequency, other’s broadcasting at that exact same frequency greatly alter the first person’s property, in the context of the use of that property.Now, it should be clear to everyone that none of this has anything at all to do with patterns and ideas. I recall your astonishingly incoherent comeback being something along the lines of ideas being exactly the same as waves. When I tried to point out to you that one does not “broadcast” ideas, that ideas are not physical things that you “shoot” at other people or property, you evaded and ran. This is the first I’ve heard from you since on the subject. And it seems you haven’t learnt a thing!

Your EM argument is dead Silas. You can argue for IP on utilitarian grounds all your want. I have no problems with that. What I have a problem with is you making an argument that you already know to be utterly refuted. Knowing it’s false and then arguing it anyway is nothing more than propaganda.

![]() September 30, 2010 at 12:18 am

September 30, 2010 at 12:18 am

Having worked in a number of high tech start-ups, the liability costs of patents are annoying, but they are small compared to other costs.

The real big one, IMHO, is having a staff of high paid high talent engineers invent something that has already been invented, but that they can’t use because of copyright or patent. Even worse, instead of these engineers aiming to make the optimum design, they aim for the kludge design that has all this odd unnatural ancillary crap in it which may not be optimal, but serves to get around some patent or copyright restriction. Even having things that look like a competitors, or engineers who have seen a glimpse of the competitor code can be a liability. So instead, many places just invent a poorer version of the wheel from scratch all over again. Not to mention, this talent could be used on something so much more productive otherwise, so the opportunity costs are huge.

Also, there are scale costs. IMHO, every vendor having incompatible, non standard, and unworkable parts with every other vendor is not a normal part of a free market. IMHO, in a normal free market, companies would gravitate to standardized interchangeable parts that would be easy to migrate and upgrade. Imagine that there are 100 million cars, and non competitive parts adds $3000 to the price of the car, and non standard parts adds $3000 to the costs of repairs over the cars lifetime, that’s 600 bln with cars alone. Not to mention that planned obsolescence won’t work without patent, because some 3rd party vendor could always come in and undercut. Also, not to mention the disposal and waste costs from the inability to upgrade or repair older models.

There is also a lot of time wasted just making patents that are not needed to provide a service or a product, but to get into a cross license agreement or to use as lawsuit insurance.

![]() September 30, 2010 at 12:04 pm

September 30, 2010 at 12:04 pm

Silas, has someone ever answered you wave question? Someone would have had to, can you do a bullet list of the responses you’ve been given (like we often do about the pro-ip arguments we’ve heard from you etc)?

Someone would have had to of covered homesteading (likely would have covered it every time they’ve responded to your “iron clad” objection) similar to the post above. Are waves physical and cna you control them and “occupy” them? Are wave different than particles that can be controlled and occupied? The right to pollute your own property can be homesteaded, the right to pollute someone else’s property cannot be homesteaded it can only be permitted by the owner. I’m sure theoreticians other than us comment posters have already covered the homesteading of radio waves. Because you have emitted a wave in a particular frequency are you really concluding that no one can ever do that again? My farts vibrate at a particular frequency (actually a range of frequencies), am I stealing from you if my farts are too similar to yours?

The patents are different than homesteading and this is why everyone keeps bringing it up, I’m sure you understand this; you do right? It it that you disagree with homesteading as a means to legitimately appropriate property?

Patents are not homesteading, a patent involves you doing something on your own property (or in your mind) and then filing a paper with the gov to declare that no one in the country to do what you have just done. Even in cases where the other person thought of the idea on their own. I believe it was the telephone that was a perfect case of this happening and software programming yields many more examples where “obvious solutions” are now illegal because someone divined the solution first making the act of solving any programming problem illegal unless you’ve cross checked the full patent portfolio of every other software programmer in the country. Anything less puts every programmer at risk of being a dirty thief without even knowing it (by your definition of IP). You mention you don’t necessarily agree with the current system, is this what you mean? If so then we may have some things in common. Let’s talk about those for a while, then we can put smilies in our posts and avoid name calling

and seriously, that whole mousetrap thing? Are you honestly telling me that mouse infestations were impossible to solve until someone invented the patent system? Then, and only then, did trapping begin? I’m so glad the British brought with them patents to North America. I’m baffled that the Natives were able to catch any food at all without patents to let them invent trapping. What skills they must have had to be capable of doing everything by hand using patent free techniques. But how could they even do this by hand? Wouldn’t they have been thieving the hand use technique?

And further, how many “ideas” are you thieving (by your definition) every time you mention something on this board that a person (live or dead ) has already mentioned? By our moral philosophy this is permitted, by yours it is frobidden.

September 30, 2010 at 4:33 pm

September 30, 2010 at 4:33 pm-

@North: I’ve gone over the argument in sufficient depth here and here.

Note: Stephan_Kinsella “isn’t sure” whether there should be property rights in EM waves. What does that tell you?

September 30, 2010 at 5:33 pm

September 30, 2010 at 5:33 pm-

But what about my farts? and other points?

September 30, 2010 at 5:56 pm

September 30, 2010 at 5:56 pm-

I read your post. You seem to understand the general idea behind wave but you use homesteading too loosely, and incorrectly.

You can homestead the right to do something, but when it comes to the inverse you say in your comments section that you assume away the most critical piece:

“And on the issue of gongs, I was assuming away the nuisance issue. If necessary, assume it’s a special kind of gong that you have to deliberately listen for, which makes it just like radio waves: you don’t hear their content by default, you have to set a radio to decode it (via dial settings).”

The nuisance issue, if properly demonstrated or figured out or however you want to phrase it, is the only way to justify not letting others gong away. If you have a right to have them not gong, it it not because you gonged first, it’s because the their “gonging” affects your physical property in a way you don’t want it to. The only reason you’re allowed to gong in the first place is because you homesteaded the right to do it and affect “unowned” property only. You did not homestead the right if the sound traveled to “owned” property, in that case you need permission or some form of agreement with the owner (e.g. if they don’t care you can go right a head and gong away).

If gonging had a detrimental effect on your health (shakes something loose inside) you have the same leg to stand on. The right at issue here is not who gonged first, it is whether or not the gonging is violating someone’s physical property.

But seriously dude, you response didn’t even answer one of my questions. I asked what others have said about your EM theory not for a link to your EM theory. I was kind of hoping you would summarize what people have told you and then offer a coherent explanation about why you see them as wrong. I don’t know, I thought you’d have an interesting response or something like that. Instead you just copied link to things you’ve said in the past (which it funny because you are criticizing the links posted in the blog entry for being irrelevant; but I find the original links relevant).

My farts are a crude reference but according to your EM theory I am not permitted to do it. What should I do instead?

October 1, 2010 at 9:59 am

October 1, 2010 at 9:59 am-

If you have a right to have them not gong, it it not because you gonged first, it’s because the their “gonging” affects your physical property in a way you don’t want it to.

Wrong — the gonging, by stipulation (that you don’t hear it unless you listen for gongs, to make it like radio waves) doesn’t affect your physical property. Except, of course, in every sense that the (off-property) instantiation of intellectual works “affects” your physical property.

No distinction shown, my case stands.

October 1, 2010 at 11:06 am

October 1, 2010 at 11:06 am-

If that is the case, then there is no justification for someone else to not gong. Do you see the difference here? Let me explain further.

In the case you present there is only one limited possibility justify restricting someone from gonging (I’m saying there is one possibility given the scenario you describe). in your reply here you state that the nuisance factor is not sufficient justification because the gong is imperceptible. This leaves NO justification to restrict someone else from gonging.

Think of this way. If I think of fractional reserve banking and set up shop I will make money begin the only one doing it. Someone can come to town with hoards of gold and offer 100% reserve notes. They are not touching my physical property and they are not even using my idea. They are however “interfering” with my ability to make a buck by “intercepting” my consumers.

Similar to your EM example, there is NO justification for me to restrict someone else from interfering with my consumers like this. I don’t own the customers. My actions caused them at act in a certain way that benefited me and my competitor acted in a way that caused the consumers to benefit him more.

You don’t own the EM waves. You caused them.

Now, the interesting discussion (and here I think you can make a meaningful contribution to theory, just play nice and ask around here for honest critiques to help refine your thoughts as you investigate further) is whether or not air space can be homesteaded and if so, then how can it be homesteaded and owned?

Just like land, you can own the water on your property (under libertarian law, not Canadian law unfortunately) but you cannot own patterns of waves that appear on your water. You can however, tell others not to put waves on your water because you own it, you own the water that sits on your land. In your gong scenario you would need to demonstrate that you own the airspace and others sending waves through it will impede your use of your property (i.e. impede you ability to use your airspace as you planned to use it). You might have a legitimate case here, but it is vastly different than a case for IP.

October 1, 2010 at 11:45 am

October 1, 2010 at 11:45 am-

If you reply to my post above, I think we should be friends (we can still be friends even if we disagree, we probably agree about more topics than we disagree about anyway).

Tell me a little about yourself, where are you from and who’s your favourite author?

I’m Canadian and lately I’ve been enjoying Hoppe’s writing

October 1, 2010 at 11:59 am

October 1, 2010 at 11:59 am-

I’m not interested in chit-chat, least of all with you.

To answer your question, if you see no reason to restrict someone from gonging, then you see no reason to restrict someone from broadcasting radio waves that interfere with an existing broadcaster, so you don’t believe EM frequencies should be ownable.

If you really believe that, that’s stupid, but at least you’re taking a position, unlike Stephan_Kinsella.

I think you have a lot of learning to do before you can explore this topic, as seen in how you just unknowingly showed that you reject EM spectrum rights.

October 1, 2010 at 12:59 pm

October 1, 2010 at 12:59 pm-

“Unknowingly”? I believe I quite consciously took a position on that subject. I even used small words, not sure what tripped you up there. I’ll quote myself “You don’t own the EM waves. You caused them.”

You are an amazing person. That’s all I can say.

We’ll by the sounds of it you have much to teach us oh great Weaver of Raveloe. I will wait patiently in anticipation but pray that my stupidity will not prevent you from gracing us with your superior intellect following future IP related posts.

October 1, 2010 at 1:02 pm

October 1, 2010 at 1:02 pm-

By the way, don’t conclude debates with “If you really believe that, that’s stupid”

Statements like that rank among the least intelligent things you can say in a debate.

I believe we’re done here. ‘Till we meet again.

October 1, 2010 at 1:27 pm

October 1, 2010 at 1:27 pm-

Wow, have to replay a third time. Your errors have some many layers of incorrectness I don’t want to continue but feel compelled to:

“if you see no reason to restrict someone from gonging, then you see no reason to restrict someone from broadcasting radio waves that interfere with an existing broadcaster, so you don’t believe EM frequencies should be ownable.”

I did cite very specific issues. IF you own the airspace then you can restrict others from gonging or EMing all over it. It’s not the EM waves that are owned. It’s the air space. There’s a very clear and concise reason to restrict someone. Again, I see a very clear reason and you conclude that I “see no reason to restrict someone from gonging”

Conversations working toward unanimity among libertarians about what constitutes ownership of airspace are certainly intriguing discussions. Having no present legal recourse for violations the subject is ignored by many, but not all.

I fail to see how you’ve brought up anything relevant about the “a lot of learning” you so proudly conclude I require for me to keep up a conversation.

October 1, 2010 at 2:21 pm

October 1, 2010 at 2:21 pm-

Okay, so you’re a crank who doesn’t believe in EM spectrum rights. Go join the rest of them.

October 1, 2010 at 2:58 pm

October 1, 2010 at 2:58 pm-

And you don’t agree that airspace rights can possibly exist? It can’t be both. EM rights or airspace rights are fundamentally at odds with each other.

Crank is such an unscholarly word, please try a new one. As for you, what alternate word would you recommend I use to describe you for not agreeing that airspace rights can and should exist?

October 1, 2010 at 1:48 pm

October 1, 2010 at 1:48 pm-

Let me see. You don’t mind getting your apartment torched by a laser, your organs degrade by gamma radiation and your eardrums blown by loud music, if they match patterns homesteaded by other people. Because, you know, waves do not affect physical property, so surely the damage is imaginary or unrelated to the “broadcast”.

Maybe you can tell me where you live, I will then send a couple of tips to your neighbours in exchange for pictures.

October 1, 2010 at 2:20 pm

October 1, 2010 at 2:20 pm-

Radio waves, Peter_Surda. Radio waves. Not gamma rays. Not seismic waves. Radio waves.

October 1, 2010 at 2:36 pm

October 1, 2010 at 2:36 pm-

Hmm, so you can only homestead patterns of electromagnetic radiation if they have a specific frequency? And you cannot own patterns of sound waves if the volume is too high? I wonder why? Oh, yes, of course, in order for your theory not to collapse. But rest assured, your burnt decayed deaf body won’t have to deal with that contradiction anymore.

October 1, 2010 at 3:19 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:19 pm-

Silyas, http://www.consumerhealth.org/articles/display.cfm?ID=19990303201129

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bem.10068/abstract

Not agreeing, just pointing out that it’s not an open and shut case.

If they’re proven harmful, do we have any say in whether or not we get pummeled with EM? In the case I presented above the answer is yes, we do have a say. In your analysis the answer is no, we don’t own the waves and have no choice in whether or not we get pummeled with them (only those who own them have a say).

Property rights need to be consistent, not “contingent” on possibly emerging findings about harmful side effects.

October 1, 2010 at 3:25 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:25 pm-

Ionizing vs. non-ionizing radiation guys. Ionizing vs. non-ionizing radiation.

And the spelling of my first name *is* an open-and-shut case, which does not resolve in favor of spelling it Silyas.

October 1, 2010 at 3:55 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:55 pm-

I would not complain about misspelling names if I were you. More importantly though, why is the ionising factor relevant? Electrons moving by conductivity produced by the antenna connected to a receiver are ok, but if they move too far (ionsation) it’s a no-no? I guess it is redundant to point out how you keep making stuff up to cover the holes in your theories.

And how does it affect the issue of music volume?

October 1, 2010 at 3:09 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:09 pm-

I read your ‘gonging’ post, but your understanding of how radios work and how communication works is deeply flawed and thus is coloring your conclusions massively.

The type of ‘radio broadcast’ your thinking of is extremely limited in utility and essentially antique technology. That only allows one-way communication. That is your assuming that one person must be a broadcaster and that everybody else must passively listen to make effective effect use of that particularly useful piece of radio spectrum.

This is indeed how ‘radio’ and ‘television’ broadcasts work, but they are hardly the only form of useful wireless communication and are, very rapidly, becoming completely obsolete.

Your ignoring a very common type of radio… all of the people here are probably using right now:

The digital packet switching network. This is the type of signalling commonly used in things like ethernet and wireless networking as well as many others. Like any technology it was not developed by a single person, but as a gradual evolution of human thought and developments that have cumulated together into modern radio technology.

If you want to see the technical details of how this works then you can take a look at:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ALOHAnetThis sort of networking, instead of depending on a single broadcaster who dominates the particular spectrum, depends on the voluntary protocols shared between a large number of individual devices all of who have the ability to transmit and receive signals at the same time on the same frequencies.

Take a look at a modern coffee shop. You have people with their blackberries, laptops, tablets, netbooks, cash registers, music juteboxes, and a whole host of other devices using ‘Wifi’, bluetooth, and other similar technologies. These things use radios and they communicate on the radio spectrum. Each of them broadcast and each of them receive. All at the same time and all on the same frequencies.

How does this work?

Here is how:

All of them broadcast radio signals whenever they feel like it. That’s it. They just broadcast at random whenever they have something to say. And it works out. Is this magic, is this illusionary?

When multiple devices broadcast simultaneously and they interrupt each other this is called a ‘collision’. When they collide then, obviously, the information is scrambled and of little use. But then they just pick a random amount of time and then broadcast again. The chances of them having another collision is very small.

And this is how it works. They take turns broadcasting, voluntarily according to established protocols that they all agree to, and then they all can broadcast and share the same frequencies with everybody.

Sure there are limits to how far you can push it. With a large amount of radios broadcasting in a small area on different wifi networks you still run into problems. But then people that operate in that area move to different frequencies or use different technologies (such as wired ethernet) so now it’s extremely difficult to find a place were wifi is not still useful.

This is how the tiny amount of microwave spectrum handed to the public to be used freely (somewhat because it was considered largely worthless since there are all sorts of other devices that emit radiation along the same frequency (such as Microwave ovens)) with the least amount of restrictions actually has created the most utility and is the most useful and most valuable portion of the spectrum there is.

A 802.11G network transmits information at about 54Mbps. Out of that about 50% goes into protocol overhead to maintain the system.so you get about 20-25Mbps worth of useful information.

Good quality audio uses about 128Kbps. Talk-show Radio broadcasts can get away with 32-64Kbps without really impacting their ability to communicate and be entertaining and telephony-style encodings can reduce that even further to 8Kbps or so.

So using this approach of voluntarily cooperation and sharing of bandwidth you can have well over a thousand telephone conversations, a hundred music streaming stations, several hundred talk show radio stations, or a few dozen television quality broadcasts. All of which can originate from anybody.

And with newer stuff like 802.11n, Wimax, HSPA, etc etc it’s even faster and more reliable.

Versus exclusive use of a particular portion of the radio spectrum being used for 1 broadcast one-way.

Which do you suppose is a more efficient then? Exclusive use or sharing of the spectrum?

October 1, 2010 at 3:29 pm

October 1, 2010 at 3:29 pm-

@nate-m: You haven’t told me anything true which I didn’t already know.

You don’t seem to get that none of the points you brought up are in any way relevant to my case.

Yes, there are lots of great communication protocols out there. Rockin.

It doesn’t change the fact that the information transmission capacity of radio waves is finite (see Shannon’s Noisy Channel Coding Theorem), which necessitates assigning rights to transmit at specific frequencies and times (even if these vary based on a protocol) once you hit the limit. Hence, there need to be property rights in order for the EM spectrum to be useful as a communication channel.

And if you accept this as sufficient justification for EM spectrum rights, you should regard the isomorphic justifications for IP as sufficient to justify IP rights. QED.

October 1, 2010 at 4:00 pm

October 1, 2010 at 4:00 pm-

Hence, there need to be property rights in order for the EM spectrum to be useful as a communication channel.

No Silas, you don’t. You can use a different demarcation criterion to cover the same scope. You know this, because I explained it to you already. So stop pretending you have an argument and admit you are making stuff up on the fly.

October 1, 2010 at 5:32 pm

October 1, 2010 at 5:32 pm-

which necessitates assigning rights to transmit at specific frequencies and times (even if these vary based on a protocol) once you hit the limit. Hence, there need to be property rights in order for the EM spectrum to be useful as a communication channel.

Well, no. That’s the point. There is no ‘ownership’ of the particular spectrum that is used by Wifi. There are FCC regulations, but those only really limit your transmission power and the frequencies that are free to be used. The rest of everything is decided between the corporations through extensive testing, shared engineering, and contractual obligations.

October 4, 2010 at 1:29 pm

October 4, 2010 at 1:29 pm-

And those are property rights.

![]() September 30, 2010 at 12:05 pm

September 30, 2010 at 12:05 pm

haha “forbidden” not “frobidden”…I don;’t really proof read these things

“It estimates about $31 billion a year as the cost of patent litigation in the US.”

After prohibition was ended, organized crime moved into gambling, prostitution and drugs.

If patents were abolished, the patent attorneys would not disappear. The tick will find another host. The cost will be imposed on another part of the economy.

September 30, 2010 at 1:23 pm

September 30, 2010 at 1:23 pm-

Organized crime only moved into other artifically restricted markets. Much of organized crime DID die after the end of prohibition. Today’s gambling/prostitution/drug crime organizations are much smaller and less influential than the ones back in the days of alcohol prohibition. The goal is to continue cutting off the sources of nourishment and with each successive removal, a number of them will die out. An attorney exists almost purely because the State exists. Just follow where the attorneys go and systematically shut down the corresponding State organization and eventually they’ll all die out.

I have to go now. Silyas it’s been great. We’ll chit chat again next time. Enjoy the weekend

October 1, 2010 at 5:13 pm

October 1, 2010 at 5:13 pm-

That’s inappropriate. I know the spelling is Silas.

Silas, enjoy the weekend.

Silas, LNS weep (but in their own original, independently-created tunes, to avoid theft).