From the Mises blog; archived comments below. See also KOL190 | On Life without Patents and Copyright: Or, But Who Would Pick the Cotton? (PFS 2015)

Two Types of Abolitionism: IP and Chattel Slavery

|

|

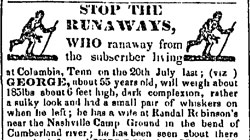

| Assisting in the liberation of human property was a Federal crime. | Unauthorized sharing of “Intellectual Property” is a Federal crime. |

“Redefining Property: Lessons from American History” is a great article on QuestionCopyright.org showing striking similarities in the arguments made by both advocates of slavery, and of IP, against slavery and IP abolitionists, respectively. For example, advocates of both slavery and IP argued (a) that it’s blessed by the Constitution; (b) that these are “property rights,” being violated by the underground railroad/piracy; (c) punishment for both “crimes” (helping runaway slaves, pirating IP) became increasingly severe; (d) and both types of abolitionists were called extremists (and the related view that any “reform” should be moderate and gradual instead of principled, radical, and instant); and other similarities. And as the article points out, there are other similarities: namely, that slavery enslaves people, while IP enslaves thinkers.

As the article notes,

I hear this a lot:

“IP is problematic, but the decision to free works should be the artist’s choice.” [3]

Legally artists DO have the right to choose whether to release works freely or place copyright restrictions on them.1 So we don’t need to discuss “should.” The nice response is to say, “yes they have that choice, and therefore I wish to present arguments in favor of choosing freedom.” Which I do.

But I can’t help imagining this argument in the early 1800’s:

“Slavery is problematic, but the decision to free slaves should be the slaveholder’s choice.”

As long as the discussion is about “owner’s choice,” we don’t have to question how we define property.

|

|

| Jack Valenti: “We are facing a very new and a very troubling assault on our fiscal security, on our very economic life and we are facing it from a thing called the video cassette recorder and its necessary companion called the blank tape.” [1] | E. N. Elliott: “(W)itness…the existence of the ‘underground railroad,’ and of a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property….” [2] |

(h/t Rob Wicks)

Update: See also KOL190 | On Life without Patents and Copyright: Or, But Who Would Pick the Cotton? (PFS 2015)

February 15, 2011 at 9:10 am

-

Why… to demand the abolition of the private owning slaves would be communist! /sarcasm

February 15, 2011 at 9:19 am

-

La fuite en avant for Stephan Kinsella. Just after being exposed for his shameless defamation of true economists, he continues with more of his fallacious defamation.

February 15, 2011 at 9:57 am

-

What has been exposed is that you run away from debates.

February 15, 2011 at 10:04 am

-

You have a very low standard for the term “defamation”. Disagreement is not defamation.

February 15, 2011 at 6:24 pm

-

Accusing IP creators of enslaving people is defamation.

February 15, 2011 at 7:49 pm

-

So what if it is?

February 16, 2011 at 12:26 am

-

… or, more accurately, it would be.

Breaking out the strawmen early on this one, eh?

February 15, 2011 at 10:03 am

-

I’m sorry, but comparing the abolition of slavery with the abolition of copyright is bordering on offensive. Treating a human as property is not the same as treating an idea as property.

Whatever your arguments might be for removal of IP; this is not a good one.

What next? Hitler believed in copyrights therefore they’re bad?

February 15, 2011 at 10:08 am

-

“What next? Hitler believed in copyrights therefore they’re bad?”

Wow. So much for thinking detailed thoughts on detailed topics, huh?

I found the analogy between human slavery and IP very interesting, especially because both people were claiming “their” way of life was being threatened. What about that is taboo?

I don’t understand why there are certain topics which some (obviously, you) think are so sacred as to be beyond commentary or analogy. Human slavery was a tyrannical tragedy of epic proportions. To decide it is not useful for lessons in other areas doesn’t enhance our chances of repeating such tyranny; it limits it.

February 15, 2011 at 10:24 am

-

That last sentence should have said:

“To decide it is not useful for lessons in other areas doesn’t limit our chances of repeating such tyranny; it enhances it.”

February 15, 2011 at 10:47 am

February 15, 2011 at 10:44 am

February 15, 2011 at 3:37 pm

-

Exactly, Onus.

Ironically, I have argued that opposing all forms of IP rights is tantamount to supporting a form of slavery, as both hold that production for external economies is acceptable. Of course no one would choose to be a slave voluntarily, and so would naturally prefer to spend their time doing something else; i.e. produce for internal economies.

Slaves would free themselves if they could, and eventually they were. Since property rights are a human device, it is possible to hold property to be something, and later abolish it.

No one is saying that IP could not be abolished. The question is whether that is preferable.

February 15, 2011 at 3:58 pm

-

“and so would naturally prefer to spend their time doing something else; i.e. produce for internal economies”

You’ve stretched this phrase so far beyond its original meaning that you’ve lost sight of what you are actually saying. Here’s the reality of what you are pretending to describe —

There are business practices that are currently built around the Imaginary Property regime imposed by our all-knowing Ministry of Love. These practices would probably have to change, should this monopoly-protectionism to come to an ignominious end. In the absence of IP, there are certain business models that, being wholly dependent on IP protectionism, would no longer be viable.

Cry me a river.

February 15, 2011 at 4:24 pm

-

Phinn,

There are life forms that are currently built around the imaginary property regime that air is in the public domain. The practices associated with breathing would probably have to change, should the protectionism of the public domain of air come to an ignominious end. In the absence of air, there are certain life forms that, being wholly dependent on breathing, will no longer be viable.

Cry me a river. Especially if you are one of the affected life forms.

February 15, 2011 at 4:50 pm

-

You just violated my “property” rights in the words I used. Pay up, buddy, or you’ll soon get to know the “human device” known as SWAT teams and jail cells. $10,000 ought to do it. For now.

February 15, 2011 at 6:24 pm

-

You would have to prove it was a derivative work, but I would defend as a parady, and I would win. Sorry, no SWAT for you!

February 15, 2011 at 6:49 pm

-

There are life forms that are currently built around the imaginary property regime that air is in the public domain. The practices associated with breathing would probably have to change, should the protectionism of the public domain of air come to an ignominious end. In the absence of air, there are certain life forms that, being wholly dependent on breathing, will no longer be viable.

Air isn’t scarce, and doesn’t require any artificial efforts to keep it that way. The default state is plentiful, even in the middle of nowhere.

February 15, 2011 at 8:16 pm

-

“You would have to prove it was a derivative work”

Yes, and a “derivative work” is defined as whatever it needs to mean in order to exclude examples that IP advocates agree would be ridiculous.

February 15, 2011 at 6:53 pm

-

comparing the abolition of slavery with the abolition of copyright is bordering on offensive. Treating a human as property is not the same as treating an idea as property.

I don’t think it’s equating slavery with IP, rather the arguments of their respective proponents, and the way business models based on them are resistant to change.

February 15, 2011 at 10:44 am

-

I’m sorry, but comparing the abolition of slavery with the abolition of copyright is bordering on offensive.

The analogy is a good one. If the regime decides that you have violated copyright and if you ignore or resist their attempts to confiscate your property (in vastly greater proportion to the supposed cost of the crime), they will treat you exactly the same as a fugitive slave. They will track you down anywhere in the USA, arrest you at gunpoint, shooting you if you resist, put you in a cage and if you are insufficiently cooperative they will shackle you and torture you with solitary confinement. It may become even worse than slavery, if the copyright treaties permit the extradition or international prosecution of suspected violators. In the 1800s even slaves were not molested if they made it to Canada.

Treating a human as property is not the same as treating an idea as property.

They are treating your thoughts (intellect) as their property, which amounts to slavery. And as stated above, they will physically imprison and confiscate the property of anyone whom they deem to have violated their thought crimes. If that isn’t slavery then what is? Is it only slavery if you’re forced to pick cotton?

Not only the for-profit purveyors of copied materials are threatened but even the poorest students and grandmothers who may be tracked down using their internet addresses are threatened with severe fines (to the tune of hundreds of dollars for “stealing” each song worth no more than one dollar). And of course any of these poor people who decline to be fined will be hauled away to prison and shot dead if they resist. In fact the poorer one is, the more likely to be robbed, enslaved or killed in the name of copyright law, because they lack both the knowledge to evade detection and the financial resources to defend themselves.

What next? Hitler believed in copyrights therefore they’re bad?

Hitler is also a very apt analogy for copyright law. The Nazis never hesitated to physically attack any individual or group who declined to cooperate the “greater good” as their government defined it. The imposition of copyright law is no more moral than anything that Hitler did, merely because the government which enforces the law was elected by popular vote.

If you want to consider copyright law as an issue to be determined by popular consent, then consider the fact that the vast majority of citizens commit offenses under the copyright laws nearly every day (when recording TV shows, photocopying recipes, copying music from CDs onto their MP3 players). Obviously they do not support copyright law. Is the imposition by government of a law which the people clearly do not support, backed by brutal fines, imprisonment and even torture and death, less tyrannical than anything that Hitler did?

February 15, 2011 at 12:27 pm

-

A closer kin to human slavery is human taxation, which in perhaps its earliest manifestation was known as tribute–the requirement of regular payments of compensation by conquered people to their conquerors. Thus taxation was devised as an alternative to killing or enslaving conquered people because it was more productive of the fruits of those other people’s labor. Of course IP could not exist in the absence of the state and its enslaving taxation, so your analogy is all the more compelling for that reason.

February 15, 2011 at 6:15 pm

-

Interesting. I did not know this history. I learn something new every day. Thanks.

February 15, 2011 at 6:36 pm

-

That is incorrect, taxation is the result of a king monopolizing justice, and hence being able to unilaterally determine what he is to be paid for this justice.

A conquering tribe may be able to steal from the conquered, but it does not follow that a tribal lord can tax his fellow tribesmen.

February 15, 2011 at 8:21 pm

-

“That is incorrect, taxation is the result of a king monopolizing justice, and hence being able to unilaterally determine what he is to be paid for this justice.”

You skipped the very important step of the king being able to compel people to pay for justice at all, which is what taxation is. In other words, the king conquered subjects and offered them an alternative to death or slavery.

“A conquering tribe may be able to steal from the conquered, but it does not follow that a tribal lord can tax his fellow tribesmen.”

Where does this categorical difference come from? Just like with the “citizenry”, if enough of the tribesmen believe that the tribal lord is owed by all the tribesmen, then a dissenting tribesman would suffer the same fate as a tax evading citizen.

February 15, 2011 at 12:28 pm

-

You hoo (to those criticizing Kinsella) We all already know that copyright is not the same as slavery. It’s the poor justifications and reasoning they use that’s the same, get it. But even if it was a comparison, it’s a fair one. Copyright has shown itself to be a perfect example of the slippery slope argument. But even if it wasn’t, there are still plenty of examples of where IP is hideously evil. ie. Like how pharmaceutical companies sued African nations in the world court to block the import of generic AIDS drugs from India. Like the role patents played in banning DDT, which by some estimates has caused 50 million malaria deaths. Maybe not copyrights, but comparing patents to crimes against humanity is totally fair on any level.

Even if you believe that something like copyright is free market. This is a perfect example demonstrating that mainstream reasoning on the matter is outright stupid.

February 15, 2011 at 12:54 pm

-

@Onus. There is nothing offensive about how Nina Paley presented the argument. Forcible government always bears some resemblance to slavery. Indeed, it might well be argued that chattel slavery is simply an extremely abusive form of government, and each plantation was essentially a tiny patch of despotism within the borders of the USA. I myself have compared any number of statist outrages to various aspects of slavery. Being a black man from the south with a strong family background and a fair amount of knowledge about both slavery and its aftermath, I usually don’t get much grief about it, but the perception would naturally be different if a white person did what I do. That’s why, I imagine, Paley mentioned both the similarities and the differences.

February 15, 2011 at 3:50 pm

-

Another black Libertarian who uses Linux? High-five!

February 15, 2011 at 4:13 pm

-

Robert,

With all due respect to a black man from the south, you are pretty confused about the issues here.

All property carries enforcement privileges against others who violate those privileges. The outrages you have against slavery are not a function of government support for it, it is a function of the vesting of property rights in other humans. Like all logical fallacies, if the premise is wrong the conclusion is wrong.

The premise was that humans can be the property of other humans. Once that premise is accepted, all the other “outrages” are simply an enforcement of those property rights. The means of that enforcement is irrelevant to the central legitimacy of the premise.

It is wrong to define humans as property, not because such property rights are enforceable, but because to do so violates a higher principle, that all [humans] are created equal, and have equal rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. This conflict was resolved at the time by refusing to recognize African slaves as human. Obviously that was wrong, and explains why we now generally believe the premise of humans as property cannot stand.

The fact that ridiculous arguments were made at the time by today’s standards, is completely irrelevant to the IP argument unless it can be shown that particular arguments being made about slavery are analogous to arguments in the IP debate.

The analogy for IP opponents is that just like slavery, the premise concerning what can be property is wrong; IP as property cannot stand. Why? Is IP the bondage of human being by other human beings? To be against the concept of slaves as property is in no way analogous to “original works” as property. One premise certainly does not prove the other, and whether one or the other or both are enforced by government is completely irrelevant to the issue, unless of course what you are really saying is that all government existence is a “statist outrage”. You wouldn’t be the first. SK has said, “We have IP becasuse we have the state”.

The concept that IP carries property rights is a long way from dead, despite SK’s declaration of victory. Last I looked one can still enforce rights in IP.

February 15, 2011 at 4:28 pm

-

My offer stands – put IP in a basket and show it to me. Don’t show me paper, ink, binding, glue, or leather. Don’t show me a CD. Don’t show me a DVD. Don’t play vibrations of air molecules. Show me an indisputable material called IP, in it’s physical manifestation, that cannot be confused with the materials it’s presented on or the means in which it’s transmitted. Demonstrate to me how it can be taken from someone else so they can no longer use it. Demonstrate to me how it can be damaged in such a way that it cannot be used in its intended purpose. Show me what IP looks like and you’ll have a rational argument. Until then, don’t belittle people.

Just count yourself lucky that you can’t, because if you can, I’ll homestead it and shut down your ability to speak, live, or even move without paying me hefty royalties.

February 15, 2011 at 7:23 pm

-

Wildberry,

Without government support for slavery, it is simple crime. With government enforcement for IP, it is simple crime. It would be criminal for someone to kidnap me and force me to pick cotton, unless we are using state definitions of crime, correct? Would it not be similarly criminal to take a person’s computer simply because he has information on it and did not pay someone to be able have a copy of it? Also, just as you rightly say that slavery violates the higher principle that all humans are created equal, does intellectual property not violate the higher principle that human beings have the right to configure their justly-acquired property in any configuration they find pleasing?

Certainly, IP is not as oppressive as slavery, and Paley did not attempt to claim that it is. However, forcing a man to avoid using the contents of his own mind (such as with a song he has heard, or a formula he has either learned or developed himself) to perform certain tasks with his own property is still a type of oppression. Things can be similar without evoking the same emotions. I would not claim that slavery and IP evoke the same emotions. A star and a marble do not conjure the same sense of wonder within many people, yet they both have gravitational fields. Making an analogy between them does not diminish the star nor does it magnify the marble.

February 15, 2011 at 10:30 pm

-

@Robert Wicks February 15, 2011 at 7:23 pm

“It would be criminal for someone to kidnap me and force me to pick cotton, unless we are using state definitions of crime, correct?”

Not sure what you mean here. What you describe is kidnapping by most any definition.

Slavery is state sanctioned kidnapping, meaning the kidnapped slave does not have a cause of action against the kidnapper.

“Would it not be similarly criminal to take a person’s computer simply because he has information on it and did not pay someone to be able have a copy of it?”

It would be a criminal act to take someone’s computer for nearly any reason. If the computer is used to commit another crime or civil offense, that act would be punished or damages would be imposed.

So the question is whether it is an offense to copy someone else’s work. I gather you think not.

“does intellectual property not violate the higher principle that human beings have the right to configure their justly-acquired property in any configuration they find pleasing?”

Not really. Just because you “justly-acquire” some property does not entitle you to do with it as you please without limits. Those limits exist at the margins of the rights of others. So you are back to where we started; Is using your property in a particular way a violation of another’s rights? If so, there is a legitimate basis to limit your rights to that particular use.

“However, forcing a man to avoid using the contents of his own mind (such as with a song he has heard, or a formula he has either learned or developed himself) to perform certain tasks with his own property is still a type of oppression.”

First, if IP laws operated as you say, I would agree that it is wrong. I hope you are not bothered by the fact that they do not. There is no restriction in IP laws on the use of one’s mind, or in recalling a song he has heard, even singing it to himself or his friends and family. Formulas are explicitly excluded from an form of IP protection, except perhaps for some esoteric applications in the context of software/hardware technologies.

“Making an analogy between them does not diminish the star nor does it magnify the marble.”

I like analogies. They are a valuable tool in gaining understanding. They can help distinguish things by pointing to similarities and differences between them. Some people object to them because they are “vague”. Vagueness causes me no real problem, because you can always polish the meaning of things you say to other people and what they say to you and reduce the vagueness. I find it a shallow objection that is used to attempt to derail a discussion about a difficult topic. If there is vagueness about a thing, talking it over often helps. What’s wrong with that? Anyway, I think the analogy here fails.

The analogy being offered here is that slavery was rationalized in ways that appear patently false today. By implication, justification for IP is equally patently false, and if you don’t think so, you should think of yourself as the type of person who once supported slavery. Throw in the hated State for good measure, and anyone who believes in IP rights should feel ashamed.

Sorry, that dog don’t hunt with me.

February 15, 2011 at 11:03 pm

-

There is no restriction in IP laws on the use of one’s mind, or in recalling a song he has heard, even singing it to himself or his friends and family

Yeah, the legislation merely dictates that you can’t get paid for it! You own your body (for now), which includes your voice, and the neurons that encode the pattern of notes, but if you try to trade an act of your OWN BODY for something, given willingly by someone who owns that thing, on a voluntary, mutually-agreed basis, the State will swarm in on you like locusts.

Which amply shows what Imaginary Property legislation is ACTUALLY concerned with — like all statist monopoly privileges, it’s all about protecting market share.

February 15, 2011 at 8:29 pm

-

“Like all logical fallacies, if the premise is wrong the conclusion is wrong.”

That is not a logical fallacy. There are valid arguments with wrong premises and right conclusions.

What you are suggesting here is that if something is ever argued poorly or starting from false premises, whatever the conclusion is it must be false. As a dramatic example of the error here, consider the (obviously) false premise of “A and not A” (a contradiction). Every proposition imaginable follows as a valid conclusion from this premise and so that would lead you to conclude that every proposition is false, because they are all conclusions of an argument that begins with false premises!

And maybe this explains what is going on here! From what I can tell, many of the IP advocates seem to think that if they find a potential hole in the anti-IP side (I don’t think they have but let’s assume they have) that is conclusive reasoning that IP is legitimate! Hence the complete non-existence of a property rights theory to incorporate IP, with only a (poor) attack on the property rights theory that excludes IP.

February 16, 2011 at 1:56 am

-

This conflict was resolved at the time by refusing to recognize African slaves as human.

What are you talking about? Do you mean the “slaves count for 3/5s” rule in the Constitution? You know that’s an anti-slavery measure, right? If the abolitionists had had their way, slaves wouldn’t have counted at all! Counting slaves for the purpose of apportioning votes gives more power to the slave owners — it’s not like the slaves got to cast those votes!

February 16, 2011 at 2:53 pm

-

I am simply saying that to resolve “All men are created…”, and not have that apply to slaves, it was necessary to consider slaves somthing other than “All men”, i.e. non-human.

That was a contradiction of principle which eventaully fell, as it had to.

February 15, 2011 at 4:38 pm

-

J. Murray,

Put your checking account in a basket and show it to me. Don’t show me paper, ink, binding, glue, or leather. Don’t show me a CD. Don’t show me a DVD. Don’t play vibrations of air molecules.

You don’t believe checking accounts exist?

February 15, 2011 at 4:58 pm

-

They do exist because I can demonstrate that your use of mine impedes my use of it because the cash is no longer on account. The money cannot be simultaneously used by two or more individuals (hence why I’m also an opponent of fractional reserve banking) without making the resources unusable by the originator. I can obtain physical representation of that account that fits the requirements – can be rendered unusable by the existing owner via theft or damage. The same cannot be said for IP.

Another way to say it is my bank account follows the Laws of Conservation. My account may be converted and changed, but it cannot be created out of thin air (it also cannot be truly destroyed, just altered in a way that is counter to my desired ends as the owner, rendering it unusable to me). IP can be created and replicated out of thin air, thus violating basic physical laws of the universe thus not being real property but imaginary.

Insert quarter, try again.

Or can you demonstrate to me that IP follows the same Laws of Conservation that matter, energy, motion, etc, do?

February 15, 2011 at 6:06 pm

-

J. Murray,

No one else can use it because it is your property. If everyone else could use it, you would not have exclusive economic interest in it. It is not because the particular numbers in a particular ledger are scarce, it is that they are made scarce by vesting property rights to your specific account number. That is just another way of saying that your checking account is your property, and you have exclusive rights to it. Also, you can’t counterfeit money by copying your own numbers into your account, or copying them into another account.

You are simply describing the way property works. It works that way because humans designed it to work that way. Therefore, property is a human device.

Even slaves can be called property if we decided to do it. Our common objection is why it doesn’t exist today. It violates our contemporary ethics because we hold that a superior principle of liberty trumps it.

Laws of conservation includes the conservation of energy. Energy is only tangible when it operates on physical matter. Anyway, no one is saying that IP is subject to these laws in any but the most metaphysical ways. Can you demonstrate that an idea follows these laws in the way you mean? Then why would say that original works, which are of the NATURE of ideas, should? We need only agree to treat something like property for it to be done. It is a human device.

Like many here, you are simply choosing to define property in such a way that it excludes certain phenomena, like original works of authorship. You do that in order to arrive at a desired outcome, much like a scientist who fudges the data to make it reach the “right” conclusion.

February 15, 2011 at 6:22 pm

-

I think your use of a checking account as property is a poor analogy.

Your property is the money that you have deposited into the bank. You own the money; a “checking account” is merely an abstract construct meant to denote that you have property on deposit at the bank.

For example, let’s take the following list of things currently in my living room: TV set, DVD player, couch, Roku, chair, copy of Human Action, and Tivo. Do I own “the list”? Or do I own each of those things on the list?

February 15, 2011 at 6:34 pm

-

The problem here is that the list of things that your checking account refers to is fiat money, hence it is a purely virtual good. Fiat money is a legal monopoly on a money supply.

If IP communism were valid, then the legal monopoly on printing fiat money would be abolished, and your checking account would instantly become worthless, having either the same amount of money or an unlimited amount (the result would be the same). The money market would be destroyed and no one would be any better off from it.

February 15, 2011 at 8:35 pm

-

“IP communism”

For the love of god please read Marx before you re-interpret his theory of property and present it as anti-Marxian.

“then the legal monopoly on printing fiat money would be abolished, and your checking account would instantly become worthless, having either the same amount of money or an unlimited amount (the result would be the same). The money market would be destroyed and no one would be any better off from it.”

Oh, wait, you think a monopoly on the money supply is a good thing!? I think it is deliciously ironic, in only that way a statist (perhaps one in denial) can provide, to say that “no one would be any better off” when they are actually not denied a choice in what to do!!

Yes, the advocates of monopoly (=government) will eventually admit that they in fact know what people want better than those people themselves do, and that’s why they should not have choices and rather there needs to be only one provider: the one deemed best by the dictator.

February 15, 2011 at 6:57 pm

-

GoldBacon,

Are you sure? Is your money actually “there”, physically? Or is it simply a promise by the bank to turn those numbers in your account into cash on demand.

It is the uniform promise to pay that gives value to your checking account and permits you to use it as a money substitute.

If you wrote this list on a piece of paper, along with “I hereby grant free and clear title to the things on this list to Wildberry” and signed it, what would that list have become?

You would have just created a security interest in your things. You have created property out of thin air. I can take that promise, which was intangible just before you wrote it on the paper, and exercise my new exclusive economic rights and sell it, give it away etc., without every actually seeing the goods you have conveyed. I have no idea if they exist. My only evidence is this contract.

You can do this because you owned the physical items, but you created a property interest in them by fixing an intangible promise on a piece of paper. Property of all kinds are a human device. Property may be an actual thing, or a security interest in a thing. One is a tangible, physical thing, and the other is an intangible promise. The paper is not the promise. It is the promise that is enforceable. The paper is simply EVIDENCE of the promise.

A story that I author is intangible, because it comes out of my head, using things (knowledge, experience, words, ideas, time/space relationships, descriptions of characters, dialogue, etc.) that I specifically choose to express. The evidence of that intangible work is the FIXATION upon a tangible medium. It is not the paper that is the property, but the story.

February 15, 2011 at 9:07 pm

-

Can you define property for me? An intangible promise is property?

If I copy a pdf online what exactly am I stealing? If it is a monetary reward, is it stealing when I lend my books or give them away to my friends?

February 15, 2011 at 9:39 pm

-

>>Are you sure? Is your money actually “there”, physically? Or is it simply a promise by the bank to turn those numbers in your account into cash on demand.

Remarkably, you are hitting on a very important topic within Austrian Economics. The debate between full demand-on-deposit vs. fractional reserve banking is pretty fascinating.

If you have time, definitely check out Jesus Huerta de Soto’s brilliant work Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles for a seriously in-depth analysis of this situation.

February 15, 2011 at 10:35 pm

-

Tyrone,

Why “remarkably”?I read his book in two days. I couldn’t put it down.

February 16, 2011 at 12:11 pm

-

The possibility of it not being there isn’t relevant to the conversation, that falls under the discussion of fraud. The account is but a record of what was deposited. Deleting it or altering it doesn’t destroy the ownership of the base asset deposited. It only masks the ownership chain. The ownership remains, the record is what was changed.

Property must fall under the base conservation rules of the universe. Without this concept intact, the concept ceases being property and becomes fantasy. Basic societal rubes cannot be formed around fantasy. It’s the same concept behind many libertarian rejection of laws like slander and the opposition to fractional reserve banking. They’re entirely based in fantasy. IP is fantasy. It doesn’t exist. Harry potter doesnt exist. An invention doesn’t exist. The paper may be manipulated to talk about a British wizard and metal may be formed to fit the description of the invention. But that’s what IP is attempting to do, hold ownership over an abstract description that dies not have form of any kind. It can’t be stolen or altered because it does not exist. And law and policy cannot be forked around that which does not exist.

There is no iPhone, there is only an organization of silicon, glass, titanium, and other materials that fit an abstract description.

February 16, 2011 at 11:02 pm

-

@J. Murray February 16, 2011 at 12:11 pm

“The account is but a record of what was deposited. Deleting it or altering it doesn’t destroy the ownership of the base asset deposited. It only masks the ownership chain. The ownership remains, the record is what was changed.”Are you sure this holds up? You can only own what you can prove you own (non-violent) or defend by any other means (violent).

If the record you have that proves that you own $100 in the bank account suddenly goes missing, how will you prove you own it? In this sense, it is the record that is important, because if you have the record, you can claim and defend your ownership of the $100.

You may hold up the bank with a mask and a gun because you “know” $100 in there belongs to you, but how do you think that would really play out?

Just like green paper is a money substitute, the record that you own money is a substitute. Without the green paper or the record, you are SOL.“It’s the same concept behind many libertarian rejection of laws like slander and the opposition to fractional reserve banking. They’re entirely based in fantasy. IP is fantasy.”

Your use of the concept “fantasy” is interesting. What does that mean? Are you saying that a fantasy is not “something”? Then why do we have a word for it? We interpret “fantasy” a meaning something to do with creation that is not limited by the tangible world. Until we fix our fantasy in some tangible form, it cannot be communicated to others, but the fact that it can must mean there was “something” there to communicate.

“Harry potter doesnt exist.”

He sure made a ton of doe for somebody. Nice fantasy!

“But that’s what IP is attempting to do, hold ownership over an abstract description that dies not have form of any kind.”

I think you are trying to say that the intangible can only exist in the form of some tangible thing, and the tangible thing is all that there is?

Mises wrote about this and Tucker quoted him recently. I can’t recall verbatim but he was talking about the intangible thoughts that precede action, and he said something like, just because they are intangible, they are not phantoms. They are real and affect the world in very specific ways. They are the process of rationalization, for example, that precedes human action. You can only see the action, but it is obvious that that action did not come from nowhere. If you want to know what it is, look at the actions. If you see a production process, that process started as a plan, which is intangible but not a phantom. It exists.

When humans act, their “fantasies” take form. The form cannot exist without the prior existence of rational thought. Just because these thoughts manifest Harry Potter does not make them any less real than the plans to build a forge that can be used to produce a sword.

“It can’t be stolen or altered because it does not exist. And law and policy cannot be forked around that which does not exist.”

Well, you can’t take my “fantasies” directly from my brain. But if I express my fantasies in the form of a story, you can copy that story from the original. If you did that on a scale of production that resulted in very good copies that could not be distinguished from the originals, I would call that counterfeiting. By simply incurring the costs of duplication, you are obtaining the benefit of someone else’s capital investment for a very low cost, just like printing a suitcase of $100 bills for the cost of some paper and ink and spending them like you earned them.

What is the difference in the context of IP or any other form of production?

“There is no iPhone, there is only an organization of silicon, glass, titanium, and other materials that fit an abstract description.”

Case in point. If I put a pile of silicon, class, titanium and other materials on the table, would you be able to produce an iPhone? At any cost, much less $300?

I know you have heard of “I am Pencil”, but did you see the video floating around here, I think it was a TED presentation, called “I am Toaster”? If it was easy, everyone would be doing it. If it is easy (photocopying), that doesn’t make it inherently different. That just makes it a candidate for counterfeiting.

February 15, 2011 at 5:01 pm

-

Why all pro-IP people still assert these kind of analogies when they were refused many times?

February 15, 2011 at 8:38 pm

-

I don’t know, why do so many people laugh when I tell them “taxing is stealing”?

February 15, 2011 at 9:33 pm

-

Taxation is voluntary!! Didn’t you get the memo, brah?

February 16, 2011 at 8:50 pm

-

I think the word you want is ‘refuted’, not refused. I would deny they were adequately refuted.

February 15, 2011 at 5:08 pm

-

Checking accounts arise by express agreement. They are not property, except by metaphor. They are just contractual claims to be paid an amount of money in the future according to certain terms and conditions, and as such are justified by the promise and/or agreement, not by property principles, which are (where valid) applicable to everyone regardless of agreement.

There is no such thing as intangible property, other than that which is built upon agreements, promises, contracts and the like, the rights to which can then be transferred around from person to person as though they were property, although they do not originate in any way comparable to rights in tangible property.

Tangible property is a normative principle arising from a conflict of incompatible uses (sometimes called scarcity, sometimes called rivalry), which is not possible with regard to infinitely replicable patterns.

Perhaps contractual rights (like checking accounts) can be thought of as originating in physical property — i.e., the property rights one has in oneself. Since a man owns himself, he can therefore promise to pay someone X amount of money in the future. Using force to compel performance of that promise is justified, because he had the right to alienate that sum of money from his person by choice. But Imaginary Property doesn’t purport to operate that way, either.

February 15, 2011 at 6:33 pm

-

Phinn,

“They are not property, except by metaphor.”What does this mean? They ARE property by metaphor, or that are not really property, they just act like it?

“There is no such thing as intangible property, other than that which is built upon agreements, promises, contracts and the like, the rights to which can then be transferred around from person to person as though they were property, although they do not originate in any way comparable to rights in tangible property.”

See how hard you work just to avoid actually calling it property? It walks like a duck, talks like a duck, but its really a zepbra?

Property that can arise by contract can be encoded by law. The difference is jsut as you say; laws are universally applicable and do not depend on privity in contract.

“Tangible property is a normative principle arising from a conflict of incompatible uses (sometimes called scarcity, sometimes called rivalry), which is not possible with regard to infinitely replicable patterns.”

Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the tangible, (except contracts, checking accounts, securities, etc. etc. etc.), so IP cannot be property.

“Since a man owns himself, he can therefore promise to pay someone X amount of money in the future. Using force to compel performance of that promise is justified, because he had the right to alienate that sum of money from his person by choice. But Imaginary Property doesn’t purport to operate that way, either.”

A promise to pay creates a property interest in the promisee, which can be sold, assigned, or borrowed against as collaterial. i.e. it is PROPERTY. Therefore it operates EXACTLY like other property. There even a concept of tresspas, it is called “interference with contract”. See???

February 15, 2011 at 6:48 pm

-

>>Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the tangible, (except contracts, checking accounts, securities, etc. etc. etc.), so IP cannot be property.

Wrong. The assumption is that property rights are derived from scarcity. In the realm of ideas and thoughts, there is no scarcity. Hence, there is no legitimate intellectual property that can arise in a free-market. QED

Any attempts at intellectual property would have to be artificially maintained by a coercive monopoly on violence, viz., a government.

February 15, 2011 at 7:13 pm

-

Tyrone Dell,

Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the SCARCE, (except contracts, checking accounts, securities, etc. etc. etc.), so IP cannot be property.

If I copy one contract exactly, do I get twice as much stuff?

If I make a copy of my bank statement, do I have two bank accounts?Why not? I didn’t change the scarcity of the originals?

Ideas are not scarce. What is an idea? “Idea” is an idea. Anyone can use the word any way they wish. Ideas are specifically not protectable by patents or copyrights. Yet original works of authorship are.Does that mean that stories are not simply ideas? Does that mean that a story while having something in common with ideas, are not one and the same thing? A mere interpretation of the same phenomena, (whatever that means)?

If you are a sword maker and you use free oxygen in your furnace, does that mean the sword you produce is free to all takers? I mean, oxygen is free, so how can you claim property rights in the products of your own means of production? Because oxygen comes from the public domain, then everything you produce with oxygen must be free! Yea!!! To each according to their need!! Utopia!

Stories are scarce. If you don’t think so, try to write one. Make it a short one, say 100 pages. But if you use any letters, words, ideas, facts, or knowledge, you must make it a gift to all of humankind. Wonderful…

February 15, 2011 at 8:45 pm

-

“Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the SCARCE”

Scarcity means rivalry, that is there exists conflicting uses of a good (one person’s use of a good at a given time implies no one else is using it at that time). The only reason why property rights exist at all is because of this kind of scarcity. After all, if there was no rivalry there would be no conflict, no disagreement, and no need to establish at all what is “justified” and what is not.

Perhaps what the anti-IP side has failed to illuminate enough is that when we say “there are no property rights in non-scarce (non-rivalrous) goods like ideas” we don’t mean “there shouldn’t be” but rather “there are not”. Nobody is actually concerned with property rights in ideas, which are simply inconceivable. The point is that when people think they are “protecting their ideas” it has nothing to do with the idea but with other *scarce* goods, like bodies, recording devices or productive plants.

People do not have a choice to place property rights in non-scarce goods. There simply is no conceivable form of “rights” in such goods. Some IP supporters have openly admitted this and, I guess, asked “so what?” I guess the best answer to that is, “Well all that property IP grants people rights to, is property whose rights were already granted to someone else through the homesteading principle. It can either be homesteading or IP, not both, and if you give up homesteading you give up your body.”

February 17, 2011 at 11:03 am

-

Very well put sweatervest,

based on my current experience however, IP confusists will however continue to avoid confronting this issue at all costs.

February 17, 2011 at 1:41 pm

-

Sweatervest,

“People do not have a choice to place property rights in non-scarce goods.”

Your error is equivocation. If I agree that property rights are only legitimate for scarce goods, that does not mean that I can equate the non-scarcity of “ideas” with the scarcity of “original works of authorship”. That is like equivocating “words” with “information”, or the letter “a” with “word”.

Do you deny that such works are scarce goods, requiring capital and a means of production?

Furthermore, do you deny that a producer who owns the means of production has a property right in the products thus produced?

February 15, 2011 at 8:52 pm

-

http://academy.mises.org/courses/logic/

You are quite possibly one of the worst cases of sloppy, confused thinking that I have ever come across on the Internet. Congratulations.

P.S. – No, this isn’t an ad hominem.

P.P.S. – Nobody except you ever assumed their conclusion. You are assuming your conclusion that Intellectual Property really is property. You have yet to prove it. See [1] and [2] for more information regarding how to prove propositions.

P.P.P.S. – I highly recommend the book An Introduction to Mathematical Reasoning by Peter J. Eccles. It’ll help you straighten and streamline your thinking so we don’t have to put up with your dull tirades for much longer.[1] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formal_proof

[2] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Axiomatic_systemFebruary 15, 2011 at 9:17 pm

-

Wrong, Tyrone, because very few people bother to think! And, if you read my earlier contribution, you’ll see my justification for a form of IP.

February 15, 2011 at 9:20 pm

-

Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the SCARCE, (except contracts, checking accounts, securities, etc. etc. etc.), so IP cannot be property.

Those things are scarce. If I go to a bank and set up a checking account but never get any paperwork at all from them, how do I challenge in court to prove that I have a checking account with them if they just stick the money in their pocket and act like they’ve never seen me before? You think the property is in the promise but good luck with that in court. I’ve never heard of someone claiming a promise was property.

“If I copy one contract exactly, do I get twice as much stuff?

If I make a copy of my bank statement, do I have two bank accounts?No, you just have created a duplicate of the contract and the bank statement. Do you think that copying a contract or a bank account should be protected by IP law?

February 17, 2011 at 11:31 am

-

Wildberry,

Again, you just assume your conclusion; property is limited to the SCARCE, … , so IP cannot be property.

If this wasn’t true, then it would be trivial to refute it, like I said already on multiple occasions, by showing an example of an action that involves a non-scarce good but does not involve a scarce good. So where’s the refutation?

If on the other hand, such an example is not known of, the claim becomes a falsifiable but not yet falsified proposition. I.e. a proper theory from the point of view of a falsificationist.

February 17, 2011 at 11:52 am

-

Dan, Tyrone, sweatervest, Peter

I’m going to state in advance that admitting this doesn’t mean that there is necssarily any case whatsoever to IP, just in the interests of getting a straight answer. Because, frankly, I’m genuinely curious at whether you are all unable to grasp this, unwilling to grasp it, or simply think this question is irrelevant. (My personal view is Kinsella has brainwashed you all into a weird combo of the second and third).

Let’s agree that action only ever uses tangible stuff. Do you agree that the suitability of some goods, which are being used as means for some end, depends on their scarcity?

If you don’t want to answer that directly for some reason, to expand – do you agree, for example, that in a society where gold coins were the only money, if some alchemist produced gold from sand, then gold would immediately, that day, become unsuitable for use as money.

Yes or no would be sufficient.

February 17, 2011 at 12:05 pm

-

The use of a good is heavily dictated on how scarce it is. If an alchemist did, in fact, find a way to produce gold out of sand, then gold’s valuable use would rapidly expand. Gold is an incredible anti-oxidizer for example. Utilizing gold coating on metal framing in cars, buildings, and other uses of iron and steel would dramatically reduce rusting and improve the lifespan of the structure. Gold also makes a good conductor because of how well it transmits electrons and because of how soft it is, gold would quickly replace copper as the material of choice for electric wiring in homes, buildings, and high tension lines.

As for the increasing amount of gold on the money supply, gold would end up being supplanted by something less likely to be produced in such high numbers to function as money.

And there would be nothing wrong with the above. Gold has valuable industrial uses that aren’t readily explored because of the metal’s scarcity. Money is, in the grand scheme of things, one of the least important uses of physical goods. Replacing gold with some other commodity that has similar produtctive uselessness as gold does now wouldn’t negatively harm the system whatsoever. Pricing would just refluctuate around the new unit of measurement and it’s new relative scarcity.

February 17, 2011 at 2:30 pm

-

“Gold is an incredible anti-oxidizer for example. Utilizing gold coating on metal framing in cars, buildings, and other uses of iron and steel would dramatically reduce rusting and improve the lifespan of the structure. Gold also makes a good conductor because of how well it transmits electrons and because of how soft it is, gold would quickly replace copper as the material of choice for electric wiring in homes, buildings, and high tension lines.”

You’re winding me up right? What has this got to do with the point at hand? I’m convinced you don’t even read some of the posts you respond to.

I asked a very specific question. You didn’t answer it. Or, if you did, it was lost in your seemingly uncontrollable desire to take this as an opportunity to lecture everyone on points that are utterly irrelevant.

February 17, 2011 at 12:54 pm

-

Hi Kid Salami,

I’m going to state in advance that admitting this doesn’t mean that there is necssarily any case whatsoever to IP, just in the interests of getting a straight answer.

Even if that was, I would have no problem with that. I didn’t say there is no case whatsoever for IP, but that the theories as they are presented by IP proponents are, well, you know, crap. That does not mean that they can’t fix it.

Do you agree that the suitability of some goods, which are being used as means for some end, depends on their scarcity?

Yes. Scarcity influences the opportunity costs of actions, so it’s kind of obvious. Of course, there are other factors that influence usability too, for example the scarcity of substitutes.

in a society where gold coins were the only money, if some alchemist produced gold from sand, then gold would immediately, that day, become unsuitable for use as money.

Ceteris paribus, I agree. I have actually been hypothesising if non-commodity market-produced money (like bitcoin) would replace commodity money if we had replicators (like in Star Trek). But I suppose that’s getting too far ahead of the debate.

February 17, 2011 at 2:33 pm

-

“Yes. Scarcity influences the opportunity costs of actions, so it’s kind of obvious.”

Ok.

February 17, 2011 at 2:34 pm

-

“Yes. Scarcity influences the opportunity costs of actions, so it’s kind of obvious.”

Ok.

“Of course, there are other factors that influence usability too, for example the scarcity of substitutes.”

What, exactly, do you mean by this?

February 18, 2011 at 1:44 pm

-

Kid Salami,

What, exactly, do you mean by this?

Strictly speaking, it does not have to do directly with your question, so please accept my apologies. My intention was not to divert attention, but to point out that the sentence is an implication rather than equivalence (the implication does not work the other way around).

February 15, 2011 at 7:05 pm

-

Wildberry, you are hopelessly confused. You said all you needed to say when you argued that slavery is justified if enough people think it is.

This is what you reallyean by “human device” — that any unprincipled nonsense can stand if we only believe it makes sense.

Morality must be founded on principle, or it is merely a lie — an instrument of oppression. There is nothing more effective in subjugating humans than false assertions of morality.

You are a hypocrite every single time you trot out the “human device” line. You assert moral principle by merely making a claim of property, but then contradict yourself by arguing that moral rules can be whatever “we” want them to be.

No, they can’t. If they can be whatever we want them to be, they are not a matter of principle. In which case, it’s only your opinion that you’ve asserted, which is worth nothing.

Slavery can’t be both ethical and unethical, depending on who is announcing the human device du jour. Either the principle is that it’s wrong, or that it’s not.

“Human device” is a euphemism for “preference.”. I don’t give a fig what your preferences are. If instead you are going to claim to know what is right and just for all humanity, then you are required to elucidate the universal moral principle at work. You haven’t and you can’t.

February 15, 2011 at 7:50 pm

-

@ Phinn February 15, 2011 at 7:05 pm

“You said all you needed to say when you argued that slavery is justified if enough people think it is.”

Now don’t get all righteous on me, Phinn! What I said was: “Even slaves can be called property if we decided to do it. Our common objection is why it doesn’t exist today. It violates our contemporary ethics because we hold that a superior principle of liberty trumps it.”

We did (historically speaking) decide to do it, and then we decided not to do it. It is wrong not because the concept of property is “wrong”, but because attributing property rights in other humans is wrong. Both were decisions made by people and enforced on other people. That is the way property works, no? It worked the same during and after slavery, yes? I’m talking about property rights, not slavery. I think you jumped the gun, but I’ll give you another chance.

“This is what you reallyean by “human device” — that any unprincipled nonsense can stand if we only believe it makes sense.”

Is this not the case? So what do we really believe? That’s what matters. Beliefs have a way of manifesting themselves in society, don’t you think? The trick is to believe in good and right stuff, right? It hasn’t always been that easy.“Morality must be founded on principle, or it is merely a lie — an instrument of oppression. There is nothing more effective in subjugating humans than false assertions of morality.”

Not sure what you’re getting at here, but it sounds really righteous. Morality is simply a measure of how we conduct ourselves compared to toe prevailing principles of ethics. Getting the ethics right is the history of human struggle. Are we still talking about the ethics of recognizing property rights in the intangible works of authorship?

“You are a hypocrite every single time you trot out the “human device” line. You assert moral principle by merely making a claim of property, but then contradict yourself by arguing that moral rules can be whatever “we” want them to be.”

As distastefully as it may be, that is exactly what morals are. Not YOUR morals, or MY morals, but morals in general. Ubangi cannibals may have a different code of ethics than me, but they still operate within a code of ethics. They still judge each other as committing moral and immoral acts. That’s what human societies do. Our society has its own morals, and they are based on the principles we hold. Are we still talking about IP?

“No, they can’t. If they can be whatever we want them to be, they are not a matter of principle. In which case, it’s only your opinion that you’ve asserted, which is worth nothing.”

I like to think my opinion is not worth nothing, but you have cast your vote, so I’ll have to live with that. Another opinion I have is that you and I probably share many ethical principles, but you want to generalize that I’m a slave monger, or that I have no principles, or whatever, just because we disagree on the principles of the ethics of property relative to IP. Let’s dial it back a few notches, eh?

“Slavery can’t be both ethical and unethical, depending on who is announcing the human device du jour. Either the principle is that it’s wrong, or that it’s not”

Just to be clear, I am certain that my code of ethics calls slavery unethical. It is wrong because it violates the golden rule, among other things. We no doubt agree about that. But in the end it is just an opinion, but one backed up by some strong principles and sound logic. That one is a settled issue, in my mind. But even today, not everyone and not everywhere do humans act morally based on our principles. We should keep after it. Are we still talking about IP?

“Human device” is a euphemism for “preference.”

It is. We can be said to prefer one code of ethics over another. Take any two people, say Phinn and Wildberry, and line their principles up. Some of them will align, like on slavery, and others will not, like IP. That doesn’t make you a bad person, Phinn. You’ll eventually catch on.

“I don’t give a fig what your preferences are.”

No kidding?

“If instead you are going to claim to know what is right and just for all humanity, then you are required to elucidate the universal moral principle at work. You haven’t and you can’t.”

Well, I didn’t presume to be the second coming, so your challenge is a little above my pay grade. However, if we are still talking about IP, I am saying that you and others who oppose the very concept of IP are inconsistent and/or dishonest in your analysis of property rights, what they are and where they come from. You have adopted a single standard test that you try to apply universally across all of creation, and when you encounter inconsistencies, you just define them away and act like you have discovered some kind of moral high ground.

Let your conclusions rest a minute, and you can see that there’s plenty of room around here for differing viewpoints. At the moment, you reside in an ethical position that is not very universal. Your world view is at odds with most of humanity. Certainly you are at odds with the prevailing system of ethics, morality and laws. So I would say you have a tall hill to climb before the rest of us can see your light. Be patient with us.

February 15, 2011 at 9:11 pm

-

You have adopted a single standard test that you try to apply universally across all of creation …

So has everyone who has ever uttered any phrase along the lines of “You should …”

That’s what all normative assertions pretend to be — an assertion of universal application. Otherwise, it’s really nothing more than an assertion of “I’d prefer it if you did …” Which is fine, I guess, but means nothing in terms of ethics, or certainly carries no more weight than anyone else’s expression of preference. People often try to avoid that obvious insignificance by pretending their preferences are assertions of universal principle.

You want to pretend that your normative assertions are both a “human device” (and thus vary from tribe to tribe, person to person, time to time and culture to culture) and a declaration of universal principle.

Let your conclusions rest a minute, and you can see that there’s plenty of room around here for differing viewpoints.

They’re not viewpoints. They’re assertions of principle. To the extent they differ, either one is right and one is wrong, or both are wrong. Inconsistent assertions of universal principle cannot both be right.

Your self-contradiction and hypocrisy is childish and patently silly.

Your world view is at odds with most of humanity.

So? That makes people right? Popularity?

February 15, 2011 at 9:34 pm

-

“So? That makes people right? Popularity?”

I’ve been very surprised at how many people I’ve talked to conceive of ethics as some sort of prior agreement to be reached by as many people as possible on what the rules should be.

My response is, “If that ever happened there’d be no need for ethics”.

February 15, 2011 at 9:56 pm

-

Some people are VERY uncomfortable with the idea of universality in ethics. But ethics IS universality. That’s what it is. That’s what it claims to be. Otherwise, it’s just your preference against my preference, and for me, my preference wins every time. Same for you, I suspect.

These people are uncomfortable for two main reasons, in my experience:

A. They’re morally corrupt. They deny universality of principle because they are on the wrong side of universal principles, the way that bank robbers deny that they robbed a bank. Corrupt people love to confuse, obfuscate and change rules. The really smart ones become politicians.

B. They are moral relativists, like Wildberry. This denial of universality is clearly a psychological defense mechanism. I have never met someone who exhibits such a trait who did not grow up with an abusive, domineering parent. This abuse invariably takes a very distinctive form — a specific kind of dogmatic, doctrinal domination. The parent imposes some set of irrational beliefs on the child, which the child (being more rational) rejects, but is not allowed to express his rational argument. The child who grows up with a parent who put him in that kind of mental prison finds only one escape — he retreats into the belief that all doctrinal assertions are relative! Meaningless! It’s all a game! There is no universal truth!

People who reflexively balk at universality and ethical certainty, and work so hard to deny universality in matters of ethics, might as well hang a sign on their chests that say, “I had an irrational, overbearing, dogmatic parent.”

February 16, 2011 at 11:05 am

-

“I have never met someone who exhibits such a trait who did not grow up with an abusive, domineering parent.”

What about twelve solid years of state “schooling”?

It was there that I was conditioned into moral relativism. In that situation I think the chance of having an oppressive parent becomes the guarantee of having an oppressive teacher (by “teacher” I of course mean a prison guard charged with the duty of brainwashing), and what better way to abandon one’s sense of right and wrong to have to deal with maniacal classroom managers every day? Especially when the highest priority of all teachers (not personally but as described by the job) is to relentlessly crush any deviation from the dull conformity that is so praised in schools (if only because it makes running a school that much easier).

I actually reached a conclusion very similar to yours here. My school administration was particularly keen on constructing arbitrary, shifting and blatantly silly “demerit” systems punishable by detention, and this made it nearly impossible to have respect for any system of rules (if only they knew what part they hard in pushing me towards anarchism!). In particular, I remember that “disrespect to an authority figure” was a more serious offense than “skipping class” or “driving recklessly on campus”. By witnessing this it was only expected, I think, that I decided that all systems of rules are totally arbitrary and only satisfy the whims of those writing the rules.

Of course when you start pretending that you know universally valid things about the world (like, I don’t know, 2 + 2 = 4) you often find people who accuse you of being an “ego maniac” that doesn’t want to acknowledge his own fallibility. The irony is that the one claiming to be infallible is the one claiming there is no truth and thus I can say whatever I want and no one can tell me I’m wrong! Maybe this plays into the whole relativism resulting from oppressive “rulers” in one’s life.

I actually believe that all discrepancies in scientific theories, not just limited to ones in a political context, come ultimately from a disagreement in one’s theory of knowledge, i.e. epistemology. From what I have noticed the people with whom I agree most consistently are the ones that share my rationalist epistemology. The ones who disagree are usually empiricists or historicists.

This intellectual property issue cannot avoid become highly philosophical and as long as there is disagreement over epistemology there will be disagreement over what is property and what is not.

February 16, 2011 at 12:08 pm

-

What about twelve solid years of state “schooling”?

Sure! But school is really just a proxy for parents. The emotional trauma to the child arises from the fact that the parents sub-contract the abuse out to these strangers. They tolerate it, support it, promote it.

Whenever irrational moral certainty is used as a weapon against you (particularly when you are in the dependent state of childhood), the common reaction is to learn to reject moral certainty. That’s the only defense that’s available, sometimes.

Of course, the problem all along was never the moral certainty, but the irrationality — the problem was the moral error of the people who engaged in this systematic abuse (parents, teachers, etc.).

Moral certainty, in and of itself, is nothing to be afraid of. But I can see why some people develop an allergic reaction to it. In fact, it can be quite healthy, in the long run, but it can be frightening. It is an often overwhelming prospect to consider the fact that you were systematically abused for the first 20 years of your life by people who claimed to love you, and that it was all for your own good.

When moral certainty reveals that this treatment was monstrous, it tends to make Thanksgiving dinners somewhat awkward. It’s often easier to be a moral relativist than to face the burden of emotional trauma, or to call evil by its proper name.

February 15, 2011 at 7:09 pm

-

I’ll try once again, though many of the contestants here seem set in their ways.

I stand for Common Intellectual property. I am a minarchist, not an anarchist. I think that the roads, and public spaces not privately owned, should be owned and run by local democratic counties or shires. As owners of the commons, they can licence what goes on in the Common property. This is what copyright and patents could become- licences to use and advertise over common property. If I claim a patent for something I might call The Binary Button, something to replace ordinary buttons, I would be able to advertise on radio and TV, and the counties would use my product. Nothing would stop you developing your own version, and relying on word of mouth to get your version publicity. nobody would interfere with your private property in any way!

I think of this as a middle way between the two arguments, as neither anarchy nor centralism seem like good alternatives.February 15, 2011 at 9:22 pm

-

You should check out Hans-Hermann Hoppe’s Democracy: The God That Failed.

1. http://www.lewrockwell.com/hoppe/hoppe4.html

2. http://mises.org/store/Democracy-The-God-That-Failed-P240.aspx

3. http://www.amazon.com/Democracy-Economics-Politics-Monarchy-Natural/dp/0765808684/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1297822961&sr=8-1February 15, 2011 at 10:44 pm

-

None of that will prove that Anarchy will work!

February 16, 2011 at 12:28 am

February 16, 2011 at 12:34 am

-

It may be true that there will always be a coercive government, just as it may be true that there will always be murder. But advocating for some state violence (as you do as a “minarchist”) is no more justified than advocating for some murder.

February 16, 2011 at 1:05 am

-

However, advocating that property-owners have rights, as I do for local counties, is entirely consistent with libertarianism! I also believe that counties should be at least democratic, though I would prefer that all citizens have a time-share role in local government (for one month of the year, you and 1/12th of all people who chose to be citizens would have the right to pass or repeal any and all laws, which would only affect the non-private properties within the county).

I reject your claim that I advocate violence! Just as any property-owner can (or should be able to) control what happens on and within his/her owned properties. This is never called violence if the wishes of owners are enforced. February 16, 2011 at 5:21 am

-

Some murder is a good thing. Like preventive killing of people who are about to kill you or steal from you or your family. Here it is not a vengeance or a punishment, but a prevention. That is when trespasser is retreating, or is subdued, then killing him would be a bad murder, similar to that of shooting random people in the streets.

February 16, 2011 at 11:10 am

-

“Some murder is a good thing.”

Yes, responding to violence with violence is not unjustified. Only initiation of violence is unjustified.

The state is definitely an initiator of violence, and so if you lend some support to the state you are not just saying “some violence is okay”, you are saying “some initiation of violence is okay”, which is no less than a complete compromise of ethics.

February 16, 2011 at 1:37 pm

February 16, 2011 at 11:08 am

-

“None of that will prove that Anarchy will work!”

Nothing you can say or cite would prove that anarchy will not work (as in work far better than governments).

February 16, 2011 at 6:53 pm

-

Not true! Somalia is an anarchy, and nobody seems to want to move to this new anarchic paradise! I think a government would improve the place, as in, people would be happy to move there! (And wouldn’t that be the ultimate proof that a society is successful?)

February 16, 2011 at 7:56 pm

-

That is hillarious! This is why John Stewart is so popular. Nothing makes a point better than humor. Well done!

February 16, 2011 at 9:02 pm

-

Somalia isn’t anarchy. It’s groups competing to be government, also known as war. The problem with Somalia is there is way too much government that it can’t function at all.

February 16, 2011 at 10:41 pm

-

A few facts:

1. Somalia is a sh*ithole because of 25 years of hard-core Marxism.

2. Ever since the State there collapsed, quality of life there improved in virtually every measurable statistic, especially things like infant mortality.

3. The great prize for the warlords that continue to plague the people there is to be recognized as the Kingpin Warlord by the Kingpin of All Kingpin Warlords — the US government. Without that incentive, fewer Somali children would be dead.

Economics is about understanding cause and effect. You don’t seem to do that.

February 16, 2011 at 11:20 pm

-

Watch this video by Ben Powell titled “Statless in Somalia”: http://fee.org/media/video/stateless-in-somalia/

February 15, 2011 at 7:30 pm

-

Contract is not property, it is an agreement or claim by one individual on another to perform (or not perform) some said act. A “written contract” is merely this agreement put on paper and thus embodies the agreement between person A and person B. Its a physical way of showing that such and such agreement was made. It is a form of law, not something which is own-able by any person.

Also to the claim that these claims can be sold as a contract and thus property is not correct either. If I made a contract that guaranteed you will get an orange, then by that agreed contract you should get that orange. However, if you do not, then you were frauded out of your orange and thus had your money stolen from you. The claim is merely an agreement, it is not actual property. To put another way, let’s say I give you100 dollars to fix my bathroom and you don’t. Then you committed fraud against me as it wasn’t your yes that I wanted, but my bathroom to be fixed. No “written” contract was made, but it is obvious I did not pay for your agreement, I paid for your services. The last example I can think of is paying someone to keep their mouth shut. What I am actually paying for is the person not to talk (a service), not his agreement to keep silent. If he breaks that agreement, then he has committed fraud against me. Contracts, whether written or not, are thus not property.

The issue with IP is that no such contract was made between the copier and the clement of the IP law. When I buy a book, I have no signature telling the person that I will agree not to copy the content of this book and post it on the Internet. If IP laws were truly valid, then such acts as letting someone borrow the book should be illegal as it is no different r from the basic premises embodied in all IP arguments. The reasoning is that people will not buy the said book if I let someone else see it for free. However, that person did not pay for the privilege in the first place and thus “stole” the money which should have gone to the author according to pro-IP ideas.

Same goes with music. If I pay for a copy of music, but I let other people hear it and even give away the CD, then I should technically be in violation of IP laws as stated by those who believe in IP. Its not the CD I gave the person, but the content which he or she should have paid for. Other people who listen to the music are getting a “free” show as well and should also be, under your justification, the confines of IP. This can go on and on.

As for a checking account, those digits are not the physical money, but a claim on the physical paper money. The reason it is forgery form me to add those digits to my account is simply i am lying about how much real money I have in the account and I am thus stealing from others pile of money. This is why Fractional reserve and fiat banking is unethical since the bank hands out false claims on other people’s money. Once again, a claim is a matter of law not a form of property.

February 15, 2011 at 8:04 pm

-

@Michael Richards February 15, 2011 at 7:30 pm

I don’t have time to explain in detail, but your concept of contracts is limited.

Whereas a contract may be for any number of things, it is basically a promise for a promise to do or abstain for doing some act.

A contract that promises performance, say to transfer a bushel of oranges in two weeks, becomes a security interest in a futures contract for a bushel of oranges, and can be traded as property without every taking possession of actual oranges.

There are the tangible oranges, and the intangible security interest. Both are actually property, literally. You can describe a distinction between oranges and a security interest in them, but they are both property in every sense.

This common sense concept of property is rejected by many here who believe that property can ONLY be in scarce goods, and only tangible goods are scarce. By this logic they would have to conclude that the security interest is something other than property.

I say, if it walks like a duck and sounds like a duck, it’s probably a duck.

February 15, 2011 at 8:49 pm

-

“Whereas a contract may be for any number of things, it is basically a promise for a promise to do or abstain for doing some act.”

This is too vague. A contract is a bi-directional conditional exchange of property. A grants use of A’s property to B on certain conditions, one of which being that B grant A use of some of B’s property, and B does the same. Thus a violation of the conditions by either party constitutes a trespass on the exchanged property of the other party, which is a mere extension of both party’s already existing rights in their property.

February 16, 2011 at 2:28 am

-