Update: See Are anti-IP patent attorneys hypocrites?, collecting various posts about this topic.

***

My 2010 post on Against Monopoly and my personal site, each generated a good deal of commentary. I’ve reproduced the modified and updated post below, plus some of the commentary from both previous posts.

Update: From Wired 2022: Inside Big Tech’s Race to Patent Everything:

Cisco has regular Patentathons (hackathons, but for patents) and an annual April Fool’s Patent Contest, where engineers are asked to submit “goofy” patents just to see what might come of them. In a Q&A about the event, Cisco’s vice president of intellectual property, Dan Lang, says “the ability to illustrate how employees are able to work on creative, innovative projects alongside inspiring colleagues and managers truly sets a company apart.”

The “Productivity” of Patent Brainstorming

From my comment on Jeff Tucker’s post, A Theory of Open:

Jeff: “Mainly, I think, this comes from an exaggerated reliance on IP and a belief that it is the key to success.”Michael: “Do IP advocates understand that the system may very well make it a better bet to produce patents than products? Why go through the hassle of producing products for finicky customers when you can wait for someone to go through the trouble of making a successful product and threaten to sue them?”

I am not sure if non-practitioners realize exactly what goes on in patenting. Quite often medium to large sized companies hold “patent mining” sessions. They are usually not trying to come up with ideas that they might use in their business. What you do is you get 5-10 engineers to sit around a coffee table, and they are led by a “facilitor” (often a patent attorney). They talk about what they’ve been working on, and try to find little twists or aspects of a design that they can file a patent on. Or, they’ll sift thru a bunch of patents in an area that competitors are practicing in, and just brainstorm, thinking of things they can file patents on. Not because they intend to use these ideas. But just to build up a thicket of patents that they can use against another company, either defensively (i.e., a countersuit if the competitor sues them); or to extract royalties or to squelch competition.

For example, the attorney shows a powerpoint with diagrams from a bunch of patents or product designs. The engineers throw ideas out there. Most of them are ridiculous. Someone is taking notes. One of them might say, “How about if we had two channels of information there, in parallel, instead of one? Do you think competitor B might some day do that? After all, dual-channels are becoming popular right now; they’ll probably have to do this some day.” The patent attorney says, “Say that sounds alright. What’s your name? Bob? Okay, you’re ‘an inventor’. Anyone else contribute to this? Jim, didn’t I hear you say something like, ‘yeah, that might work?’ Okay, you’re the second inventor. Let’s file a patent on this puppy. You each get a $3,000 bonus.”

So, for about 3 minutes of brainstorming, a patent emerges. Maybe a dozen patent applications are filed from that meeting. These are not flashes of genius. They are not sweat of the brow. It’s just a bunch of engineers torn away from their actual design work to brainstorm ways to hamper their competition. So maybe half the patents are abandoned half-way through “prosecution,” a couple years later, after it’s clear even to the bumbling patent office that they are sh*t. Of course about $20-30k was spent on each of the now-abandoned applications, or about $150k. No matter. PTO employees and patent lawyers have to put food on the table.

The other half might finally issue as patents. Most or all of them are probably sh*t too, but now they are issued, and have a “presumption of validity.” Now we’re up to $30-40k or so per issued patent. Got to recoup those expenses and justify the patent budget, eh? And say, it sure looks like company B’s products are … kinda close to the claims in 2 or 3 of the patents. Let’s send them a friendly cease and desist letter.

Company B’s patent attorney is then called into action. He’s hired to draft 3 or 4 “non-infringement opinions” for, say, $30k each. Why? Just in case B is sued, and loses… so that they can at least plead that the infringement was not “wilful”. They still have to pay damages (or stop selling the accused product), but it won’t be trebled… if the judge believes the opinions were “sincere” and “relied on” by the defendant so that, although they were infringing, it was not “wilful” since they were after all following a lawyer’s advice.. .the lawyer they paid $120k to tell them that … they are not infringing … even though it later turned out that they were. No matter, The $6 million B has to pay in damages is at least not trebled $18 million, so that the measly $120k spent on the patent opinions, plus the $1 million spent on patent litigators, was well worth the $12 million saved! B is better off (well, except for the $6 million verdict), its patent attorneys are better off. As for the patentee company, well, their few hundred grand in patent acquisition fees yielded them $6 million, and reduced competition! A win for everyone… right?

This abomination is what pro-patent libertarians thing is just? They think this is compatible with rights and liberty? They think this is productive, innovative behavior? Give me a break.

Update: From comments on AM cross-post:

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:04 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

MLS: “I guess I must be “old school” because I do not recall ever having filed or had filed an application without first conducting a Pre-X search.”

Do you mean you paid an outside searcher, or just your own informal Internet search (which didn’t exist “old school”–did you go down to a local PTO shoebox repository and manually do searches pre-1995?).

It is extremely common for patents to be filed with no search at all. That said, I do searches myself–not a formal one, but the informal PTO type search. But it’s often not done.

“I readily admit that my approach is much more comprehensive than most, but as previously noted I believe the filing of an application is not a matter that should be taken lightly.”

The patent system permits and is rife with junk patent filings. That you didn’t do it doesn’t change this.

Lonnie: “Forget it. Stephan lives in some sort of parallel universe different from ours. I know the number of searches I have done myself is in the hundreds, at least.”

Me, too, probably. So what? How does this prove that the patent system is legitimate? How does this militate against the observation that thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?

“He does not believe in IP, so going to work must be mentally painful. How does someone do a good job when they do not believe in what they are doing?”

This is nonsense. More of the “we will penalize you if you don’t toe the line.” See my posts Patent Lawyers Who Don’t Toe the Line Should Be Punished!; An Anti-Patent Patent Attorney? Oh my Gawd!; Is It So Crazy For A Patent Attorney To Think Patents Harm Innovation?.

It is necessary for my own company to obtain patents for defensive purposes, given the evil monopolistic, protectionist, mercantalist system foisted on us by pro-patent types. Given the system we are in, it is good that my client obtain patents, just as it’s good that a tax victim have a good tax attorney. In a free society neither patent lawyers nor tax attorneys would exist.

“Of course, he also believes in filing junk patents without doing a search. Weird.”

It’s not that I “believe in it”, it’s that I believe that it is commonly done. I don’t believe in taxes either, but I believe they exist. Notice that MLS above did not deny that this is done.

“As for your comment about the way patents were meant to be used, no, you are wrong. They were meant to communicate to the world an invention and the recognition that the right to make, use, sell or offer to sell the invention was given to that inventor for disclosing the invention to the world.”

How do you know what they “were” “meant” to do? We know that the statute gives the patentee a right to extort and sue. And it’s predictable that if you dish out this right, people will take and use it. Surprise, Marshall Texas is prospering!

“However, some people, apparently those in the companies you have worked, have twisted this to be a weapon of ambush.”

SHOCKING!!

“Fortunately, the laws are changing so that such ambushes are harder and harder.”

Nonsense. The law is not changing fundamentally. See my Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way. Patent shills squeal like scalded dogs when they sense any potential dilution of patent “strength.”

“Also fortunately, statistically less than 1% of all patents are treated in this way, and far less than 1% of all patent holders act in this way. I would also remind you, Stephan, than there is no such thing as an evil system, only evil people and evil actions.”

It is evil for the state to hand out legal monopolies to people, that they can use to extort, sue, ruin in the state’s illegitimate courts.

Lonnie: “Actually, it is more akin to being a priest while being a devout Satanist. The conflict must be tremendous. I am curious as to how one does something well that one does not believe in, or believes is morally wrong? I would think Stephan would give up being a patent attorney and just be a plain attorney, or perhaps an engineer, if he can, of course.”

My career is none of your business and is irrelevant to my case that IP is illegitimate. Of course patent shills would love for any patent attorney to toe the line and for those who don’t to leave the profession so that they can tar and feather any opponents as being ignorant of the workings of the system they oppose. Too bad, podnah.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 09:05 PM by Stephan Kinsella]

[Comment at 01/17/2010 10:17 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

In my post above, I tried to just mention one aspect of the real patent system–to show that it’s not this idealized system that laymen are led to believe. They–and many libertarian IP advocates–have this romanticized notion of the patent system. They think of it as the just reward given to the diligent inventor toiling away for years to produce some amazing, insightful, flash-of-genius, clever contraption that we would not have without his effort. And yet, as noted above, probably less than 1% of all issued patents even remotely qualify for being classified as this type of invention. The vast majority of patents are junk of one type or another: they are trivial; or obvious if we could only find enough art (or if the examiners were competent; or the standards for obviousness were objective); or duplicative; or represent innovations that already exist, or that others “skilled in the art” would come up with in the course of designing products that meet current market demands. This whole patent system is nothing but a mercantilist grant of monopolies that saps and transfers and destroys wealth for the benefit of privileged classes, and is tolerated by the masses because they do not understand the system and place unjustified trust the power-regime elite.

So a few patent agents and attorneys weigh in (also on facebook here), not to mention shills like Gene Quinn and Dale Halling, with either cruddy arguments (Halling and Quinn) or irrelevant, off-topic points. They say that I am wrong to imply that there are patent mining sessions, junk patents, etc.–oh no, why, a search has to be done and a careful review by the attorney. When I say no, searches are not always done, they claim that it’s routine and “old school,” to imply that I’m lying or don’t know what I’m talking about. They assert that it’s good practice (which I never denied) and that I must now know this. I usually do searches; in my practice I recommended them often esp. in the case of an independent or small inventor. But I have been around enough to know it’s not always done and while some companies do it routintely others have a policy against it. Some small-time or part-time practitioners who have only represented a few small clients or worked at one company that happened to emphasize searching might not be aware that it’s not always done that way; but all this is irrelevant. The system permits it; searching is not always done; and patent attorneys howl with outrage at proposals to require searches. And even if they were required it would not improve quality overmuch.

They imply that they have never heard of these patent mining sessions I speak of. Gasp, it’s just not done! Nonsense. Many companies push inventors to submit disclosures–they pay them thousands of dollars in bonuses to incentivize this–and for many of companies it is, at least in part, at least a numbers game. It is very common for a weak application to be filed just to see if even a narrow patent is issued–hey, maybe it’ll slip by the examiner. And it “counts” as another patent on our stack, don’t it? We all know that the patent standards of obviousness and novelty are ambiguous, non-objective and vague; that it’s not possible to be sure you have found all the relevant prior art; that the PTO is just an incompetent government bureaucracy (in fact it’s widely observed among patent lawyers in the US that the European patent examining corps. is (for some reason–maybe because it’s in Germany) much more competent than the US one).

As for the ridiculous contention that patent mining sessions as I describe are the stuff of fantasy—I’m loath to have to even go through the tedious work of demonstrating what is widely known in the patent bar but, sigh, okay. Here are just a few I dug up with easy searching in my own files.

Take for example a patent strategy book I have, Stephen Glazier’s Patent Strategies for Business (I have an earlier edition; the current one is here). Just skimming its table of contents gives one a taste of the wide variety of strategies companies and their patent professionals engage in—most of them are quite obviously market distorting, protectionist, extortionist, and so on.

For example, Chapter 1 lists “Five goals of patents”:

- Protection of a Company’s Products, Services, and Income

- Generating Cash by Licensing Patent Rights to Others

- Obtaining a Legitimate Monopoly for Future Exploitation

- Protecting Research and Development Investments

- Creating Bargaining Chips

Chapter 3 is “Invent Around your Competitor’s Patent (and the Antidote), and Other Patent Strategies”, and covers, inter alia,

- The Picket Fence Strategy

- The Toll Gate Strategy

- The Submarine Strategy: Old and New

- How to Submarine a Picket Fence

- The Counter-Attack Strategy

- The Stealth Counter-Attack

- The Cut Your Exposure Strategy

- The Bargaining Chip Strategy

Chapter 4 teaches you how to “Prevent Product Re-Use With Patents,” and Chapter 7 has topics such as “Three Practical Tips: 1. A competitive Advantage” and “Due Diligence as Industrial Espionage.” Chapter 9 discusses “Patent Litigation As A Business Tool.”

Do these corporate shenanigans sound like the kind of creative, innovative activity most people have in mind when they think of the patent system?

And of course there are various methods companies employ to drum up invention disclosures. From p. 3:

A Nine Step Program

Developing a strategic intellectual property management program can be accomplished in nine basic steps. The following discussion focuses on patents, but analogous steps apply to copyrihts, trade secrets, confidential information, and trademarks.

1. Obtain Disclosure of Inventions. One effective way for some companies to encourage employees or consultants tp disclose their ideas for inventions is to offer a program of cash incentives. This is typically a one-time payment or a regularly paid percentage of the income resulting from an invention. In some companies, patent disclosure forms are distributed periodically as a way of soliciting useful ideas regarding inventions.

Another effective method has been for patent counsel to meet with a company’s technical people to ferret out together innovations that may yield patents of value in the marketplace. It can be particularly useful to do this with a focus on a new product or service just before its market introduction. With companies with a particular intense product development schedule, scheduling regular monthly meetings of the sort can yield good results in identifying important opportunities.

Glazier’s advice is very good—he is talking about how to exploit, use, and navigate this artificial, state-created mercantilist system.

Such techniques and strategies are widespread. That’s one reason companies have in-house patent departments and hire outside patent law firms. For example, one presentation of services a patent firm was pitching to me included:

Recommended patent strategy:

- Analyze current/future business directions

- Identify targets

- Identify defensive risks

- Develop patent portfolio management strategy aligned with business strategy

- Tune your claim drafting strategy to your business objectives

Another part of their presentation, on “Harvesting and Mining Invention Disclosures,” listed these services:

Harvesting

- Train management and engineers with written materials

- Lead Blue Sky and disclosure harvesting sessions

Another service is “Portfolio Analysis For Licensing/Assertion

“.

Another patent attorney I know of has what he calls a “market-domination approach to patent law”.

Another book is Strategic Patenting, by Robert Fish (I have the pre-publication version): it covers topics such as

I. B) Cost-Effective Patenting Produces The Broadest And Strongest Patents. (1) Focus On Patenting As A Critical Component In Defining Goals And Resources.(2) Choose The Market With Patentability In Mind [NSK: obvious market distortion caused by the patent system]

(3) Target Patent Strategies To The Choke Points [NSK: protectionism…]

As for ginning up invention disclosures, the book has this section:

II. B) Gathering Information • (1) Invention Disclosure Forms (Memos of Invention) • (2) Information Gathering Discussions

Some elaboration from the text (of my draft copy):

(1) Information Gathering DiscussionsThe lazy-man’s way of drafting a patent application is to have the inventor draft a lengthy disclosure, and then beef up the disclosure with a few claims. Don’t do that. That process almost always results in bad patents.

The better practice is for the patent attorney to (a) discuss preferred embodiments with the inventor in considerable depth, and then (b) go on to brainstorm alternative embodiments with the inventor. My experience is that the patent attorney should obtain a brief understanding of what the inventor thinks he invented, conduct a search of the field, and then have a lengthy discussion with the inventor to identify the scope of the invention. Shorter discussions can then be used as follow up on particular points. The lengthy discussion is usually needed because it takes awhile, sometimes an hour or more, to guide the inventor into a mental state where he is focusing on possibilities rather than preferences and actual embodiments.

The process can be rather uncomfortable for inventors. It is difficult to get the inventors to help us brainstorm the outer edge of the invention. They typically say “this is what I have invented,” and hold up their drawings or model of a preferred embodiment. When I ask how the embodiment differs from what is known in the field, they usually say that it is unique – that no one else has solved the problem in the same way they have. Well that doesn’t help us at all. I can’t claim a “unique” device. I need to know how the device is unique. I need to identify what is the smallest subset of elements that distinguishes what the inventor thinks is his invention from the prior art.

One strategy I have employed successfully with research companies is to gather together several researchers in a room for a morning, afternoon, or even an entire day. I start the meeting by identifying problems in a field of interest, and then take suggestions on what is needed in that field. To focus the group on an interpersonal level, it is usually very helpful to have a marketing person in the room, and engage the researchers in a tête-à-tête with the marketing person. The goal is to stimulate thought on what can be claimed in a patent application that would provide the company with a competitive advantage, and then work backwards to figure how those goals can be accomplished. Typically the problems are quite difficult to solve, and the solutions proffered at the meeting are only minimally practical. But I try to classify the solutions in some manner, and then figure out how to describe the classes of solutions. As long as I can conceptualize one member of a class of solutions, I can usually claim the entire class. I then go back to the office, run patentability searches on the classes of solutions, and begin drafting claims. If the claims seem broadly patentable, and useful to the company, I then go back and work with the inventors to run experiments that provide examples that support the broad claims. A good meeting usually produces half a dozen or more patentable inventions.

Yep—inventions created during the meeting, on paper only. No working models, etc. N.B., I am not criticizing Fish at all; his advice is professional and competent. These are rational responses and ways to navigate the system Congress and its corporate allies have foisted on us.

And here are some routine comments I found in some patent mining materials I have, in a book review:

“Whether patented ideas will ultimately help or hinder innovation is still under debate (see Owning the Future). In Rembrandts in the Attic, however, authors Kevin Rivette and David Kline get down to business, offering practical advice for competing in today’s intellectual property arena.

Their advice ranges from the simple to the sublime. First, they suggest, take stock of the patents you already own. Many companies are sitting on unused patents that could be worth millions. For example, IBM licensed its unused patents in 1990, and saw its royalties jump from $30 million a year to more than $1 billion in 1999, providing over one-ninth of its yearly pretax profits. And if you can’t find buyers for your unused patents, then look for companies that are infringing upon them–companies that might owe you a piece of their profits. Rivette and Kline offer “patent mining” techniques to spot such potential infringers that can also reveal where your competitors are headed and help you get there before they do. Overall, Rembrandts in the Attic is a crafty and practical guide for companies that may have untapped riches in storage. –Demian McLean

Fish’s book also goes into other strategies:

(1) Choose The Market With Patentability In MindA thorough goals/resources analysis invariably leads to a number of different markets that can be attacked. The question is, which ones should be chosen and which ones passed up. Here it is useful to map out potential growth of different markets with respect to the degree of patent protection available. In the chart below growth is mapped against patentability. The best markets are those that have both high growth and are open to patentable subject matter. High growth markets where there is little chance of securing broad patent protection will likely be inundated with competition. An example might be the wheelchair market. There will certainly be an increase in market as the population ages, but there are relatively few patentable improvements that are likely in that field. Unless there are other barriers to entry, the product will be subject to commoditization, and the margins will be weak. Markets where broad patents are likely, but have little chance of growth, will have good margins but weak sales. In this category I might find an invention that helps window washers handle work in high rise buildings. No matter how great the invention is, the market is likely to be extremely limited.

Figure 11 Choosing The Market Based On Growth And Patentability

(2) Target Patent Strategies To The Choke Points

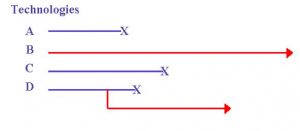

Once a market is selected, the next step is to figure out where the choke points lie. Consider the market below, in which there are four dominant technologies, A-D. Here a contemplated patent portfolio would effectively block or render technologies A and C obsolete, but have no effect on technology B. Technology D is also blocked, but a derivative technology circumvents the patent. This market is probably a poor prospect for a new entrant. The contemplated patent portfolio, even if it could be obtained, would fail to secure a dominant position for the patent holder.

All of this, of course, harkens back to the original goals with respect to dominance in the market. An applicant can be very successful being niche or merely significant player.

Figure 12 Target Patent Strategies Based On Choke Points

The patent system encourages companies to seek state-granted monopolistic protectionism.

Again, such strategies are common. How patent practitioners can deny all this with a straight face is beyond me. From the table of contents of another book on my shelf, “Strategic Patent Planning for Software Companies: A Look at Some Current Patent and Licensing Strategies at Both Ends of the Software Spectrum: Microsoft and Apache,” by Eric Stasik (2004), for example:

The Strategic Patenting Objectives of Software Companies3.1 The Business Needs of Software Companies

3.1.1 Technology Exchange

3.1.2 Near-Term Competitive Protection

3.1.3 Litigation Avoidance

3.1.5 Royalty Income

3.1.6 Out-License Technology to non-Competitors

3.1.7 Acquire Complementary Technology from non-Competitors

3.1.8 Minimize Royalty Payments to non-Competitors

3.1.9 Product Clearance

3.1.10 Promulgate Open Standards

3.1.11 Promote Interoperability

3.1.12 Deter the Development of Alternative Technologies

3.1.13 Strengthened Position in VAR and OEM agreements

3.1.14 Preserving Future Options

Again, we see what the patent system is really for: it’s protectionisn; it’s to generate income, by extorting it from other companies by the threat of litigation; it’s to cross-license with other big companies: the cost is the patent attorney fees they have to pay to acquire their patent arsenal, but the advantage is the erection of a huge barrier to entry because small and new players have little defense against the patent threats.

***

Comments from the StephanKinsella.com thread:

Dale B. Halling January 8, 2010 at 10:27 am [edit]

-

Stephen,

Adam Smith considered the division of labor as one of the most important methods of increasing a nation’s wealth. Without a strong patent system, many talented engineers, scientists, and inventors waste their time on playing politics and honing their management skills instead of focusing on inventing. Only by playing politics and becoming managers can these people increase their income. Since we know that technological innovation is the key to real per capita increases in income (see Robert Solow who won the Nobel Prize in economics for showing this), we want a system where talented inventors focus on inventing. Despite your cynical portrait of the inventing process, a company that focusing on inventing, as opposed to production, is similar to what a University does. Dolby is a company that has focused on inventing instead of production. Dolby has been a major benefactor to the audio industry and the economy. Qualcomm is a company that focused on inventing instead of production. As a result, they have been able to create the technology of CDMA for cellular telephones. Without a strong patent system Dolby’s business model would not be possible.

As the U.S. changes from an industrial economy to an information economy, more people will need to be employed in the processes of inventing instead of production. How exactly are these people going to be compensated for their efforts without a patent system?

Dale B. Halling, Author of the “Decline and Fall of the American Entrepreneur: How Little Known Laws and Regulations are Killing Innovation.” http://www.amazon.com/Decline-Fall-American-Entrepreneur-Regulations/dp/1439261369/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1262124667&sr=8-1

Paul Vahur January 9, 2010 at 5:49 pm [edit]

-

Mr. Halling, you ought to read Against Intellectual Monopoly by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine. Also available at Amazon. It answers how innovation can and has taken place absent the patent system.

Stephan Kinsella January 9, 2010 at 5:54 pm [edit]

-

Paul, Halling has no reason to read Levine/Boldrin, since he doens’t care whether his arguments are right are wrong. He is a patent lawyer, just a shill for the system, trying to mount a justification for his profession’s existence. He is making lawyers’ arguments, not trying to–or concerned about–truth.

Dale B. Halling January 11, 2010 at 10:25 am [edit]

-

Here are some basic rules of reason that you might want to consider.

Occam’s Razor: The simplest explanation is most likely correct.

Hume’s Corollary: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Property Rights: In every case it has been tested, property rights result in increased productivity out of the asset. The Pilgrims almost were starved to extinction by ignoring this rule.

Patents are property rights, they are consistent with the historical basis for property rights – namely Locke’s labor (mental and physical) theory of property rights.

Those countries with the greatest amount of technological innovation and technology diffusion have patent laws. These countries are also the richest in the world.

But somehow the anti-patent crowd expect us to ignore Occam’s razor and fails to provide extraordinary evidence for their extraordinary claim. This is not reason, it is not scholarship, it is cynicism or theology.

Stephan Kinsella January 11, 2010 at 10:41 am [edit]

-

Halling:

Here are some basic rules of reason that you might want to consider.

Occam’s Razor: The simplest explanation is most likely correct.

Hume’s Corollary: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Property Rights: In every case it has been tested, property rights result in increased productivity out of the asset. The Pilgrims almost were starved to extinction by ignoring this rule.

Patents are property rights, they are consistent with the historical basis for property rights – namely Locke’s labor (mental and physical) theory of property rights.

Occam’s and Hume’s rules are not applicable to the normative case. And even if they are, they would imply that the burden of proof is on you, who support the extraordinary claim that the state–the most murderous, evil, inefficient agency ever known to man–can actually enhance overall social welfare by handing out state monopoly privileges. What is your evidence? That you think America has been a success since its founding, and since our founding we’ve had IP law. This is among the shoddiest reasoning I’ve ever seen. If you have a proof that the patent system is an overall or net benefit, let’s see it. All you need to do is provide evidence that shows conclusively that the patent system is worth it overall. Such a study would need to show (a) the costs of the patent system, in dollar terms, (b) the benefits of the patent system, in dollar terms, and (c) the net difference, presumably positive. I’ve assembled the large number of studies I’m aware of; none of them concludes this. See: Yet Another Study Finds Patents Do Not Encourage Innovation.

Those countries with the greatest amount of technological innovation and technology diffusion have patent laws. These countries are also the richest in the world.

They also have a mafia, a tax system, antitrust laws, and anti-drug laws. Are those things also conducive to economic growth? Is correlation causation in your mind?

But somehow the anti-patent crowd expect us to ignore Occam’s razor and fails to provide extraordinary evidence for their extraordinary claim. This is not reason, it is not scholarship, it is cynicism or theology.

Your comments betray the scientism and lack of familiarity with ethical reasoning typical of engineers (see my various posts on the limitations of the scientistic engineering mentality here). You are doing what typical engineers do: trying to cram the philosophy of science by brute force into your scientistic categories, trying to reinvent the wheel with limited tools. We all have values and norms, and they are not all “theology”. You yourself seem to be in favor of the patent system–this is a normative position, not a merely factual one. Your reasoning in turn rests on more basic norms. By your own “reasoning” this is some religion of yours too. Your crude attempts to “reason” using Occam’s razor are really embarrassing. If you really want to inform yourself before spouting off on such topics read Mises’s Ultimate Foundations of Economic Science or Hoppe’s Economic Science and the Austrian Method.

First can you safely take a levitra along with a penile injection March 8, 2010 at 10:58 am [edit]

-

Best Wishes, Real how long does hydrocodone stay in the bloodstream[url=http://mag.ma/howlongdoeshydrocodon#1]Real how long does hydrocodone stay in the bloodstream[/url], 359, Cheap prescription and consultation online for adipex[url=http://mag.ma/prescriptionand#1]Cheap prescription and consultation online for adipex[/url], =]], how long does hydrocodone stay in your system free [url=http://mag.ma/howlongdoeshydrocodone#1]how long does hydrocodone stay in your system free[/url], 7306, discount viagra furthermore cheap adipex reviews[url=http://mag.ma/discountviagrafurthermore#1]discount viagra furthermore cheap adipex reviews[/url], geafj, can you safely take a levitra along with a penile injection online[url=http://mag.ma/canyousafelytakealevitra#1]can you safely take a levitra along with a penile injection online[/url], 19734,

***

From the Against Monopoly thread:

[Posted at 01/07/2010 09:51 PM by Stephan Kinsella on Patents (General)  comments(73)]

comments(73)]

Comments

Engineers being invited to think up ways of hobbling the competition is like doctors being invited to think up non-lethal ways of ‘persuading’ terrorist subjects to confess, but at least with the latter it’s a bit more difficult to get those ways registered with a ‘this is not torture’ registry as legally protected, e.g. filling lungs with water.It should sadden all engineers to think that some of them would stoop so low as to assist the patent miners in their highly unethical pursuits.The patent office is something Dan Brown would dream up as a papal conspiracy to prevent technological progress at all costs by scouring the world for every novel idea or design that anyone can think of precisely to prohibit anyone using it (apart from the filer, as their reward), thus holding back technological progress as much as possible in order to extend the duration of the Catholic church’s theological hegemony.

Aside from the ‘right thing to do’ of abolition, the only other solution that presents itself is to facilitate the equivalent of file-sharing for patents, i.e. let the public flout its own laws supposedly enacted in its interest.

This would be where product manufacturers disintermediate themselves from patent infringement to delegate that crime to sacrificial proxies and the public, e.g. fly-by-night companies that are created per bulk order. 10,000 customers procure the manufacture of an infringing device from the patent infringing proxy company that sources all non-infringing components to assemble into a patent infringing device to be immediately dispatched to the customers (who in turn install any patent infringing software they obtain from file-sharing networks).

There is thus no time for the ‘competing’ patent trolls to get their act together and hold the patent infringer to ransom, because they’ve gone. The only ones left to sue are the public with their patent infringing devices. Good luck suing them for having the gumption to procure the manufacture of patent infringing devices without a license.

[Comment at 01/08/2010 01:45 AM by Crosbie Fitch]

[Comment at 01/08/2010 02:08 AM by Crosbie Fitch]

[Comment at 01/09/2010 03:47 PM by MLS]

[Comment at 01/09/2010 05:07 PM by None Of Your Beeswax]

[Comment at 01/09/2010 08:29 PM by MLS]

Wow, two pieces of bullshit in one article.First, I have seen people on this site who have again and again said that engineers never read patents. Now, you are saying that they do? Which is it? It cannot be both ways.Second, statement without proof that “quite often” medium to large size companies hold these sessions where a bunch of engineers sit around and come up with potentially patentable ideas with no intention of marketing them. I have to see proof for this unsupported allegation. I have been in medium to large size companies, including having been in charge of an engineering department, and I have never participated in one of these kinds of sessions.

I guess anyone can make up anti-patent stuff and then have their sycophants kowtow to the brilliance of their fiction, treating it as gospel.

Nice religion you have here.

[Comment at 01/09/2010 08:50 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

[Comment at 01/09/2010 10:01 PM by None Of Your Beeswax]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 03:38 AM by Samuel Hora]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 05:12 AM by None Of Your Beeswax]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:04 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

Earwax:Liar, I was not the “PHB” of the engineering department and I am not a patent attorney. Leave your insults for lawyers, not engineers.As for who has to prove what, the statement was made without a SINGLE FACT to back it up. If you want unsupported allegations, I suggest that Against Monopoly has become a joke because the posters have come full circle, accusing people of doing things they already claimed they did not do.

Samuel:

Wrong. In fact, the company that WOULD do this is more than stupid. First, how do you know the field unless you review prior art? If you did not review the prior art, then you are spending hundreds of thousands of dollars with little or no likelihood that you would get a return as prior art from the internet, articles and patents shoot down application after application. As any competent patent attorney or agent will tell you, the starting point for determing whether you should file a patent is the state of the prior art. Then the second point is the value to the company. Filing a bunch of patents with the hope that one of them sticks is not only an unlikely business model, it is a ridiculous business model. I cannot see anyone in any successful medium or large sized company doing such nonsense, and have never seen a documented case of where such companies did so, except on an infrequent basis. Of course, there was one Enron, but how many other companies emulated their insane business model?

Stephan:

You mix up issues that cloud the original post. Let’s stay focused.

You ask how I can deny that “such patenting goes on”? I will do not deny that there may be a company out there that does such. I have seen a couple of posts on Techdirt that allege such behavior. However, I note that those posts were regarding teeny little companies, not medium or large size companies. I demand evidence that “Quite often medium to large sized companies hold “patent mining” sessions” where someone throws up a Power Point slide and then does a bunch of brainstorming to come up with ideas (not inventions) that are then filed for patents. Absurd. Even the one group of people who were alleged to have done this have thus far not been successful in obtaining a single patent.

As for the “13 minute” disclosure, as you well know, the “13 minute” disclosure generates searches, analysis, and ultimately a business decision as to the value of any disclosure. That such disclosures (not as a result of the alleged “patent mining” sessions, I note you said) are filed, undoubtedly, but these are not the results of mythical sessions where a bunch of ideas are generated as the basis of valueless patents. These same disclosures will also be dealt with as any other garbage – it ends up in the land fill.

If someone is going to allege absurd behavior, at least make it plausible. File this one under Libertarians as Standup Comedians.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 08:50 AM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Lonnie: “As for the “13 minute” disclosure, as you well know, the “13 minute” disclosure generates searches, analysis, and ultimately a business decision as to the value of any disclosure. That such disclosures (not as a result of the alleged “patent mining” sessions, I note you said) are filed, undoubtedly, but these are not the results of mythical sessions where a bunch of ideas are generated as the basis of valueless patents. These same disclosures will also be dealt with as any other garbage – it ends up in the land fill.”Lonnie, I’ve prosecuted hundreds of patents. I’ve seen their quality, and how they are produced. I don’t think you know what you are talking about. Disclosures rarely generate searches and analysis. Quite often NO search is done (it’s not required, and a good one is expensive). What happens is you just file it, and the filing fee pays the PTO’s examiner to do his own search. If he comes back with killer art, you might abandon it then. And sure, there’s a business decision but it’s not always based on the value of the invention–do you realize that lots of crap patent apps get approved? It’s like throwing spaghetti against the wall: some of it sticks. If you have a stack of issued patents, so what if 2/3 of them are crap? They still exist; they have a presumption of validity; and they take lots of money and time for your competitors to analyze. If I know XYZ company has 1300 patents, do you think I’m going to pay $17 million to a patent lawyer team to spend 3 years analyzing them all? You have got to be kidding. No–what I’m going to do is build up my own portfolio to use defensively if they sue me. Or, if A and B enter into cross licensing, and A has 1500 patents and B has 300, they don’t analyze them all–but B might have to pay some cash in addition to its 300 patent license just by counting patents.Why laymen feel compelled to weigh in on such matters is beyond me.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 09:26 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

Our resident troll writes:”[insult deleted]:[calls me a liar]”

No, you’re the liar and the cerumen.

None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

“As for who has to prove what, the statement was made without a SINGLE FACT to back it up.”

The person who called everyone here a liar (and me twice) is the one with the burden of proof.

Stephan Kinsella writes:

“Lonnie, I’ve prosecuted hundreds of patents. I’ve seen their quality, and how they are produced. I don’t think you know what you are talking about.”

I’m afraid that Lonnie knows exactly what he is talking about, and is deliberately lying. He mentioned on this site, months ago, that his own work depends on patents in some way, implying that he was a corporate patent attorney. So if he really IS ignorant about these matters, then he is also incompetent in his job. (Insecurity, whether due to obsolescence or due to incompetence, would go a long way towards explaining his attitude problem, in turn.)

[Comment at 01/10/2010 09:57 AM by None Of Your Beeswax]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 09:59 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

SK,Mister Holder is not a lawyer or agent. He is solely an engineer who has worked primarily in the mechanical arts.I am a lawyer, and one who has been working in this area in both private and corporate practice for many years.

In private practice it was not uncommon to have disclosures thrown over the transom for an application to be prepared. In each instance I would personally contact all persons concerned (inventor(s), supervisors, attorneys, etc.) to try and figure out if what has been disclosed is really something important to the their current and/or future business plans. If important, and once I was thoroughly grounded in why this was so and advised on the pros and cons, only then did I move forward. In a significant number of cases applications of inventions(s) were never filed because there was no good reason to do so. It would have been a waste or time and money resources.

In corporate practice, and as counsel to a Fortune 20 company, I made it policy that only truly “important” were considered for filing. R&D dollars were carefully allocated based upon near and long-term business plans, and my primary objective was to make sure that participants in any decision-making process knew the ground rules and applied them consitently. In fact, one of my first acts as counsel was to dismantle all “review boards”, which I view as silly, unproductive, and of virtually no value for some of the reasons you state, and took my cue from lead functional VPs, Directors, Managers, and Supervisors who really knew what was important and what was a trinket. Those considering disclosures were the only ones making initial recommendations, and I served in the capacity as counsel and honest broker.

As a consequence only a very few disclosures ever ended up as a patent application, and even then I would immediately pull the plug on applications and patents as changed circumstances dictated.

In attempting to generalize your personal experience as somehow indicative of the process as a whole in my view demands much more than mere hand waving and caustic comments.

When I first began private practice my mentor, an outstanding lawyer and true gentleman with a large firm in Chicago with he had practice for over 40 years taught me the imperative of providing value-added service versus mechanically responding to whatever was presented to me for action. I took his advice to heart and it has well served clients I have represented over my 31 years of practice.

Just because a minority may proceed without thinking about what I view as incredibly important consideration is no good reason to suggest that laywers prone to practice in “cruise control” are the norm and not the exception.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 11:04 AM by MLS]

@Kinsella: and so is he. Loath to admit it, that is.MLS writes:[calls me a liar]

No, you’re the liar.

None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

Lonnie himself implied he was in the patent business.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 11:27 AM by None Of Your Beeswax]

NOYB,You must have me confused with another commenter. Easy to do given the format of how comments are posted here.MLS

[Comment at 01/10/2010 02:49 PM by MLS]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 02:52 PM by Stephan Kinsella]

Stephan:How interesting, regarding your prosecution of hundreds of patent applications. As a matter of fact, so have I. Indeed, depending on how long after you became registered that you started prosecuting patents, you and I may have started prosecution at approximately the same time.Now, a bit of clarity for all concerned. I am a registered patent AGENT, and have been one for about six and a half years. Prior to becoming registered, I was writing applications, doing searches and drafting office action arguments for nearly a decade before I became registered. Of course, Stephan you would have known that being the highly competent attorney that you are with hundreds of applications under your belt and thus knowing exactly where to find that information.

Stephan: Regarding searches. You and I both know, with our hundreds of applications of experience, that you do not have to analyze every single patent from a competitor, nor is there usually value in doing so. Of course, your hyperbole makes for great sarcasm and a subtle insult. Do not bother to quit your day job and do standout.

Stephan, I am unable to speak to the process that you have observed. Considering all you have said, it is no wonder you are disillusioned being a patent attorney. I would say that the vast majority of disclosures I have been involved with have involved a search and an analysis. How would you know whether you are wasting your client’s money otherwise? Of course, if your client has deep pockets and loves the “hail Mary” philosophy regarding patent application filing, well, slipshod way to run a ship in my personal opinion. If that is truly what you have seen, then I can understand everything you have said and your unhappiness with being a patent attorney. However, I would not work for such a bizarre organization that focuses on junk patents. I have never personally seen such an organization, and you are the first attorney who (probably because of your disillusionment) has admitted for working for such a organization.

As for my “ignorant” comments, I will refrain from commenting on your ignorance as to how patenting works in real manufacturing companies. When you would like to know how companies that make real products file for and use patents, send me an e-mail. Maybe you could come visit me in Indiana and we can show you how a real company does IP versus whatever patent mill you have been working for.

As for MLS’s comments, they are similar to the experiences I have had. Note that MLS clearly indicated that just about EVERY (and maybe all) patent applications had some level of analysis and review, even if it was just himself and a business person. I am guessing that some of that the applications involved got a lot of searching to be sure there was some value. I am also guessing that MLS worked for a real company that actually produced real products, or a firm that worked for real companies that produced real products, rather than just junk patent applications of dubious value, hoping that one of them would “stick.”

Indeed, Stephan, the thought that you participated in such activities just astounds me. Why not find a company or firm that uses patents the way they were intended? There are tens of thousands of such companies, as opposed to the places you have somehow had the bad fortune to be employed.

Earwax:

Let me see. You called me an attorney. I am not. Therefore, that was a lie. Thus, you are a liar. The facts speak for themselves. Do not bother to deny what is quite clear from your comments above. You have said other lies, but I only need one for evidence.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 05:04 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Lonnie:”Of course, Stephan you would have known that being the highly competent attorney that you are with hundreds of applications under your belt and thus knowing exactly where to find that information.”Yes, it’s easy to look up the roster of registered agents and attorneys. So what?

“Stephan: Regarding searches. You and I both know, with our hundreds of applications of experience, that you do not have to analyze every single patent from a competitor, nor is there usually value in doing so. Of course, your hyperbole makes for great sarcasm and a subtle insult. Do not bother to quit your day job and do standout.”

I think you mean standup. I htink the reason you don’t analyze them is because it’s impossible. As to there being no value to it–well, given that we are charged with notice of issued patents, why wouldn’t there be value?

“Stephan, I am unable to speak to the process that you have observed. Considering all you have said, it is no wonder you are disillusioned being a patent attorney.”

I’m not disillusioned about it. I came to my views for purely principled reasons, as I’ve laid out.

“I would say that the vast majority of disclosures I have been involved with have involved a search and an analysis.”

I doubt it. And anyway, so what? That the patent system permits and incentivizes this, is part of the problem.

“How would you know whether you are wasting your client’s money otherwise?”

How would you konw? You get them issued, and you are paid. Off on your way!

And patents are useful to companies even if they didn’t have a search and anaysis first.

“Of course, if your client has deep pockets and loves the “hail Mary” philosophy regarding patent application filing, well, slipshod way to run a ship in my personal opinion.”

So what? The patent system permits it.

“If that is truly what you have seen, then I can understand everything you have said and your unhappiness with being a patent attorney.”

I have policy views about patents grounded in libertarian views about property rights. It’s not about a disgruntled patent attorney.

“However, I would not work for such a bizarre organization that focuses on junk patents.”

All patents are junk patents. No patents are. What’s to distinguish? Oh yeah, the standards of obviousness and novelty. Great!

“I have never personally seen such an organization, and you are the first attorney who (probably because of your disillusionment) has admitted for working for such a organization.”

Admitted, exactly.

“Indeed, Stephan, the thought that you participated in such activities just astounds me. Why not find a company or firm that uses patents the way they were intended?”

They are intended to be used to sue competitors, are they not? Wow, how wonderful.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 05:27 PM by Stephan Kinsella]

MLS writes:”NOYB,[insult deleted]. Easy to do given the format of how comments are posted here.”

No. None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

Lonnie writes:

“Stephan:

How interesting, regarding your prosecution of hundreds of patent applications. As a matter of fact, so have I. Indeed, depending on how long after you became registered that you started prosecuting patents, you and I may have started prosecution at approximately the same time.”

Let the above, together with the fact that Stephan is a patent attorney, constitute Exhibit A.

“[insult]:

Let me see. [calls me a liar repeatedly].”

No, you’re the liar.

None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

I refer interested readers to Exhibit A, in which Lonnie himself implies the reverse of the premise of his insult here.

“Do not bother to quit your day job and do standout.”

To which Stephan replied:

“I think you mean standup.”

Anyone else find Lonnie reminding them more and more of Biff Tannen?

[Comment at 01/10/2010 05:56 PM by None Of Your Beeswax]

SK,No diatribe here, but merely a comment.I guess I must be “old school” because I do not recall ever having filed or had filed an application without first conducting a Pre-X search. The only exception has been a very few limited cases involving technology where the inventor was, in fact, the “prior art”, i.e., the technology was quite sophisticated (e.g., massive parallel processing) and the only references ever applied were those by the inventor himself. This is indeed a rare occurrence, but it does arise from time to time.

When I became corporate counsel and my duties required that I have work performed by outside counsel, Pre-X searches were mandatory, the person performing the search had to work in close conjunction with the person who would actually prepare the application, if any, senior examiners within the appropriate art units were consulted before the searches were even started so that guidance could be received, the results of the Pre-X searches had to be reviewed and reported back with a detailed analysis by the person who would prepare the application, and then I would independently review the results and present them to cognizant corporate management to determine if that an application was still deemed appropriate and consistent with current and future business plans…placing overriding emphasis on the corporation’s product and service offerings.

I readily admit that my approach is much more comprehensive than most, but as previously noted I believe the filing of an application is not a matter that should be taken lightly. Of course, some may say “But you are filing far fewer applications” than would otherwise be the case. My response is merely that there are many avenues at hand besides patents, and that I have no desire to move down an avenue where the cost in no way justifies the benefit conferred. That would be an unjustified waste of limited time and resources.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 06:22 PM by MLS]

MLS:Forget it. Stephan lives in some sort of parallel universe different from ours. I know the number of searches I have done myself is in the hundreds, at least. I have also reviewed thousands of patents, so many that I would be hard pressed to make even a vague estimate. So, while Stephan may “doubt it,” his standards of conduct as a patent attorney are different than what I was taught as a patent agent. But, hey, I guess he is still going to work and can still live with himself. He does not believe in IP, so going to work must be mentally painful. How does someone do a good job when they do not believe in what they are doing? Of course, he also believes in filing junk patents without doing a search. Weird. Is there something about being Libertarian that causes one to have skewed ethics and morals?Earwax:

You are a joke. Keep it up. I get a laugh out of every one of your posts.

Stephan:

Yes, I meant standup. Hard to catch all the typos.

As for your comment about the way patents were meant to be used, no, you are wrong. They were meant to communicate to the world an invention and the recognition that the right to make, use, sell or offer to sell the invention was given to that inventor for disclosing the invention to the world. However, some people, apparently those in the companies you have worked, have twisted this to be a weapon of ambush. Fortunately, the laws are changing so that such ambushes are harder and harder. Also fortunately, statistically less than 1% of all patents are treated in this way, and far less than 1% of all patent holders act in this way. I would also remind you, Stephan, than there is no such thing as an evil system, only evil people and evil actions.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:11 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Lonnie writes:”[insult deleted]:You are [insult deleted]. [insults deleted].”

No. None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:31 PM by None Of Your Beeswax]

Well, ain’t this a cute little troll-fest?He does not believe in IP, so going to work must be mentally painful.That’s silly. Suggesting that there’s something wrong with being an anti-patent patent attorney is like suggesting that there’s something wrong with being an anti-cancer oncologist.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:34 PM by Suzzle]

Suzzle:Actually, it is more akin to being a priest while being a devout Satanist. The conflict must be tremendous. I am curious as to how one does something well that one does not believe in, or believes is morally wrong? I would think Stephan would give up being a patent attorney and just be a plain attorney, or perhaps an engineer, if he can, of course.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:43 PM by Anonymous]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:45 PM by Anonymous]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:45 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:46 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Our resident troll writes:”[insult deleted]:I said I think you [insult deleted]. How can that be a nasty thing about you?”

How can it not?

“How can that not be true?”

Easily. None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

“After all, I am laughing at your post right now. lolol.”

That’s because you’re an asshole. In particular, it says more about you than it does about me.

“you are like a [insult deleted]”

No. None of the nasty things that you have said or implied about me are at all true.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:54 PM by None Of Your Beeswax]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:55 PM by Suzzle]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 07:56 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

[Comment at 01/10/2010 08:16 PM by Lonnie E. Holder]

MLS:”I guess I must be “old school” because I do not recall ever having filed or had filed an application without first conducting a Pre-X search.”Do you mean you paid an outside searcher, or just your own informal Internet search (which didn’t exist “old school”–did you go down to a local PTO shoebox repository and manually do searches pre-1995?).

It is extremely common for patents to be filed with no search at all. That said, I do searches myself–not a formal one, but the informal PTO type search. But it’s often not done.

“I readily admit that my approach is much more comprehensive than most, but as previously noted I believe the filing of an application is not a matter that should be taken lightly.”

The patent system permits and is rife with junk patent filings. That you didn’t do it doesn’t change this.

Lonnie: “Forget it. Stephan lives in some sort of parallel universe different from ours. I know the number of searches I have done myself is in the hundreds, at least.”

Me, too, probably. So what? How does this prove that the patent system is legitimate? How does this militate against the observation that thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?

“He does not believe in IP, so going to work must be mentally painful. How does someone do a good job when they do not believe in what they are doing?”

This is nonsense. More of the “we will penalize you if you don’t toe the line.” See my postsPatent Lawyers Who Don’t Toe the Line Should Be Punished!; An Anti-Patent PatentAttorney? Oh my Gawd!; Is It So Crazy For A Patent Attorney To Think Patents Harm Innovation?.

It is necessary for my own company to obtain patents for defensive purposes, given the evil monopolistic, protectionist, mercantalist system foisted on us by pro-patent types. Given the system we are in, it is good that my client obtain patents, just as it’s good that a tax victim have a good tax attorney. In a free society neither patent lawyers nor tax attorneys would exist.

“Of course, he also believes in filing junk patents without doing a search. Weird.”

It’s not that I “believe in it”, it’s that I believe that it is commonly done. I don’t believe in taxes either, but I believe they exist. Notice that MLS above did not deny that this is done.

“As for your comment about the way patents were meant to be used, no, you are wrong. They were meant to communicate to the world an invention and the recognition that the right to make, use, sell or offer to sell the invention was given to that inventor for disclosing the invention to the world.”

How do you know what they “were” “meant” to do? We know that the statute gives the patentee a right to extort and sue. And it’s predictable that if you dish out this right, people will take and use it. Surprise, Marshall Texas is prospering!

“However, some people, apparently those in the companies you have worked, have twisted this to be a weapon of ambush.”

SHOCKING!!

“Fortunately, the laws are changing so that such ambushes are harder and harder.”

Nonsense. The law is not changing fundamentally. See my Radical Patent Reform Is Not on the Way. Patent shills squeal like scalded dogs when they sense any potential dilution of patent “strength.”

“Also fortunately, statistically less than 1% of all patents are treated in this way, and far less than 1% of all patent holders act in this way. I would also remind you, Stephan, than there is no such thing as an evil system, only evil people and evil actions.”

It is evil for the state to hand out legal monopolies to people, that they can use to extort, sue, ruin in the state’s illegitimate courts.

Lonnie: “Actually, it is more akin to being a priest while being a devout Satanist. The conflict must be tremendous. I am curious as to how one does something well that one does not believe in, or believes is morally wrong? I would think Stephan would give up being a patent attorney and just be a plain attorney, or perhaps an engineer, if he can, of course.”

My career is none of your business and is irrelevant to my case that IP is illegitimate. Of course patent shills would love for any patent attorney to toe the line and for those who don’t to leave the profession so that they can tar and feather any opponents as being ignorant of the workings of the system they oppose. Too bad, podnah.

[Comment at 01/10/2010 09:05 PM by Stephan Kinsella]

Stephan:”Do you mean you paid an outside searcher, or just your own informal Internet search (which didn’t exist “old school”–did you go down to a local PTO shoebox repository and manually do searches pre-1995?).”Why would you need to do manual searches for art pre-1995? The USPTO can search patents to 1976. Patent Surf and Google Patents permit pretty darn good searching for much longer than that, I believe back to the beginning. Then there are other software packages that have wonderful search algorithms, such as Goldfire. These searches are not any more “informal” than the searches conducted by the dozens of search firms that exist. That brings up a separate point as to why so many search firms exist if no one is doing any searching, but no need to dilute the conversation further.

“Me, too, probably. So what? How does this prove that the patent system is legitimate? How does this militate against the observation that thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?”

Conversely, how does this prove the patent system is illegitimate? It does not. How does this prove that “thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?” It does not. While there MAY be thousands of junk patents filed (which may be true), and some may be allowed, you have not provided evidence that those thousands of junk patents outweigh the benefits of the patent system.

“It is necessary for my own company to obtain patents for defensive purposes, given the evil monopolistic, protectionist, mercantalist system foisted on us by pro-patent types.”

This sentence is not even an argument, but a pejorative, jingoistic diatribe without meaning or relevance to the topic at hand.

“How do you know what they “were” “meant” to do? We know that the statute gives the patentee a right to extort and sue.”

So, in your vernacular guns give people the right to murder, threaten, and maim. Knives are for cutting, extortion and tortue. Cars are for running people down. Patents do not give a patentee a right to do anything other than prevent others from making, using, selling or offering for sale their invention. That is the only right it gives a patentee. However, it also protects a patentee that goes to a company with an invention when the company takes that invention for their own without any compensation for the inventor who brought it to them, which happens far too often even with patent protection. So, the patent system does give a patentee an opportunity to receive compensation for his invention, especially when the invention was stolen without permission. A patent also permits a company to spend tens of millions or hundreds of millions to develop an invention and then have an opportunity to get a return on that investment rather than having some company without the ability to be as creative steal the invention.

“Nonsense. The law is not changing fundamentally.”

I see. So the elimination of submarine patents was not a fundamental change. I guess Bilski was not a fundamental change. I guess KSR was not a fundamental change. How many would you like? The laws have been changing to be less favorable to patentees for a while. I am perfectly fine with the changes. I think, given that patentees rarely win in court (only about 20% of the time), that patent laws needed changed to be more restrictive, and we have seen that trend over the last half decade.

As for patent shills screaming like scalded dogs, Libertarians scream like little girls every time someone points out that the system is abused far less often than they like to make out, and then roll out their religious dogma rather than using facts.

“It is evil for the state to hand out legal monopolies to people, that they can use to extort, sue, ruin in the state’s illegitimate courts.”

Religious dogma. It is evil for people to steal other’s identities. It is evil for people to take the inventions of others. It is evil for people to run red lights. Evil is everywhere, if you just point it out. Of course, there are two kinds of evil, the kind that creates actual harm (and I remind you that NO ONE has ever pointed out that the balance of patents is harmful, and several researchers with ACTUAL MATH have shown that patents are beneficial), and the imagined kind.

“My career is none of your business and is irrelevant to my case that IP is illegitimate.”

I was not talking to you. I can talk about you and your career to MLS all I like and if you do not like it, too bad, podnah.

I remained stunned at an attorney who does not believe in the legitimacy of his job.

[Comment at 01/11/2010 05:43 AM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Suzzle:You will note that I also pointed out that the posts were mine.

[Comment at 01/11/2010 05:45 AM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Lonnie:”Why would you need to do manual searches for art pre-1995?”I meant if you were practicing before 1995, how would you do it? Etc.

“Conversely, how does this prove the patent system is illegitimate? It does not.”

It doesn’t. Non-practitioners have an unrealistic, romanticized notion of how the system operates and is used.

“How does this prove that “thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?” It does not. While there MAY be thousands of junk patents filed (which may be true), and some may be allowed, you have not provided evidence that those thousands of junk patents outweigh the benefits of the patent system.”

The burden is on you to show that the system as a whole is indeed worth it.

“So, in your vernacular guns give people the right to murder, threaten, and maim. Knives are for cutting, extortion and tortue. Cars are for running people down. Patents do not give a patentee a right to do anything other than prevent others from making, using, selling or offering for sale their invention.”

This is disingenuous. Guns are for shooting and killing people. That may be used for good or evil–for offense, or defense.

Patents are for suing people if they don’t pay protection money. That right should not exist at all.

“A patent also permits a company to spend tens of millions or hundreds of millions to develop an invention and then have an opportunity to get a return on that investment rather than having some company without the ability to be as creative steal the invention.”

You are giving one of hte pro-patent arguments for *why* patent rights should be granted. But this does not change the nature of a patent right–it is a monopoly grant, a right to sue.

“As for patent shills screaming like scalded dogs, Libertarians scream like little girls every time someone points out that the system is abused far less often than they like to make out, and then roll out their religious dogma rather than using facts.”

The problem is not that the system is abused. The problem is it is inherently immoral, by its nature. It cannot help but be abused.

“I remained stunned at an attorney who does not believe in the legitimacy of his job.”

who cares what you are stunned by? This does not gainsay that patents are immoral.

[Comment at 01/11/2010 06:07 AM by Stephan Kinsella]

Our resident troll writes:”Patentees rarely win in court (only about 20% of the time).”A disingenuous factoid.

That’s because losing a patent suit is so damn expensive that most of the other 80% of cases get settled out of court. The ones that don’t are precisely the ones where the defendant feels he has a quite strong case.

Tell me, what percentage of patent suits go to a judgment that the defendant wins?

“I remind you that NO ONE has ever pointed out that the balance of patents is harmful, and several researchers with ACTUAL MATH have shown that patents are beneficial.”

Several industry-paid “researchers” perhaps. Independent researchers have found the opposite, as has been noted at this site several times.

Besides, as others have pointed out, the burden of proof is on those seeking to curtail liberty to prove that it’s beneficial, rather than on those seeking to keep or restore liberty to prove that the curtailment is not.

[Comment at 01/11/2010 06:48 AM by None Of Your Beeswax]

Earwax writes:”That’s because losing a patent suit is so damn expensive that most of the other 80% of cases get settled out of court. The ones that don’t are precisely the ones where the defendant feels he has a quite strong case.”That is not true at all. Indeed, most of the other ones are either dismissed, lost or other situations that benefit the plaintiff.

“Tell me, what percentage of patent suits go to a judgment that the defendant wins?”

Once you get as far as the trial, last I saw about 70 or 80% of those cases are won by the plaintiff – hence the 20%.

“Several industry-paid “researchers” perhaps. Independent researchers have found the opposite, as has been noted at this site several times.”

I have provided several papers by independent university researchers showing that patents provide benefits to society. Every time I provide those papers they are ignored. It is always easier to ignore facts that disagree with dogma versus providing superior facts.

“Besides, as others have pointed out, the burden of proof is on those seeking to curtail liberty to prove that it’s beneficial…”

Already been done…multiple times.

[Comment at 01/11/2010 06:56 AM by Lonnie E. Holder]

Stephan:Why would you need to do manual searches for art pre-1995?I meant if you were practicing before 1995, how would you do it? Etc.

I understand your point. Yes, if you were practicing before 1995 searches were much more of a pain. Indeed, I probably would have recommended against searches at that time as being time consuming and expensive. How wonderful that we live in the era we do where searches are relatively quick and cheap.

“How does this prove that “thousands of junk patents are filed (and allowed)?” It does not. While there MAY be thousands of junk patents filed (which may be true), and some may be allowed, you have not provided evidence that those thousands of junk patents outweigh the benefits of the patent system.”

The burden is on you to show that the system as a whole is indeed worth it.

I have provided numerous papers and studies that show the benefit of the patent system. I note that each time I post those references that they are conveniently ignored, or some excuse is given as to why they are somehow irrelevant (many of them belief related). Oh well.

“So, in your vernacular guns give people the right to murder, threaten, and maim. Knives are for cutting, extortion and tortue. Cars are for running people down. Patents do not give a patentee a right to do anything other than prevent others from making, using, selling or offering for sale their invention.”

This is disingenuous. Guns are for shooting and killing people. That may be used for good or evil–for offense, or defense.

Patents are for suing people if they don’t pay protection money. That right should not exist at all.

Illogical. If patents are “for suing people if they don’t pay protection money,” then why are 98.5% of all patents never involved in a conflict? Answer: because that is NOT the purpose of the patent system.

I should also point out that guns are NOT for shooting and killing people. Guns are for expelling a projectile at high velocity. That function is neither moral or immoral. When the projectile is used to acquire food, then I argue that the function is moral. When the projectile is used to ward off those who would harm my family or take my property, its function is moral. When the projectile is used to kill without provocation or for threatening someone to take that which legally belongs to them, it is immoral.

A patent also permits a company to spend tens of millions or hundreds of millions to develop an invention and then have an opportunity to get a return on that investment rather than having some company without the ability to be as creative steal the invention.”

You are giving one of hte pro-patent arguments for *why* patent rights should be granted. But this does not change the nature of a patent right–it is a monopoly grant, a right to sue.

*Sigh* You have a one-track mind. Very few patents are ever involved in a suit. If the only purpose of a patent is right to sue, then the overwhelming number of companies are doing it wrong.

“As for patent shills screaming like scalded dogs, Libertarians scream like little girls every time someone points out that the system is abused far less often than they like to make out, and then roll out their religious dogma rather than using facts.”

The problem is not that the system is abused. The problem is it is inherently immoral, by its nature. It cannot help but be abused.

This statement is one of belief or religion and not one of fact. All systems, whether home-owner associations or Libertarianism, have the capability of being abused. The existence of a system lends itself to being abused, if the intent of the person involved with the system is abuse. Of course, lack of systems also generate abuses as well. Darned if you do, darned if you don’t. The question is whether we are better off with systems rather than without. I believe we are better off with systems – though less onerous (SOX) and less complicated (taxes) systems than we have right now.

I remained stunned at an attorney who does not believe in the legitimacy of his job.

who cares what you are stunned by? This does not gainsay that patents are immoral.