See: How to Improve Patent, Copyright, and Trademark Law

An Open Letter to Congress

Dear Member of Congress:

Below please find some suggestions for legislative improvements to federal law in favor of American free markets, property rights, and individual liberty.

A little bit about me and my areas of specialization. I am an attorney in Houston. I have practiced intellectual property and patent law for over 28 years, and have also spoken and written in favor of private property rights and free markets, and against the existing intellectual property system, including patent and copyright law, over the same period. I am licensed to practice law in Texas, Louisiana (inactive), and Pennsylvania (inactive), and registered to practice before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (Reg. no. 37,657). I have B.S. and M.S. degrees in electrical engineering (1987, 1990), and a J.D. (1991), from Louisiana State University, and an LL.M. from King’s College London–University of London (1992). I was a partner in the Intellectual Property Department of the national law firm Duane Morris, in Philadelphia and Houston, general counsel for the high-tech laser manufacturer Applied Optoelectronics, Inc., and am now in private practice in Houston. I have prosecuted hundreds of patents for a large number of companies, including Intel, General Electric, UPS, and others. I’ve also published widely on legal topics from international law to IP law (my most recent legal publication is International Investment, Political Risk, and Dispute Resolution (Oxford University Press, 2020)) and on legal theory and policy, including my best-known work, Against Intellectual Property (Mises Institute, 2001/2008). I have also helped to draft proposed legislation on a number of occasions, including a bill proposed to the UK Parliament to help return to sound money (see my post UK Proposal for Banking Reform: Fractional-Reserve Banking versus Deposits and Loans).

One of my main areas of research and writing has been on the harm done by IP law to private property rights, free market competition, innovation, civil liberties, and freedom of speech and the press. It is my considered view that copyright law, in particular, threatens these civil liberties, and freedom on the Internet, and heavily distorts culture. In addition to my research, writing, speaking and debating on this issue, I also I conducted a six-week Mises Academy lecture series on the dangers IP law poses to America’s free market system (see “Rethinking Intellectual Property: History, Theory, and Economics: Lecture 1: History and Law” (Mises Academy, 2011). In addition to Against Intellectual Property and other writings on IP policy issues, I’ve also published on purely legal aspects of IP law, such as Trademark Practice and Forms (editor; Oxford/Thomson Reuters, 1998-2010).

My suggestion is that you should consider proposing legislation that would recognize the tension between copyright, which limits freedom of speech and the press, and the First Amendment, which protects these rights, and readjust the balance in favor of civil liberties and property rights.

There is no question that copyright, in its modern form, significantly distorts culture and restricts freedom of speech and freedom of the press, and also threatens freedom on the Internet. For just a few examples out of a depressingly large number:

- The young Internet pioneer Aaron Swartz, who helped develop the RSS technology that underlies blogging and podcasting, as well as the Markdown publishing format and the organization Creative Commons, faced with a possible 35-year federal prison sentence and over $1,000,000 in fines for uploading academic articles to the Internet, committed suicide in 2013, at the age of 26.

- British graduate student Richard O’Dwyer faced extradition to the US to face federal criminal charges merely for having a website with links to pirated movies.

- Shortly before his death, author J.D. Salinger, author of Catcher in the Rye, convinced U.S. federal courts to ban the publication of a novel called 60 Years Later: Coming Through the Rye.”

- The seminal German silent film “Nosferatu” was deemed a derivative work of “Dracula” and courts ordered all copies destroyed.

- In Canada, when a grocery store in Canada mistakenly sold 14 copies of a new Harry Potter book a few days before its official release, a judge “ordered customers not to talk about the book, copy it, sell it or even read it before it is officially released at 12:01 a.m. July 16.″

- The Stop Online Piracy Act, or SOPA, which threatened freedom on the Internet, was narrowly defeated in 2012, but its provisions keep coming bad in other guises.

- To-wit, the recent Covid-19 Relief Bill attempted to make illegal online streaming a federal felony, and also provided funds “for the maintenance of an ‘International Copyright Institute’ in the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress for the purpose of training nationals of developing countries in intellectual property laws and policies”.

- The copyright “safe harbor” provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which helped provide a legal framework that allowed the modern Internet to thrive and flourish (blogging, commenting, Youtube, etc.) are under siege at this moment from advocates of copyright.

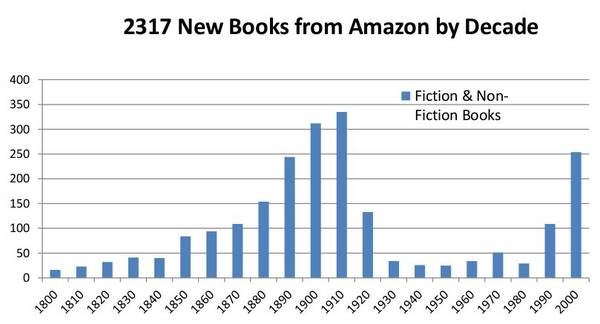

- There is an ominous 80-year “black hole”–most of the Twentieth Century–of potentially lost literature due to long copyright terms and the “orphan works” problem that results from the abolition of copyright registration formalities since accession to the Berne Convention in 1989: see my post How long copyright terms make art disappear — see graphic below:

For further information about the censorship roots of copyright, see Karl Fogel, The Surprising History of Copyright and The Promise of a Post-Copyright World.

A good case can be made that the Copyright Act, in its modern form, is unconstitutional, since it violates freedom of the press and speech, protected by the First Amendment. The Copyright Act is based on the Copyright Clause in the Constitution, Article I, Section 8, Clause 8, which provides:

“[the United States Congress shall have power] To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

(Somewhat contrary to modern usage, “Science” at the time referred to writings, “knowledge,” and so on, and thus to the copyright grant; whereas “useful Arts” refers to machines and inventions, i.e. the designs of “artisans”.)

There are several reasons why the current Copyright Act is arguably unconstitutional, and clearly violates the spirit of the First Amendment:

First, copyright is clearly a form of censorship, as illustrated in some of the examples given above. The Supreme Court recognized this in a recent copyright decision, Golan v. Holder (2012) (which authorized Congress to restore copyright to works that had fallen into the public domain): “Concerning the First Amendment, we recognized that some restriction on expression is the inherent and intended effect of every grant of copyright.” Thus, there is said to be a “tension” between copyright and the First Amendment.

The Court has tried to reconcile these competing interests by a “balancing” test, as it does in other contexts where there is an incompatibility or “tension” in the law (for example, between the Patent Act and Copyright Act, which grant monopolies, and the antitrust laws, which prohibit monopolization; and between copyright and defamation law).

However, the Copyright Act is based on the Copyright Clause, which appeared in the original text of the Constitution ratified in 1789. The Bill of Rights was ratified later, in 1791. Thus, based upon standard principles of statutory and constitutional construction, where a later statute or constitutional Amendment supersedes earlier provisions, if there is a conflict between copyright and the First Amendment, the First Amendment must prevail. (Just as the 18th Amendment, ratified in 1919 (Prohibition of alcohol), was repealed by the 21st Amendment ratified in 1933.) In other words, instead of trying to “balance” irreconcilable provisions, the Court should have declared the Copyright Act to be unconstitutional. That is, the First Amendment in effect repealed the copyright clause.

The Court sidesteps this argument by saying that “Copyright Clause and the First Amendment were adopted close in time,” (Golan, quoting Eldred, 537 U. S., at 219), and thus tries to find a balance between them or even argue that one purpose of copyright is to promote freedom of expression by providing “a marketable right to the use of one’s expression,” thus supplying “the economic incentive to create and disseminate ideas.” However, this argument is unsound since the Bill of Rights was ratified by a different Congress, two years after the Constitution was ratified.

Moreover, it is important to note that the original copyright law only protected works for 14 years, extendable one time for another 14 years, and provided no criminal penalties. It also required active registration for copyright protection. Today’s copyright law has expanded in scope (it now covers works other than “writings”), term (the term is now life of the author plus 70 years, well over a century in most cases), and criminal penalties instead of merely civil penalties. To the extent the Copyright Act now goes beyond the initial terms of the “Founders’ Copyright,” it should be considered to be unconstitutional. The “balancing” test should be decided in favor of freedom of speech and the press.

For further discussion on the “Founders’ Copyright,” see Intellectual Privilege Copyright, Common Law, and the Common Good, by law professor Tom Bell. As Professor Bell explains,

“Not long ago, in “Five Reforms for Copyright” (chapter 7 of Copyright Unbalanced: From Incentive to Excess, published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in 2012), I suggested that the United States should return to the kind of copyright the Founders supported: the one they created in their 1790 Copyright Act. The Founders’ copyright had a term of only fourteen years with the option to renew for another fourteen. It conditioned copyright on the satisfaction of strict statutory formalities and covered only maps, charts, and books. The Founders’ copyright protected only against unauthorized reproductions and offered only two remedies—statutory damages and the destruction of infringing works.

Second, the Copyright Clause only authorized Congress to protect authors’ “writings,” to-wit: maps, charts, and books. Copyright now covers a variety of other types of works not authorized in the Copyright Clause, such as software, audio-visual works (music, movies), sculptures, paintings, photographs, “boat hull designs,” and so on. To the extent the Copyright Act covers works other than authors’ writings, it should be deemed unconstitutional or, at least, far beyond the scope of copyright initially envisioned by the Founders and thought to be compatible with the First Amendment.

Third, in imposing criminal penalties and indeed, civil penalties unrelated to actual damages–the “statutory damages” of up to $30k per infringing act or $150k if willful, per Section 504 of the Copyright Act, with no showing of actual damages. This is arguably in violation of the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on excessive fines. Statutory damages for copyright infringement should be deemed to be unconstitutional, as a violation of both the First and Eighth Amendments, and arguably also the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Fourth, until the accession to the Berne Convention in 1989, authors had to actively register a copyright and put a copyright notice on the work to receive protection. This limited the number of copyrights granted and also put the public on notice as to what was copyrighted and whom to contact to receive a license. Since Berne, these “formalities” were removed and copyright protection is now automatic, leading to a huge proliferation of the number of works covered by copyright and massive confusion about who the owner is. This has led to the “orphan works” problem and other problems. The removal of formalities should be repealed and copyright should be valid only if and to the extent authors actively apply for a copyright by the registration process, and provide a copyright notice, as in the pre-1989 law.

In view of these comments, I suggest that you propose legislation, which could be styled something like “The First Amendment Defense Act of 2021,” which recognizes the tension between copyright law and the First Amendment and Bill of Rights, and how much worse the tension has become since copyright has expanded from the original “Founder’s Copyright” to the modern system. The bill could propose legislatively amending the Copyright Act to: reduce the term back to the original 14+14 year term, reduce the scope to cover writings only, eliminate criminal penalties, and require copyright registration and notice. Or, at the very least, some kind of legislative statement could be made that recognizes the tension between copyright and the values in the Bill of Rights, and that when these competing values come into conflict, preference should be given, where at all possible–from the judiciary in interpreting the Copyright Act, regulatory agencies, the Congress, and the Executive branch in enforcing copyright–to the First Amendment and freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

I would be happy to provide further links to the facts mentioned above, or to discuss this matter further or provide any other assistance with research, analysis, or drafting of legislation.

Sincerely,

Stephan Kinsella

You must log in to post a comment. Log in now.